Back to article(s) index

Previous

Technology - the Radio and the Clone

Second editorial published in the Heidegger Review, No.1, July 2014.

DESTRUCTION OF THE VILLAGE

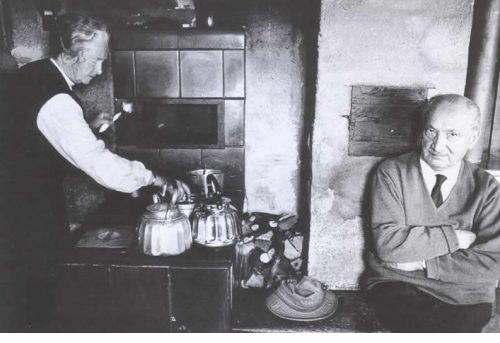

Heidegger resisting the blandishments of technology

Technology, by its nature, leaves what we say behind. It is difficult now to tune in to some of what Heidegger says about it. For example, denouncing the effects of Nazi policy on rural Germany:

“People preach about ‘Blood and Soil’, and they carry on urbanisation and destruction of the village and the family farm on a scale that a short time ago no one would have imagined... ‘The countryman’, who once walked the fields; and the nutrition industry worker, well provided with radio and cinema, who has to do with ‘tractors’ and his ‘motorbike’. The fight against ‘urbanisation’ is senseless when already the country is more ‘urban’ than the town” (XI, 1; XIV, 84).

What’s all that about? Why shouldn’t a farmworker have his radio and go to the pictures on his motorbike?

In 2014 that question can’t really be discussed. It’s a pre-television, pre-combined harvester, pre-baler, pre-milking machine sort of question. Definitely it’s pre-electricity, bringing with it the smell and flicker of oil lamps and lanterns and old-time ranges. It comes from a time when some people still thought that the world should have places in it that were not urbanised.

In the 1920s and 1930s any number of gifted writers racked their brains for solutions to problems that we now know were insoluble. For example, rural depopulation, death of the peasantry, flight from the land. This problem was as old as the industrial revolutions and it grew as industry grew. More recently there had been a response in modern politics, including in the young labour movement. (I remember hearing that even at the time of the Great Depression Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister of Britain, declared that a “Back to the Land” movement would have to be part of the solution.)

By the late 1930s, however, those who wanted to save rural Europe were pessimistic. The German situation was depressing. Though it was Nazi Party policy to save the German countryside, the flight from the land continued apace under the Nazis, and the government with all its powers was forced to admit that it had no idea how to stop the exodus. There’s more than a whiff of pessimism, I think, in Article 45, 2, v of the Irish Constitution of 1937: “The state shall... direct its policy towards securing... that there may be established on the land in economic security as many families as in the circumstances shall be practicable.”

Simone Weil, writing in 1940, had this to say: “It is obvious that a depopulation of the countryside leads, finally, to social death. We can say it will not reach that point. But still, we don’t know that it won’t. So far, there seems to be nothing which is likely to arrest it.” (The Need for Roots, 1987, p. 78.)

What did she mean by “social death”? - I think people like Weil and Heidegger believed that society needed to have roots where everything else that grew had its roots: in the land. There needed to be communities living on the land and spiritually framed by the land, and not bound up with the artificial life of towns.

Still, wherever you lived the town would come looking for you, offering its gifts. The motorcycle made regular trips to town easier. Motorised farm machines came between the farmworker and the land. The cinema showed him urban visions, and the radio tuned him in daily to urban thinking. All of this undermined the morale of the rural community as such.

“The inferiority complex in the countryside is such that you see peasant millionaires who find it natural to be treated by retired petit bourgeois with the sort of arrogance shown by colonials towards natives. An inferiority complex has to be very great for money not to be able to wipe it out,” Simone Weil said.

Weil and Heidegger knew that their ideas were being challenged. Missionaries were at work all over Europe, preaching that everything had to be urbanised. Foremost among them, of course, were the Bolsheviks. But though Bolshevism was the most vocal, it was not the most effective. As Heidegger pointed out elsewhere, it was in England that modernity first developed, and England was also a pioneer in producing attitudes of mind for accepting what modernity brought. English culture was better at bringing people to a satisfied feeling of progressing while holding the line, as compared with crude Bolshevism, which left raw nerves everywhere. This is what Heidegger means by saying that “the bourgeois-christian form of English ‘Bolshevism’ is the most dangerous” - a statement which Jürgen Kaube quotes mockingly, as if it were transparently absurd.

Francis Bacon, the great English philosopher, the genius who foresaw technological society centuries before it happened, was already very plausible and reassuring. He encourages us not to be afraid of a society based on experimental science. Always, whenever we need to, we will be able to hold the line. (For example, religion will not be abandoned.)

I’m not certain of this, but I think we cannot accuse Bacon of promising we could hold on to country life. His model society, the New Atlantis, seems to be urbanised through and through. The New Atlantis is a hyper-technologised island where “we have... we have... we have... we have...” I would say that modern capitalist society can be described as the ongoing quest for the New Atlantis, as yet not attained.

Anyhow, since World War II we have entered the age of urban totalitarianism. Europe is thoroughly urbanised across its length and breadth. There are fewer people in rural parts, but that doesn’t matter because there are more, bigger, better machines and a lot more food is produced. And where Europe has led, the world is following. Everywhere will be urbanised, though people continue to stream from an urbanised countryside into the urban spaces proper. We now have a world where most people live in the larger towns and cities.

Along with this breakneck urbanisation, world population has rocketed. It’s not long since the death of a man who devoted his life to showing the West what it was destroying: Claude Lévi- Strauss. In his last interview he remarked that in 1908, when he was born, there were one or one and a half billion people in the world. As he neared the age of 100, the figure was over six billion. Since then it’s gone over 7 billion. And these billions are involved in a world system which depends on the principle that, if everyone chases the New Atlantis, everything’s going to work out. (Statistics can be provided to show that the situation is good. The indicators are improving.)