THE EVIDENCE

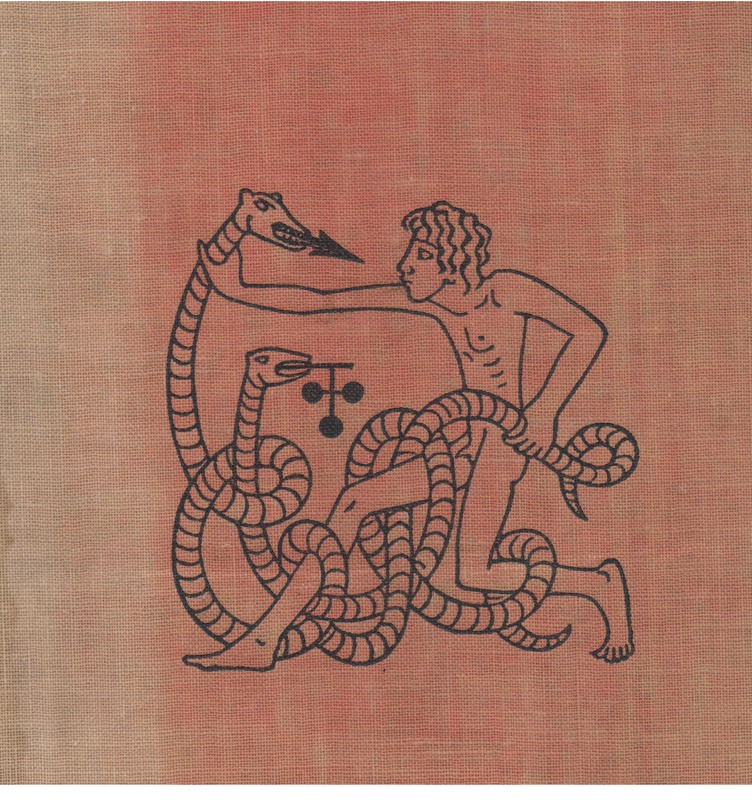

From the cover of Eric Gill: Art and a changing civilisation, 1934

But this brings us to the question of sexual relations with his daughters. Considering the impact her revelations have had on Gill's reputation, MacCarthy's attitude, expressed in the Introduction (p.viii), is surprisingly casual:

'There is nothing so very unusual in Gill’s succession of adulteries, some casual, some long-lasting, several pursued within the protective walls of his own household. Nor is there anything so absolutely shocking about his long record of incestuous relationships with sisters and with daughters: we are becoming conscious that incest was (and is) a great deal more common than was generally imagined. Even his preoccupations and his practical experiments [sic. She only mentions one - PB] with bestiality, though they may strike one as bizarre, are not in themselves especially horrifying or amazing. Stranger things have been recorded.'

Well, yes, certainly, stranger things have been recorded. But, she continues: 'It is the context which makes them so alarming, which gives one such a frisson. This degree of sexual anarchy within the ostentatiously well-regulated household astonishes.'

But what is truly astonishing is the change of mood that occurs at the end of her introduction: 'No one who knew him well failed to like him, to respond to him. And his personality is still enormously arresting. In his agility, his social and sexual mobility, his professional expertise and purposefulness, the totally unpompous seriousness with which he looks anew at what he sees as the real issues, he seems extremely modern, almost of our own age.' (p.xiii) But maybe she is wrong about 'our own age' catching up with Gill's 'sexual mobility.' At least if the man chipping away at the BBC's Prospero and Ariel can be taken as representative of our age. Indeed in an article written for The Guardian she suggests that 'Gill in 2006 would no doubt be in prison.' (16)

(16) Fiona MacCarthy: 'Written in stone', The Guardian, 22nd July 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/jul/22/art.art

The only deeds she records that could have landed him in prison are of course his sexual relations with his two eldest daughters, Elizabeth and Petra. This takes up one paragraph in MacCarthy's book (pp.155-6):

"For instance in July 1921, when Betty was sixteen, Gill records how one afternoon while Mary and Joan were in Chichester he made her ‘come’, and she him, to watch the effect on the anus: ‘(1) Why should it’, he queries, ‘contract during the orgasm, and (2) why should a woman’s do the same as a man’s?’ This is characteristic of Gill’s quasi-scientific curiosity: his urge to know and prove. It is very much a part of the Gill family inheritance. (His doctor brother Cecil, in his memoirs, incidentally shows a comparable fascination with the anus.) It can be related to Gill’s persona of domestic potentate, the notion of owning all the females in his household. It can even perhaps be seen as an imaginative overriding of taboos: the three Gill daughters all grew up, so far as one can see, to be contented and well-adjusted married women. Happy family photographs, thronging with small children, bear out their later record of fertility. But the fact remains, and it is a contradiction which Gill, with his discipline of logic, his antipathy for nonsense, must in his heart of hearts have been aware of, that his private behaviour was at war with his public image – confused it, undermined it. Things did not go together. There is a clear anxiety in his diary description of visiting one of the younger daughter’s bedrooms: "stayed ½ hour – put p. in her a/hole". He ends almost on a note of panic, "This must stop.’"

The paragraph begins 'For instance ...' and in the Guardian article I quoted earlier MacCarthy says that 'during those years at Ditchling, Gill was habitually abusing his two elder daughters' so we must assume that these are not the only examples. But so far as I know this paragraph is all there is in the public domain, the sole basis on which Gill has been characterised as a 'paedophile' (MacCarthy gives no examples of sexual relations with any others among the many young teenagers and children in Gill's circle). We're not told if these two incidents are typical, if similar things occurred frequently, if these are particularly bad cases, or if there is worse. Nor are we told, in the second case, if, when he says 'This must stop,' it did stop, or if this is - or isn't - the only case of penetration occurring.

YOU THE JURY

In 2017 the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft which has a very important collection of his work, put on an exhibition, Eric Gill - The Body, designed to face up to this embarrassing part of its legacy. This might have been an opportunity to explore the diaries further but it does not appear to have been taken. Instead the assumption was that all that needed to be known was known. To quote an account prepared by Index on Censorship: 'awareness of this aspect of his biography is widespread and has been fully discussed and debated.' (17) The approach was to invite visitors to the exhibition to respond to the works - many of them naked bodies, lovers embracing, detailed studies of male genitalia - in light of the knowledge that they were done by a man who abused his daughters. According to a statement by the Museum director, Nathaniel Hepburn:

'This exhibition is the result of two years of intense discussions both within the museum and beyond, including contributing to an article in The Art Newspaper in July 2015, hosting #museumhour twitter discussions on 22 February 2016 on ‘tackling tricky subjects’, a workshop day with colleagues from museums across the country hosted at the museum with Index on Censorship, and a panel discussion at 2016 Museums Association Conference in Glasgow. Through these discussions Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft feels compelled to confront an issue which is unpleasant, difficult and extremely sensitive. It has by no means been an easy process yet we feel confident that not turning a blind eye to this story is the right thing to do. This exhibition is just the beginning of the museum’s process of taking a more open and honest position with the visitor and we already have legacy plans in place including ensuring there will continue to be public acknowledgement of the abuse within the museum’s display.' (18)

(17) Julia Farrington: 'Case Study - Eric Gill/The Body', 15th May, 2019, https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/05/eric-gill-the-body-case-study/

(18) Nathaniel Hepburn: 'Eric Gill / The Body: Statement from the Director', https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/05/eric-gill-the-body-statement-from-the-director/

It was a delicate exercise. There were consultations with charities helping survivors of abuse, there were two writers in residence, helplines and support literature for people who could have been adversely affected by the content of the show. The sculptor Cathie Pilkington was co-curator and had a little exhibition of her own, based round a wooden doll Gill had made for Petra when she was four years old. In its atmosphere of high seriousness it was all a far cry from MacCarthy's summing up of the life at Ditchling, where the events described occurred (she says they didn't occur later):

'It was not an unhappy childhood, far from it. All accounts, from the Gill and Pepler children, the children of the Cribbs and the other Ditchling families, so closely interrelated through the life of the workshops and the life around the chapel, verge on the idyllic. Simple pleasures, intense friendships, great events – like the annual Ditchling Flower Show and the sports on Ditchling Common, with Father Vincent, as timekeeper, stopwatch in hand; followed by a giant Ditchling children’s tea party. There were profound advantages in growing up at Ditchling. But the children always felt – this was the price of self-containment – that it was other people who were odd.' (p.154)

Among the 'frequently asked questions' prepared for the exhibition, there was this:

'Isn’t it true that Gill’s daughters did not regard themselves as ‘abused’? They are reported as having normal happy and fulfilled lives and Petra at almost 90 commented that she wasn’t embarrassed by revelations about her family life and that they just ‘took it for granted’. Aren’t we all perhaps making more of this than the people affected?' (19)

(19) 'Eric Gill / The Body: Q&A for visitor services', htps://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/05/eric-gill-the-body-qa-for-visitor-services/

The quote comes from an obituary of the weaver, Petra Tegetmeier, which appeared in the Guardian:

'A remarkable aspect of those liaisons with Petra is that she seems not only to have been undamaged by the experience, but to have become the most calm, reflective and straightforward wife and mother. When I asked her about it shortly before her 90th birthday, she assured me that she was not at all embarrassed - 'We just took it for granted'. She agreed that had she gone to school she might have learned how unconventional her father's behaviour was. He had, she explained, 'endless curiosity about sex'. His bed companions were not only family but domestic helpers and even (to my astonishment when I heard about it) the teacher who ran the school at Pigotts' (20)

(20) Patrick Nuttgens: 'Unorthodox liaisons' (obituary for Petra Tegmeteier, 6th January, 1999, https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/jan/06/guardianobituaries. The title of the obituary shows how far the reputation of Petra Tegmeteier, a distinguished weaver, has been drowned in the afterflow of Fiona MacCarthy's 'revelations'.

The Museum's reply to the question was as follows:

'Elizabeth was no longer alive when Fiona McCarthy’s book was published, and those who met Petra certainly record a calm woman who managed to come to terms with her past abuse, and still greatly admired her father as an artist. I don’t think that we should try to imagine her process to reaching this acceptance as we know too little about her own experiences.'

'We know too little about her own experiences' but we do know that 'her past abuse' was a problem she had to come to terms with, despite her own statement that it wasn't. A certain disquiet about the position of Petra in all this is expressed by some of the people involved in the project. One of the writers in residence, Bethan Roberts, wrote a short story about her called 'Gospels' which was posted on the Ditchling Museum website but now seems to have disappeared. The other, Alison Macleod, commented: 'Yes, the biography is upsetting disturbing in part and there was clearly a history of abuse that is without question. But it is made slightly more complex by the fact that the two daughters [who] were abused said they were unembarrassed about it, not angry about it, loved their father, and didn’t give the response that perhaps I’m imagining, or some people expected them to give – to be angry about it and condemn their father’s behaviour. They didn’t. So maybe they have internalised their trauma, but you could say that that response is almost patronising to the two women, the elderly women who were very clear about what they felt, so it goes into a loop of paradoxes of riddles that you cannot really ever solve.' (21)

(21) Julia Farrington: Case Study.

The resident artist, Cathie Pilkington, carved a series of heads based on the doll Gill had made for Petra and labelled them 'Petra'. Steph Fuller, an artistic director of the Museum who said that she had been on the outside of the project but 'recruited while the show was on' felt uneasy about this:

'The real legacy issue, which I am grappling with at the moment, is that the voice that was not in the room, was Petra’s. She was very front and centre as far as Cathie’s commission was concerned, but there is something about how the work conflated Petra with the doll and being a child victim, that I’m a bit uncomfortable about actually. There is lots of evidence of Petra’s views about her experiences, and how she internalised them, that was not present at all anywhere. It is easy to project things on to someone being just a victim and Petra would have completely rejected that.

'In terms of legacy how we continue to talk about Gill and his child sexual abuse and other sexual activities which were fairly well outside the mainstream, I think – yes acknowledge it, but also – how? I am feeling my way round it at the moment. There are plenty of living people, her children and grandchildren who are protective of her, quite reasonably. I need to feel satisfied that when we speak about Petra, we represent her side of it and we don’t just tell it from the point of view of the abuser, to put it bluntly. If it is about Petra, how do we do it in a way that respects her views and her family’s views?' (22)

(22) Ibid

According to Rachel Cooke, who was brought in as a sort of resident journalist, Pilkington had commented on the doll: 'This is a very potent object. It looks to me just like a penis'. She continues:

'Her installation, central to which are five scaled-up versions of the head of Petra’s doll (one decorated by her 11-year-old daughter, Chloe), will explore different aspects of Gill’s practice, and the way we are inclined to project his life on to his work, sometimes in contradiction of the facts: “The tendency – if there is a picture of a figure – is to chuck all this interpretation on it… it can’t just be a beautiful drawing or a taut piece of carving. But sometimes it is. Where, I’m asking, is Petra in all this? There are aspects to her life apart from the fact that her father had sex with her.”' (23)

(23) Rachel Cooke: 'Eric Gill: can we separate the artist from the abuser?'

Exactly. Though I for one was left wondering how exactly her installation - a sort of doll's house full of little knicknacks including the doll's heads - contributed to our understanding that Petra and Elizabeth were something other than just victims of sex abuse, and that there was more, much more, to their relation with their father than the sex.

A catalogue was produced. (24) Apart from Cathie Pilkington's installation it consisted largely of highly representational life drawings including some of his studies of his friends' (male) genitalia. Material that will appeal to the 'art connoisseur' for whom Gill expressed such lofty contempt. It leaves me wishing that he had taken Thomas Aquinas's instruction to imitate nature in its way of working not in its effects - the renunciation of post-Renaissance representational art - more seriously. As Gleizes did, advancing into non-representational art, an art that Gleizes claimed (25) might eventually be worthy of comparison with the non-representational art of the oriental carpet.

24 Nathaniel Hepburn and Catherine Pilkington, curators: Eric Gill: the body, with Catherine Pilkington: Doll for Petra Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft, Exhibition catalogue, 230 April - 3 September, 2017.

(25) Unpublished ms note in the Gleizes archive formerly kept at Aubard.

MacCARTHY'S 'DISMAY'

Rachel Cooke quotes Fiona MacCarthy saying:

'she has watched in “dismay” as the fact of Gill’s abuse of his daughters has grown to become the thing that defines him. “My book was never a book about incest, which is what one would imagine from many hysterical contemporary responses,” she says. “It was a book about the multifaceted life of a multi-talented artist and an absorbingly interesting man.” As people demand the demolition of his sculpture in public places – the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral, Prospero and Ariel at Broadcasting House – she asks where this will end: “Get rid of Gill, but who chooses the artist with morals so impeccable that they could take his place? ... I would not deny that Gill’s sex drive was unusually strong and in some cases aberrant,” she says, “but to reduce the motivation of a richly complicated human being to such simplification is ludicrous.” Reducing art to a matter of the sexual irregularities of the artist, she believes, “can only in the end seriously damage our appreciation of the rich possibilities of art in general.”'

MacCarthy's book is impressive and enjoyable and does indeed give a good account of the 'multifaceted life of a multi-talented artist and an absorbingly interesting man'. I have no problems with the mention of sexual relations with Elizabeth and Petra which are unquestionably part of the story. But the book was sold vigorously and no doubt successfully on the basis of the scandals it revealed. That may have been the responsibility of the publisher but MacCarthy played this element up in her Introduction which has an atmosphere all its own and may well have been the only part most of of the reviewers bothered to read. The result is that, as she says, 'the fact of Gill’s abuse of his daughters has grown to become the thing that defines him.' I have no idea why the man who attacked Gill's statue or the people who have signed the 38 degrees petition have felt so strongly on the matter. It may well be that they themselves suffered some sort of abuse in their childhood and I can hardly blame them for their feelings confronted with the work of a man whom they know, simply and exclusively, as an abuser. The more so when the BBC's own 'culture editor' characterises him as 'a monster, a depraved paedophile who ... committed horrific sexual crimes'. But it also needs to be understood that different kinds of sexual activity can cover a wide variety of feelings and reactions on the part of both 'perpetrator' and 'victim' and that a blanket categorisation that would throw Eric Gill and his relations with his daughters (unquestionably very loving independently of the sexual side) into the same category as Jimmy Savile and his relations with his victims really doesn't contribute very much to our understanding of what it is to be human.