HOW THE BANK OF ENGLAND BROKE THE GOLD STANDARD IN AN EFFORT TO SAVE IT

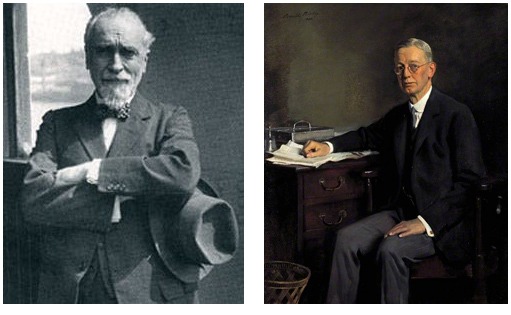

Montague Norman Ernest Harvey

Considering what a fateful development departure from the gold standard was, and what a shocking reversal of the very reasons for the formation of the National Government, Skidelsky, in his book on the slump (p.422), treats it rather breezily:

'The National Government failed to achieve the specific object for which it had been formed. Credits of £89m had been obtained on 28 August [from the USA and the Banque de France - PB]; on 8 September Snowden introduced emergency measures of extra taxation and economies designed to balance the budget by 1933. But a mutiny of naval ratings at Invergordon on 16 September destroyed the confidence temporarily created; the flight from the pound could not be stemmed and on 21 September Britain was forced off the gold standard.'

A much more entertaining account is given by Morrison (pp.192-7):

'The standard narrative is that "Britain was forced to suspend convertibility on September 19." But it was not "Britain" that suspended convertibility - it was, essentially, the Bank of England. And the Bank was not "forced" but chose to do so. This choice was the final manoeuvre in a campaign Harvey waged to save conservatives in Parliament from electoral defeat. Harvey, simply put, suspended the gold standard to save it.'

'Harvey' was Ernest Harvey, Deputy Governor of the Bank of England. Over the Summer the Governor, Montagu Norman, had been incapacitated by illness. In August he travelled to Canada - in fact to negotiate a loan from the Federal Reserve in New York, a project that had to be concealed from the press since it indicated lack of confidence in the pound. Norman was pressing for a radical increase in the bank rate of interest which would have imposed an even tighter constraint on the money supply and on the government's ability to spend. MacDonald believed that his abandonment of the Labour Party and formation of the National Government with a view to saving the pound needed to be ratified by a fresh election.

'Harvey feared the effect of Norman's return on the ensuing election. He knew that Norman would insist on raising Bank rate ruthlessly. Harvey assumed this would provoke a backlash against the gold standard. Suspending convertibility in that circumstance would irreparably damage the credibility of Britain's commitment to the gold standard.

'Harvey thus implored the government "to announce ... that in view of the National Emergency a General Election is not contemplated at the present time." Although the credits might last a fortnight, "It would be impossible with existing resources to maintain the Gold Standard during the period necessary to conduct a General Election." On 18 September, however, MacDonald resolved to hold an election in October.

'Harvey concluded (incorrectly) that this decision made the suspension of the gold standard inevitable. It was only a question of whether the suspension occurred before or after the election - and who was in power at the time. Assuming (incorrectly) that an October election would deliver Parliament to the radicals, Harvey decided to orchestrate a "temporary" suspension while the gold standard coalition still controlled the government. Such a sudden suspension, Harvey calculated, would force the politicians to postpone the election. This would buy time, "giv[ing] the British government opportunity to turn around ... its internal affairs." After resolving the fiscal crisis, the (Conservative-controlled) coalition government could then restore the gold standard and hold the election when Britain had returned to a more conservative mood.

'That afternoon, 18 September, the Bank elected to initiate the suspension of the gold standard. It shockingly resolved to allow gold to fall below the export point. This decision not only violated the understanding established with the Bank of France it also gave the illusion that the credits had been exhausted, which accelerated sterling sales.'

Norman on his return was furious at what his deputy had done but nonetheless it was thought politic to go along with the fiction - according to Morrison maintained by all subsequent historians - that Britain had been 'forced' off the gold standard by the panic selling of sterling on the international market which, it must be said, was certainly taking place. However:

'Suspension did not ensure the gold standard's demise. After all, convertibility had been restored after the wartime suspension. The London Times even reported, "the suspension provided for in the Bill ... is limited to a period of six months." What made things different this time?

'"There are few Englishmen who do not rejoice at the breaking of our gold fetters," Keynes wrote one week after the suspension. Following Keynes, [economic historians] Eichengreen and Temin argue that democracy triumphed over the gold standard: "The world economy did not ... recover when [political and economic leaders] changed their minds; rather, recovery began when mass politics ... removed them from office."

'The opposite was true in Britain. The general election came one month after the suspension. It was "clear during the campaign," the Times reported, that the currency question was "the only issue." Leading Conservative Stanley Baldwin framed it as the "acid test of democracy." Defying Harvey's cynical expectations, Britons rose to the challenge, granting the National Government the largest electoral mandate in modern British history. Pledging currency stability, the Conservatives won 470 seats. Labour, which forswore a commitment "to force sterling back to the old gold parity," lost 215 of its 267 seats. Here, "mass politics" overwhelmingly endorsed "gold-standard ideology." The "cultural hegemony of economic orthodoxy" was displaced only after an unexpected experiment established new ideas.

'Financial markets had reacted to Harvey's surprising announcement "with comparative calm." Hesitant to resume convertibility prematurely, the Treasury recommended "a waiting policy" to "allow sterling to settle at whatever level circumstances suggest is most appropriate." In the first week, sterling slid from the fixed rate of $4.86 to $3.40. The government then proposed a managed float: "the Bank of England should as a provisional policy endeavour to keep sterling within certain limits, by buying sterling at the lower limit and selling foreign currencies at the higher." This worked better than expected, and the Treasury were pleasantly surprised at their ability to "save the pound from the danger to which ... other currencies, similarly situated, have succumbed." After falling to a nadir of $3.23 the pound stabilised within a band between $3.40 and $3.80. The suspension was nothing like the "very great disaster" predicted by these same officials. They had no choice but to update their beliefs. As a chagrined Norman subsequently put it, "We have fallen over the precipice ... but we are alive at the bottom."

'The decision to forestall a return to gold created space for the Treasury to experiment with new ideas about "the role of the exchange rate in the regulation of the economy." As the Treasury investigated the possibilities, it became clear that no one had done more to develop the alternatives than Keynes. In October, his staunch critic in the Treasury - Frederick Leith-Ross - reached out to him. When Keynes's push to remake the international monetary system met with intransigence abroad, he proposed that Britain form an imperial currency bloc with a fixed-but-adjustable parity vis-à-vis gold. This would allow Britain to achieve the true purpose of monetary policy: domestic price stability.'