PARVUS AND THE BREAK-UP OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

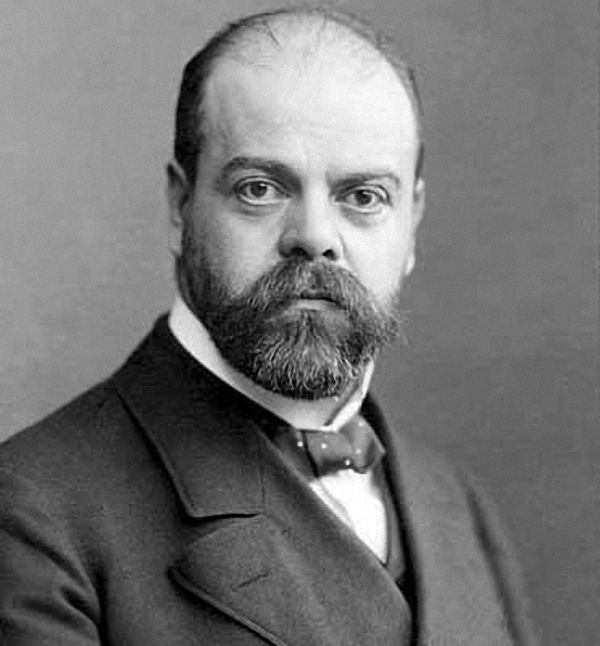

Alexander Hephand ('Parvus')

Following the February Revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government which took power in Petrograd was immediately faced with demands for independence from 'the Duchy of Finland' and from the 'Kingdom of Poland'. The Kingdom of Poland, with its capital in Warsaw, was made up of areas which had originally been taken in the eighteenth century by Prussia and Austria but were then taken in 1807 by Napoleon as part of his 'Duchy of Warsaw'. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815 the formerly Austrian part of the Duchy and most of the formerly Prussian part were ceded to Russia which was at the time the occupying power. The 'King' of the Kingdom of Poland was the Tsar. By the time of the revolution however the whole area was in German hands and the 'Central Powers' (Germany and Austria) had promised it independence, leaving the Russian Provisional Government little apparent choice in the matter.

Finland, which was still under Russian control and which was not at the time an area of military operations presented more of a problem. As the Tsar was King of the Kingdom of Poland so he was Duke of the Duchy of Finland. Finland, previously attached to Sweden, had been incorporated into the Empire in 1809 at a time when Russia was in alliance with Napoleon in opposition to Sweden. It had a notionally autonomous status within the Empire perhaps rather like the relationship of Scotland to England within the United Kingdom. A sense of Finnish national identity and use of the Finnish language had actually been encouraged under Alexander II in opposition to the largely Swedish ruling class and Finland had developed its own industrial base, working class and liberal and Socialist politics which came into violent confrontation with what were seen as the policies of Russification associated with Nicholas II and his governor-general Nikolai Bobrikov, assassinated in 1904 - policies continued after 1905 by Stolypin.

In opposition, of course, the liberal and Socialist parties now in power in the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet had been broadly supportive of the non-Russian nationalities within the Russian Empire, albeit with different ideas as to what the rights of minorities might be. But now they were in government and in a state of war with the Central Powers who were very aware of the opportunities presented by the multinational character of Russia. If they hadn't been able to figure that out for themselves they were reminded of it by no less a person than Alexander Helphand - 'Parvus' - the Social Democrat theorist of 'permanent revolution', adviser to the Young Turk government in Istanbul, successful businessman who Solzhenitsyn sees, controversially, as a major influence on, or at least tempter of, Lenin, presenting the logic of seeking German support for the Russian revolution. (1)

(1) Solzhenitsyn's fantasy of a confrontation between Parvus and Lenin in 1916 can be found in November 1917, Penguin Books, 2000, pp.635-678. I discuss it in my essay 'Solzhenitsyn's Jews - Parvus and Bogrov', Church and State, No.125, October-December, 2016, available on my website at http://www.peterbrooke.org/politics-and-theology/solzhenitsyn/parvus/ It should be said that in Solzhenitsyn's account Lenin resists Parvus's temptation. The standard account of Parvus's life is ZAB Zeman and WB Scharlan: The Merchant of Revolution - the life of Alexander Israel Helphand (Parvus), 1867-1924, Oxford University Press, 1964.

THE KONSTANTINOPLER AKTION

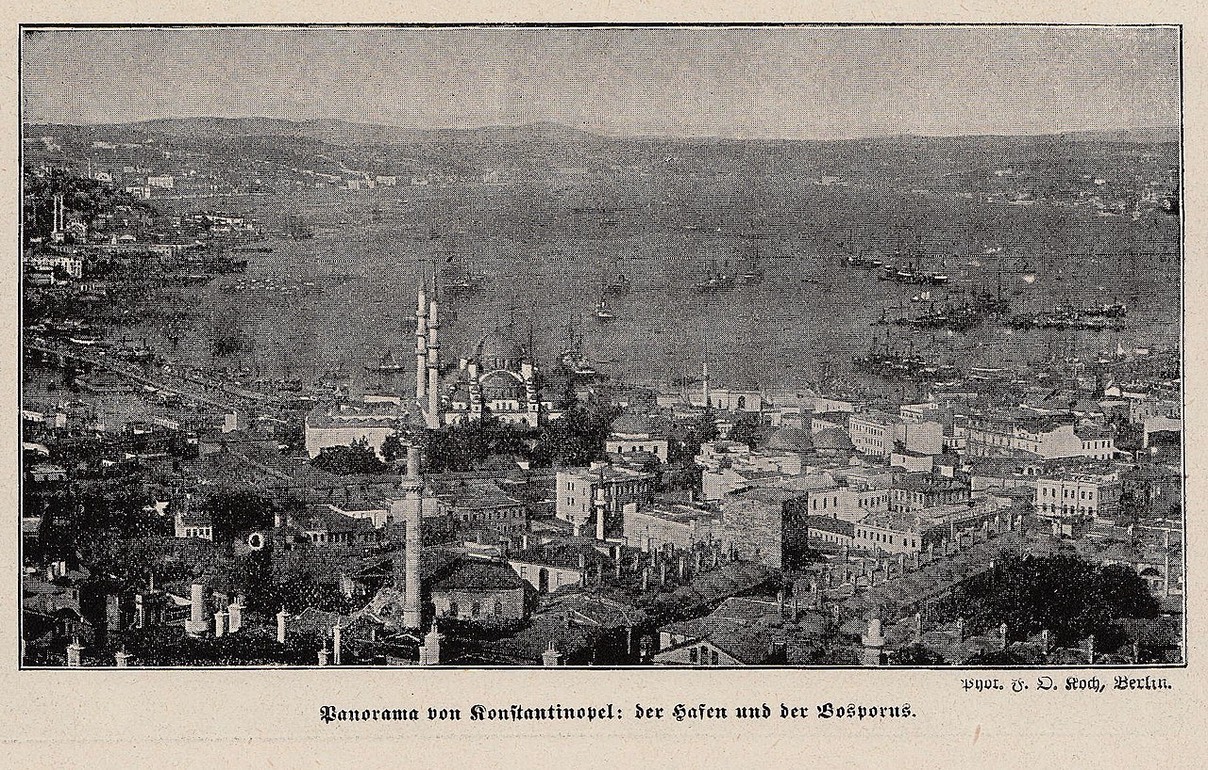

Constantinople in 1914

When the war broke out Parvus was in Istanbul, where he made contact with the 'Union for the Liberation of Ukraine' (SUU). (2) The Union had been founded in Austrian Galicia - Lemberg/Lwow/Lviv - at the beginning of the war and quickly established representation in Germany, Switzerland, Turkey and Bulgaria. The representative in Turkey was Mariian Melenevsky, aka 'Bako'. Melenevsky had been one of the founders in 1904 of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Spilka (union) which had, in opposition to the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party, joined up with the Menshevik wing of the RSDRP. According to Zeman (p.133), Parvus and Melenevsky had known each other back in the days of Parvus's involvement with the journal Iskra. (3) Melenevsky had the support of the German Dr Max Zimmer and in 1914 the German Ambassador in Istanbul, Hans Baron von Wangenheim, wrote to the German Foreign Ministry:

'The well-known Russian Socialist and publicist, Dr Helphand, one of the main leaders of the last Russian Revolution, who was exiled from Russia and has, on several occasions, been expelled from Germany, has for some time been active here as a writer, concerning himself chiefly with questions of Turkish economics. Since the beginning of the war, Parvus's attitude has been definitely pro-German. He is helping Dr Zimmer in his support of the Ukrainian movement and he also rendered useful services in the founding of Batsarias's newspaper in Bucharest. In a conversation with me, which he had requested through Zimmer, Parvus said that the Russian Democrats could only achieve their aim by the total destruction of Czarism and the division of Russia into smaller states. On the other hand, Germany would not be completely successful if it were not possible to kindle a major revolution in Russia. However, there would still be a danger to Germany from Russia, even after the war, if the Russian Empire were not divided into a number of separate parts.' (4)

(2) Account in Hakan Kirimli: 'The Activities of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War', Middle Eastern Studies, Oct 1998, Vol.34, No.4, pp.177-200.

(3) Iskra continued publication until 1905 after Lenin broke with it in the Bolshevik/Menshevik split of 1905).

(4) M. Asim Karaömerli̇oğlu: 'Helphand-Parvus and his impact on Turkish intellectual life,' Middle Eastern Studies, Nov. 2004, Vol. 40, No. 6, p.149.

Even before Turkey formally entered the war the SVU/ULU was involved in planning a Turkish assault across the Black Sea, either on Odessa or on the Kuban, in the Caucasus, modern Krasondar Krai, on the East Coast of the Black Sea where there was a substantial 'Ukrainian' population, the 'Kuban Cossacks', descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks after they had been broken up at the end of the eighteenth century. Unlike in Ukraine as centred on the Dnieper river, but like the Don Cossacks, the Kuban Cossacks had been allowed to maintain a distinct Cossack tradition, incorporated as a regiment in the Russian army - rather like the highland regiments incorporated into the British army after the suppression of the distinct Scottish political identity of the Scottish highlands. The Turkish project in the event came to nothing (the idea that the Kuban Cossacks would have taken kindly to a Turkish invasion was especially absurd) but this account of it by the Turkish historian Hakan Kirimli still makes interesting reading:

'By November 1914 (when Turkey entered the war) the plan of landing a Turkish expeditionary force involving the ULU crystallized and came to be known among the circles of the Central Powers as the 'Constantinople Action' [Konstantinopler Aktion]. The final details of the 'Constantinople Action' were presented to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Office during the first week of November by Basok-Melenevs'kyi, who then travelled to Vienna. In his private letter to Colonel Hranilovic of 8 November 1914, Count Hoyos [chef de cabinet to the Austrian Foreign Minister Count Berchtold - PB] summarized the plan and his opinion of it. As explained in this letter, the emissaries of the ULU had discussed with Enver Pasha's representatives in Istanbul Turkish-Ukrainian military co-operation in order to instigate a revolutionary movement in Ukraine by landing on the Russian Black Sea coast a small Ukrainian detachment protected by strong Turkish forces.

'In conformity with the discussions in Istanbul, the ULU requested from the Austro-Hungarian government an expeditionary corps of 500 Ukrainians, composed of 400 Austro-Hungarian Ukrainian legionaries and 100 Ukrainians to be selected from among the Russian prisoners of war. Hoyos asked Hranilovic to seek the approval of the Army Supreme Command to implement this plan. Then Colonel Fischer in Bukovina would be entrusted with choosing from among the personnel of the Ukrainian Riflemen [Sichovi Stril'tsi] the 400 legionaries who would necessarily be all volunteers. As for the 100 volunteers from among the prisoners of war, Colonel von Steinitz would authorize their selection. With this in mind, Hoyos suggested establishing a separate prisoner of war camp for the purpose of conducting revolutionary propaganda where suitable elements for the expedition would be selected. An officer of the Ukrainian Riflemen, as well as a representative of the ULU would also go to Bukovina to help select volunteers

[…]

'While Basok-Melenevs'kyi and Zimmer were in Vienna, they discussed the plan with Hoyos in detail. According to this, the landing was to be in the Kuban region with a Turkish expeditionary force of 50,000, supplemented by the above-mentioned 500 Ukrainian volunteers. The primary aim would be to provoke an uprising among the Kabardians and Kuban Cossacks. Zimmer himself would also take part in the venture, and it was hoped that the presence of the Ukrainian legionaries would be of particular operational use in stirring unrest among their ethnic kinsmen, the Kuban Cossacks. If the operation were a success, a nucleus of the Ukrainian state could be established there, and the Ukrainian movement could be expected to spread toward the west.

'However, all these plans were yet to be cleared by Turkey. Upon their arrival in Istanbul, Basok-Melenevs'kyi and Zimmer would seek the approval of Liman von Sanders and Enver Pasha. To obtain this, Hoyos asked Pallavicini [Johann Markgraf von Pallavicini, Austro-Hungarian diplomat, notably serving as ambassador at the Sublime Porte during World War I - PB] to contact Enver Pasha and von Sanders. In fact, as Hoyos stated, the Austro-Hungarians preferred a landing in Odessa over an expedition in North Caucasus. The latter option would be acceptable only in the case of a complete abandonment of the Odessa action, or if both operations could be carried out simultaneously. These were, however, not Hoyos' only reservations about the 'Constantinople Action.' He strongly favoured entrusting command of the Turko-Ukrainian expedition to the Austrian General Staff officer Count Szeptycki. For not only would the presence of an Austrian commander have a bearing on further developments in Ukraine (or rather the Kuban region), but it would also demonstrate that his country was not totally reliant on the Germans.

[…]

'Notwithstanding the euphoria of Basok-Melenevs'kyi, Zimmer, Nebel and the qualified enthusiasm of Hoyos, it soon became apparent that their optimism was premature: Turkey, which was supposed to bear the brunt of the operation, seemed to demur, to say the least. Pallavicini's telegram to Hoyos on 16 November 1914 made it clear that, although Enver Pasha agreed in principle with the idea of landing an expeditionary corps in the Northern Caucasus, this could only occur if control of the Black Sea could be fully secured, and that temporary control would not do. If the 500 Ukrainian legionaries cared to undertake the operation alone, Enver Pasha would be ready to take them to the Black Sea and have them landed in a designated spot; but once landed they would be on their own [auf eigene Faust operieren]. General Liman von Sanders was of a similar opinion, that landing a large force before securing total control of the Black Sea would be impractical. Even Pallavicini thought that Turkey should not commit itself to the operation until the position of the Bulgarians became absolutely certain.'

It's rather noticeable that in all this there is no hint of any contact with Ukrainian political groupings inside the Russian Empire, just an assumption that they would respond favourably to a Turkish invasion accompanied by a handful of Galician Ukrainians.

In March 1915 Parvus submitted to the German Foreign Ministry what Zeman (p.145) describes as 'a plan, on a vast scale, for the subversion of the Tsarist Empire' through using the revolutionaries (especially the Bolsheviks), nationalists (especially Ukrainians and Finns) and international public opinion (for example Jews and Slavs in exile in the United States). Of Ukraine he argued, in Zeman's account: 'The Ukraine was the cornerstone which, once removed, would destroy the centralised state.' Zbigniew Brzezinski wasn't the first to think of it. Parvus was less sure about the Caucasus given the contradictions between the attractive possibility of a Muslim Holy War, and the need to secure the co-operation of the Christian Armenians, Georgians and Kuban Cossacks.

As a result of his memorandum Parvus received a grant from the German government of one million marks. It is unclear what he did with it. The literature on the subject turns mostly on how much, if any, went to the Bolsheviks. The Union for the Liberation of Ukraine was represented (three members out of thirty four) on the 'General Ukrainian Council' formed in May 1915 in Vienna. The Council, overwhelmingly made up of Galicians with seven representatives from Bukovyna, advocated an independent Ukraine in the territories under Russian rule but only autonomy for Ukrainians in the territory that had been under Austrian rule and had now become a battle zone. Its position was totally undermined, however, when, as part of the recognition of an independent Poland in November 1916, restoration of an autonomous Polish dominated Galicia within Austro-Hungary was agreed.

It may be that the most important achievement of the SVU/ULU was its propaganda work among Ukrainian prisoners of war, mentioned in the last article in this series. In August 1917, according to the French historian Marc Ferro: 'The [Russian] press noted that among "wounded" prisoners sent back from Germany, 50% were unharmed and these were, precisely, Ukrainians.' (5)

(5) Marc Ferro: 'La Politique des nationalités du gouvernement provisoire (Février - Octobre 1917)', Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Vol.2, No.2 (April-June 1961), p.160, fn 124. My translation.