GOVERNMENT POLICY AFTER THE POGROMS

Dubnow did not invent the thesis that elements of the Tsarist government or 'dark forces' close to government were behind the pogroms. It was widely believed at the time. In her essay The Origins of an enduring myth: the pogroms of 1881-2 in the British popular narrative (10) Sam Johnson, specialist in Jewish studies in the Manchester Metropolitan University, refers to 'two memoranda written in 1882. The first, the Gintsburg Memorandum presented to the Tsar on 22 March 1882 (OS) "established a template for attacks" on the Ministry of Internal Affairs, thereby implying that the forces of order had failed to quell the pogroms as a consequence of official directives. The Levin Memorial, written some time between May and June 1882 (OS) and which spoke of "dark forces" at work in the Empire, revealed in some detail the mechanisms by which the pogrom policy operated.' Johnson gives Klier's book on the pogroms as her source. Unfortunately when I was reading it in the British Library I didn't get that far in the time I had available. Johnson continues: 'According to Klier it was the latter memorandum especially that aided in the embrace of the pogrom myth in Russian and Western received opinion; not by coincidence, it was often referred to by Dubnow.' A review of Klier's book refers to 'a 250 page memorandum written by Emmanuel Levin that fully formulated arguments which produced the myth of the authorities' conspiracy in the pogroms.' It is described as 'the major product of the Gintsburg circle.' (11)

(10) Judaica Petropolitana No 4, 2015, pp.42-64. Judaica Petroplitana is an interesting phenomenon, a collaboration between the St Petersburg State University and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Its articles covering a very wide range of subjects of Jewish interest are available online - http://judaica-petropolitana.philosophy.spbu.ru/Main/intro_en.html

(11) Vladimir Levin: review of John Doyle Klier: Russians, Jews and the pogroms of 1881-1882, The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol 91, No.2 (April 2013), pp.369-372.

This has particular importance because the Gintsburg in question was the banker, one of the most powerful men and certainly the most powerful Jew in the Empire. Klier's book uses material that was difficult of access to Western researchers during the Soviet era and this may explain why the memorandum is not mentioned in an essay on the reaction of the St Petersburg Jewish leadership published in 1984 which nonetheless shows that the Gintsburg circle was very active at the time. (12) Principally they were anxious to fend off two, in their eyes, very dangerous ideas. The first, spreading rapidly among the Jews themselves, that life in the Russian Empire was impossible and that the only solution was emigration, whether to North America or to Palestine. The second was the idea being floated by the Minister, Count Nikolai Ignatiev, that the solution to the overcrowding of Jews in the Pale of Settlement would be to transfer them to underpopulated areas in S.E.Asia (we may be reminded of the Soviet project of Birobidzhan). Gintsburg and his circle wanted to keep the attention focussed on the question of equal rights, including the right to settle anywhere in the Empire. At the same time they were also anxious for a reform of Jewish life itself, encouraging both a more modern view of the world and the development of a wider range of productive craft and industrial skills.

(12) Alexander Orbach: The Russian-Jewish leadership and the pogroms of 1881-2: the response from St Petersburg, Carl Beck papers in Russian and East European Studies, Paper no 308, University of Pittsburgh, 1984. Orbach refutes very convincingly the common Jewish left wing view that the wealthy and powerful Jews of St Petersburg didn't try very hard to help their co-religionists, victims of the pogroms.

I mentioned earlier that the outbreak of the first pogrom in April 1881 had followed hard on the assassination in March of the 'Tsar-liberator', Alexander II by the 'Peoples Will' revolutionary group. The question of how that stands in relation to the pogroms raises the whole matter of the development of radical politics in the 1870s, relations between the radicals and the peasantry, the role played in the radical groups at that time by Jews (important in relation to the radical groups, almost insignificant in relation to the Jewish community as a whole), and the way in which the relationship between Jews and radicals was seen by the population at large. But I think all that requires a separate article. What is important here is the effect it had on government thinking and in particular on the government's response to the pogroms.

The minister of Internal Affairs at the moment of the first outbreak in Elizavetgrad was still Count Mikhail Loris-Melikov, scion of an important Armenian-Georgian family who had fought with distinction in the recent Russo-Turkish war (1877-8) and who had been appointed by Alexander II with the specific intention of developing a programme of constitutional reform. When it was clear that Alexander III had no intention of implementing these reforms he resigned and was replaced by Count Nikolai Ignatiev who, as Russian ambassador in Constantinople, had been largely responsible for fomenting the revolt in Bulgaria that led to the Russo-Turkish war. He had negotiated the Treaty of San Stefano whose terms were so unfavourable to the Ottomans that it prompted a European reaction and the restraint put on Russian ambitions by the Congress of Berlin.

The new mood was symbolised by the Manifesto of Unshakeable Autocracy issued on 29th April 1881 and reputedly written by Dostoyevsky's friend Konstantin Pobedonostsev, procurator of the Holy Synod. (13)

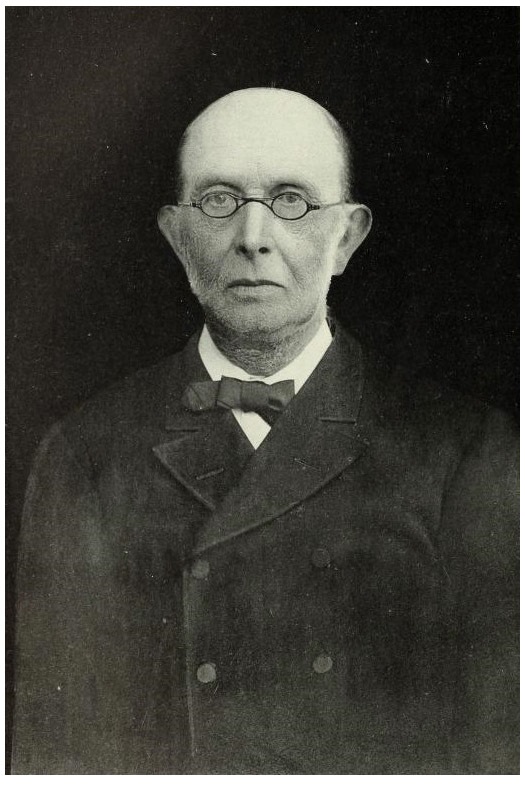

Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Photograph taken from The World's Work, New York, Doubleday, Vol VI, July 1903

(13) He assumed that role as it happens in 1880, still under the reign of Alexander II, who had also, of course, appointed him as tutor to his son, Alexander III. Dostoyevsky and Pobedonostsev had come to know each other as members of a literary circle formed round Prince V.P.Meshchersky 'who had founded a new publication, Grazhdanin (The Citizen), to counter the influence of the liberal and progressive press' (Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky, the mantle of the prophet, 1871-1881, Princeton University Press, 2002, p.18). The circle also included the poet Feodor Tyutchev. Frank points out that at this time Pobedonostsev 'was regarded primarily as a legal scholar and highly placed government official with a liberal past (in the Russian sense).' He became 'tutor' to Alexander in 1865 when Alexander was already 20 years old so the term 'tutor' is a little misleading. 'Counsellor' might be better. He continued to be close to him all his life and Frank quotes letters in which Pobedonostsev tells Dostoyevsky of the tsarevich's interest in his novels.