BENEDICTINES AND THOMISTS

There is a letter from Gleizes, dated 1929 and addressed to a Benedictine monk, in which he declares that the way of the future for the Church lies with the Benedictine tradition with its emphasis on prayer and manual work. He describes his own conversion as based on his experience as a painter:

'A Catholic by birth [...] Like many boys of my generation I had only given a very distracted attention to the things of religion; moreover I had judged them, following the spirit of the times, as incompatible with modern knowledge; I was a believer in progress'. But his own craft had obliged him to turn to 'theology which alone clarifies the difference between the absolute and the relative - that deeply affecting simplicity which allows no confusion between cause and effect [...] the moment when God taught me that without Him, all philosophical speculations and scientific calculations are in vain ...'

The aspiration towards the Absolute was built into human nature and explains both the aspiration of the scientist to a universal knowledge and his own ambition to incorporate ever larger subjects into his painting as well as the Unanimism of Jules Romains and René Ghil's attempt at a poetic synthesis of the history of the Universe (a word that means, as Gleizes liked to remind us, 'the one that turns'). We might also be reminded of Picasso's horror of 'the whole of it'. But the Absolute could not be achieved by the ever greater accumulation of data concerning the outside world, by attempting to expand the relative to the largest possible size. The problem of the relation between Absolute and Relative was a religious problem. Relative and Absolute were inseparable, yet no amount of relatives could add up to an Absolute. Yet it is only in relation to the Absolute that the relative acquires its full human value.

In both the philosophical and scientific worlds there were signs of an awareness of the problem:

'In the circles of the intellectuals religion is again becoming necessary to them, they are turning towards it. But by what door do they think of entering in? By the easiest, that which demands the least by way of renunciation, the least humility, that in which, on the very threshold, all the intellectual values of the urban university are to be found, where Aristotle's philosophy rules supreme, where they are taught, as a priest told me one day, seeming to think it the most natural thing in the world, that in Heaven St Augustine barely touches St Thomas's ankle. In a word, the Dominican door ...

'The real door ... that will open on the order of St Benedict, exclusively theological and for that very reason guardian of a way of doing things that is living, in accordance with the scale of magnitudes of the individual – work with the hands as the necessary complement to intellectual work, authority given to the agricultural countryside and restoration of monastic schools in which culture and technique are defined so well in the two categories of the trivium and quadrivium.' (28)

(28) The letter was almost certainly addressed to the Abbot of the Santa Maria de Montserrat monastery in Catalonia, which Gleizes had visited in 1929. I have it from the now dispersed Viaud archive.

Gleizes's refusal of the thirteenth century in general and of Thomas in particular put him out of sympathy with the mainstream of twentieth century Catholic religious art, even when (as in the case of Eric Gill, greatly admired as he was by Coomaraswamy) it shared his rejection of the Renaissance and his emphasis on the manual crafts. Those who rejected 'the Renaissance' tended to turn (like the 'Pre-Raphaelites' before them) to the early Renaissance, the 'Italian primitives' of the thirteenth century. Two notable examples were the old 'Nabi' painter Maurice Denis and Gleizes's friend from the days of pre-war cubism, the Italian Futurist Gino Severini. After making a distinguished contribution to the wartime Cubist group gathered round Léonce Rosenberg, Severini had called for a return to what he called 'Classicism', a geometrically based art which respected fully the laws of single point perspective but aimed to renew with the purity and simplicity of the thirteenth century. (29) Severini secured the enthusiastic support of the leading Thomist theorist, greatly admired by Gill, Jacques Maritain and was given many commissions for church decoration in the 1920s and 30s, especially in Switzerland and Italy. Denis in the 1920s had established the Ateliers d'Art Sacré, also arguing for a 'modern' approach to church decoration. Inbuilt into the proposal was a philosophical formation on the basis of Thomism.

(29) Gino Severini: Du Cubisme au Classicisme – esthétique du compas et du nombre, Jacques Povolozky, Paris 1921. English translation, From Cubism to Classicism, Francis Boutle publishers, London, 2000, published together with Gleizes's Painting and its laws. In the introduction I argue that Gleizes's book, the first clear statement of his cyclical view of history, was written partly in response to Severini.

Gino Severini, Third Station of the Cross, St. Peter's Church, Freiburg, 1928

In the immediate aftermath of the War the Dominicans Frs Pie Raymond Régamey and Marie-Alain Couturier (associated in the interwar years with Denis's Ateliers d'Art Sacré) launched a programme of employing well-known artists - famously Léger, Le Corbusier and Matisse - in the work of church building and decoration. It looked for a brief moment as if Gleizes could benefit from this development but relations soon soured. Régamey in particular was deeply hostile to Gleizes. He was championing the ideals of freedom and variety of expression among artists and he accused Gleizes, with his insistence on the 'laws' of the organisation of the picture plane and the interaction of colours, of 'desiccated academism', of wanting to impose a new straitjacket on the freedom of the artist: 'the craft you talk about isn't "the craft", with a universal value – but your own conception of the craft, that there is also Braque's craft, Picasso's craft, Manessier's craft etc etc ...' (30)

(30) From a letter by Gleizes's friend Jean Chevalier to Gleizes, 27/1/1948, describing a 'bagarre' he had with Régamey at a major retrospective of Gleizes's work shown in Lyon in 1947.

Régamey was especially annoyed with Gleizes's insistence that a truly human art had to take account of the human property of time, of mobility:

'Gleizes does not want the contemplative, placing himself at the necessary distance, to embrace the whole of the painting with a single glance. That is a passive and profane attitude. As for us, we find every day that it can be eminently contemplative. But no! this eye must wander and turn about the surface, following the directions of the cadence to finish up at rest in the "rhythm" of Eternity.' (31)

(31) Régamey: ‘A la recherche de la tradition’, Art Sacré, May-June 1948.

Gleizes did, however, receive support in the post-war period from the Benedictine Abbey of Ste Marie de la Pierre-qui-Vire and especially the young monk - a novice when he first made contact with Gleizes - Angelico Surchamp and his brother Dom Claude Nesmy. Gleizes can thus be regarded as godfather to Dom Angelico's extraordinary publishing venture, the Zodiaque series of books on Romanesque art. Soon afterwards, towards the end of his life (he died in 1953) he entered into contact with the group of Jesuits based in Fourvière, in Lyon, who were responsible for the Sources Chrétiennes series of scholarly texts and French translations of the early Greek and Latin Fathers of the Church. Through them he secured his only commission from the Church - at least the only one actually realised - for a fresco in the church of the new Jesuit seminary of Les Fontaines, Chantilly. By way of contrast to Régamey, Fr Viktor Fontoynont, 'the first “godfather” of the Fourvière group and the original architect of the Sources Chrétiennes project' was reported as saying, when he saw the maquette for Gleizes's fresco:

'See how the true tradition of Christian iconography is appearing once again in its simplicity. The human figure is transcended [dépassée] without being eliminated [évincée]; symbolism and history are brought together easily in harmony and rhythm.' (32)

(32) Quotation on Fontoynont from Paolo Prosperi: 'The Birth of Sources Chrétiennes and the return to the Fathers', Communio 39, Winter 2012, pp.641-62. Quotation from Fontoynont from Henri de Montrond: 'Une Fresque de Gleizes réalisée en équipe à Chantilly "Les Fontaines" - Le Cadre', Atelier de la Rose, no 9, March 1953, reproduced in L'Atelier de la Rose, Busloup, éditions du Moulin de l'étoile, 2008, p.177.

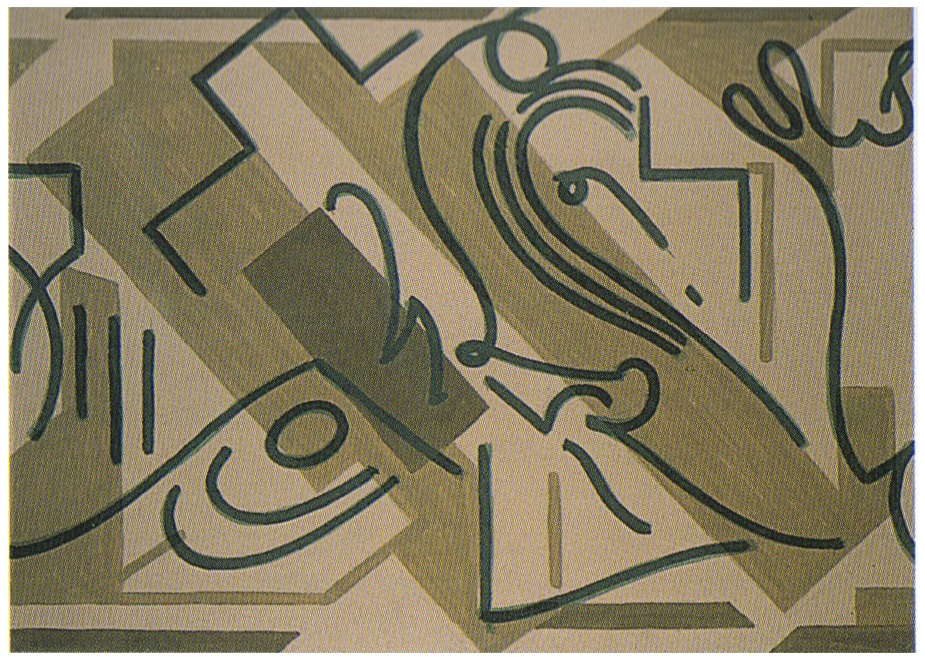

Gleizes: Project (unrealised) for a Stations of the Cross, 1951. A photo of the fresco in Chantilly can be seen in the article 'Cubism and Tradition', also on this website

As for Dom Angelico, shortly before his death he wrote:

'Gleizes said: "The modern movement brings us back not to traditions but to Tradition." Well, if we study primitive arts we see that they evoke the same principles. We find spirals and concentric circles at Gavrinis and New Grange, on the megaliths, on Chinese pottery or in Africa, as well as on the tympanums of Vézélay or Autun. That is the tradition which uses these signs that are inscribed in our humanity at its deepest level, but which have been more and more hidden from us through the imitation of nature. To the static nature of classical art the dynamism of the primitive arts stands opposed. Mobility and rhythm are essential in the earliest art because they show us life, and God is the Living, the source of Life.

'I owe everything to Gleizes and his influence on me remains profound. Firstly on the technical level. The works of the studio while it existed [L'Atelier du Coeur-Meurtry, established in the Abbey while he was working with Gleizes, in 1948 - PB] was proof that this technique does nothing to inhibit our own distinct personalities. And then, fundamentally, he brought me back to the Fathers of the Church, above all to Saint Augustine, and Romanesque iconography changed me utterly. Nevertheless it was from Gleizes that I received the keys to understanding it.' (33)

(33) Dom Angelico Surchamp; 'Je lui dois tout!', in Dom Angelico Surchamp, moine et artiste, Issy-les-Moulineaux, Beaux Arts/TTM editions, 2012, p.40.

It would of course be impossible to argue that anything like the change in state of mind Gleizes saw as the way of the future has been accomplished. But the present state of the visual arts is not so healthy as to prove definitively that he was wrong. Rookmaaker's book, fifty years old as it is, describes a malaise that is still with us. Unlike virtually any other period we can think of, the twentieth century, still less the twenty-first, seems to lack a coherent style, a coherent sense of purpose. There did seem to be a sense of a collective future, a collective adventure in painting prior to the First World War. Traces of it continued in the inter-war period but since the Second World War it just seems to have been one thing, one fashion, after another. We could celebrate this as an unprecedented age of freedom and variety but equally we could complain that it is going nowhere. It would, however, be difficult to point to any twentieth century artist with a more coherent sense of a possible direction for painting in relation to the whole of our intellectual life, than Albert Gleizes. His analysis of the problem we face is not a million miles removed from that of Rookmaaker. Unlike Rookmaaker, though, he proposed a solution.