NEW YORK

His demobilisation, marriage and departure for New York at the end of the year, in 1915, marked another disruption in his life. From then on until the end of the war, the Gleizes' were travelling, living in hotels and temporary apartments. The impact made on him by New York was enormous and he is probably the first European avant garde painter (twenty five years before Mondrian's Broadway Boogie-Woogie) to try to capture its rhythms, the rhythms of the skyscrapers, advertising signs, traffic and jazz. And yet his enthusiasm was limited and doubts soon appear, mainly in his writings, notably The Miracle of Fifth Avenue (written in 1915, so at the beginning of his stay) in which he talks of a conflict between two 'spirits' – that which built the cathedrals and that which built the skyscrapers:

'Soon the insolence of the skyscraper would go beyond the dignity of their spires. The great altruistic word was lost under the raucous voice of the most small-minded egoisms.'

Yet in the Souvenirs he quotes an interview he gave at the time in which he says:

'The skyscrapers are works of art. They are creations of steel and of stone which are equal to the most admired creations of the Old World. The great bridges such as Brooklyn Bridge can stand comparison with the work of the men who built Notre Dame in Paris. The same strength has resolved the different problems that were posed by the needs of their construction.'

And his enthusiasm for 'les grands ponts comme Brooklyn Bridge' can be seen again in this extract from L'art dans l'évolution générale as well as in the Brooklyn Bridge paintings of the time:

'Without [the modern painters] initially planning it, their paintings intuitively reflected the new architectural laws. They are materially the brothers of the iron bridges and other modern constructions, they carry within themselves the same determining principles. Like them they are free from decorative embellishments, arabesques, pointless curves. Like them they advance towards another way of representing the world, they make use of the commands given by simple need and they satisfy them.

'As a result they are at the same time aggressive but without intending it. They break the convention by which the eye is bound to the always constant horizon line and, taking it by surprise, they force it into an effort against which it rebels.' [pp.123-4]

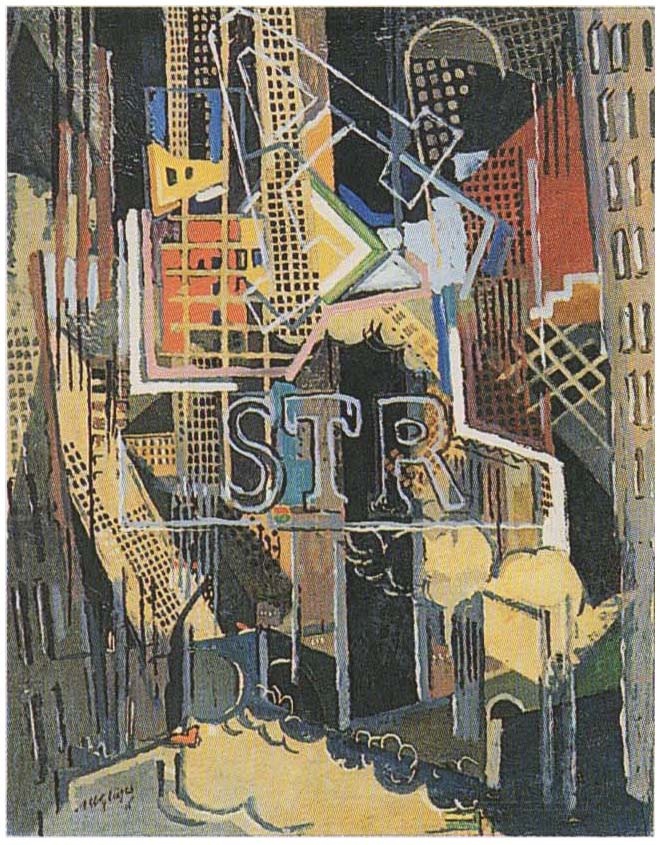

New York, 1916

Oil on canvas, 92 x 72.4 cm

Present whereabouts unknown

Here then is a moment in which Gleizes seems to be following the path traced out by the Italian Futurists and to be presenting himself as a poet of modern life. And this is what he seems to suggest in an important letter sent in 1917 to his old friend from the days of the Abbaye de Créteil, the poet Henri Martin Barzun:

'The awareness of the vast horizons that have been opened in front of me by trains and transatlantic ships have separated me forever from spaces that are metaphysical ... Our space [our normal three dimensional space, not the non-euclidean, 'metaphysical' or four dimensional space which was interesting Gleizes' colleague Metzinger – PB] hasn't been used as it should have been, far from being exhausted it opens up more multiple than ever ...

'We are in the age of synthesis. An hour in the life of a man today raises more levels, insights, actions, than a year of that of any other century. That is what I try to say in my art. The rapid sketch of an Impressionist crystallised the fragility of a sensation; it was immobilised in his picture. The painting of today must crystallise a thousand sensations in an aesthetic order. And I see that for that there is no need to reveal other laws, other theorems with definitive forms. A beauty achieved through a mathematical order can only have a relative life; the universal kaleidoscope cannot be fitted into the framework of a system; it surprises through the unforeseen and is renewed by it. We should regard 'the system' with suspicion. It limits our possibilities. How, for example, can we give the equivalent of the enormous 'Broadway' – that fantastic river with a thousand currents going against each other, interweaving, rising up over its banks – if, in our painter's expression, we apply little principles just about good enough to describe a very simple object, an inkstand, a box etc. With one blow, the truth blinds us [crève les yeux] and rises up to scatter the system's charm ...' (9)

(9) I originally thought that the letter, which I knew from an undated typescript, was written in 1916 but Pascal Rousseau ('L'Age des synthèses' in the Barcelona and Lyon retrospective cataloge Albert Gleizes, le cubisme en majesté, 2001, p.171) has found it in the Barzun archive giving the date as 24/8/1917.

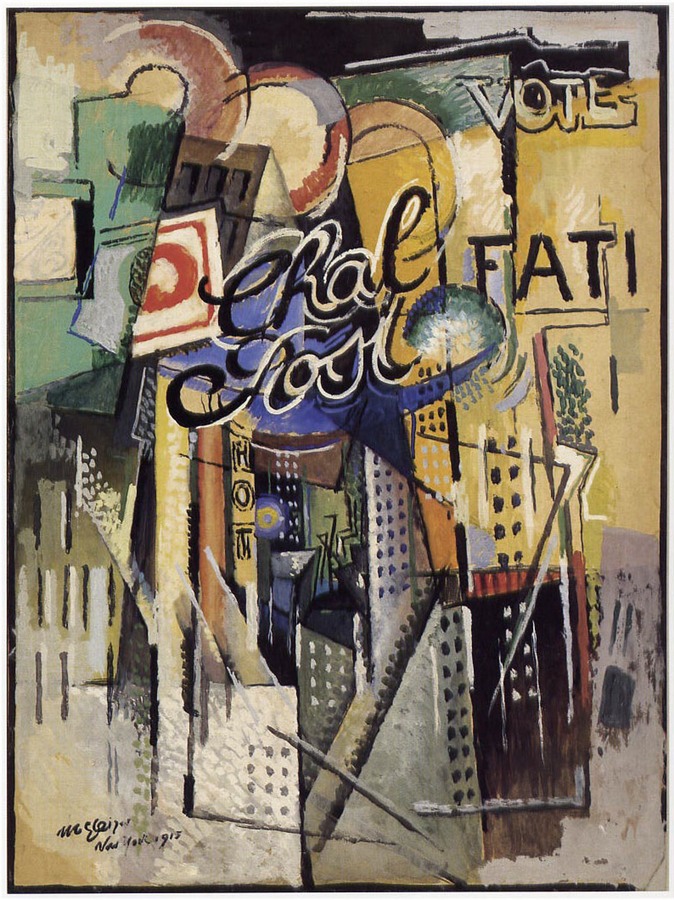

Broadway (Chal Post), 1915

Oil and gouache on card, 101.8 x 76.5 cm

New York, Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum

There is, then, a certain ambiguity in his attitude to the modern world. What seems to attract him on the one hand also seems to repel him. He is perhaps the first figure of the European avant garde to celebrate jazz, even before the composers took it up in the twenties, yet he tells us in the Souvenirs that when the musician Carlos Salzedo introduced him to it on his arrival in New York he did not at all like it

'We had never heard that. Paris hadn't yet been contaminated by this extraordinary music that seizes you in all it chaos, lulling you one moment in a sentimental fashion, then suddenly stopping to overwhelm you with a torrent of raucous, sharp, tender sounds and cries which draw you into a mad whirlpool which you cannot possibly escape ...'

He refers to dancers who are 'puppets obeying the demands of invisible strings.'

Composition pour Jazz, 1915

Oil on card, 73 x 73 cm

New York, Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum

He is also perhaps the first to celebrate the neon signs and advertising posters of Broadway but, talking of Broadway in the Souvenirs he says: 'In a period of a few hours we had approached the heart of America, a heart futile and hard, sentimental and dry.' Of course this reflects his later feelings after he had turned against all the manifestations of industrial civilisation, but the mixed feelings are still present in the writings of the time, for example, in the Cavalier du Dimanche:

'There are monsters in the town surrounding us, agitated and wasting themselves in sterile gestures. There is murder and boredom on the shining pavements. This evening the disaster is more supernatural than it usually is. All the poor people living in the miserable prts of the city must rise up in a crusade against the dignity of Fifth Avenue. A passive crusade, a long cortege which would take eight hours to pass. Perhaps then something would change and the nights would be opened up by the horror of it ...

'There are always the same images surrounding my new self, the same immobile images I now hate, the same images which nonetheless I indulged without any feeling of disgust, only a few centuries ago.'

or in L'Art dans l'évolution générale:

'Modern machinery is presented as a universal synthesis, but that is false. You might as well take an epidemic of cholera as a universal synthesis, war as a universal synthesis ...' [p. 138]

'The construction of a motor is less mysterious than the birth of the most humble plant, the structure of a body or of a tree is more surprising than that of a railway line.' [p.151]