CONCLUSION: VENERATION AND [OR?] CONTEMPLATION

To conclude. The promise of the image of the Saint presented for veneration is that it helps us enter into a personal relationship with the Person (Saint, Christ, Mother of God) represented. The idea of 'likeness' is important (hence the importance of the stories of King Agbar and the icon not made by human hands, or of Saint Luke painting the Mother of God, by which the likeness of Christ or of the Mother of God is given authority). Since the icon in a manner of speaking IS the Person, we approach it as we would the Person, with awe, with lowered eyes. We do not paw over the painting with our eyes, delighting in the play of lines and colours even if, as may be the case, these may be rich and satisfying.

The rhythmic painting is approached in a quite different spirit. Here we are invited to look attentively, to enter into the play of lines and colours. The promise of the painting is that it opens up to the fulness of our human nature as it functions in space, time and ultimately (I would argue) Eternity. It is a mirror raised before us to remind us of the fulness of our human nature as the image of God. As such it too has a religious function.

Can these two religious functions be reconciled in a single work?

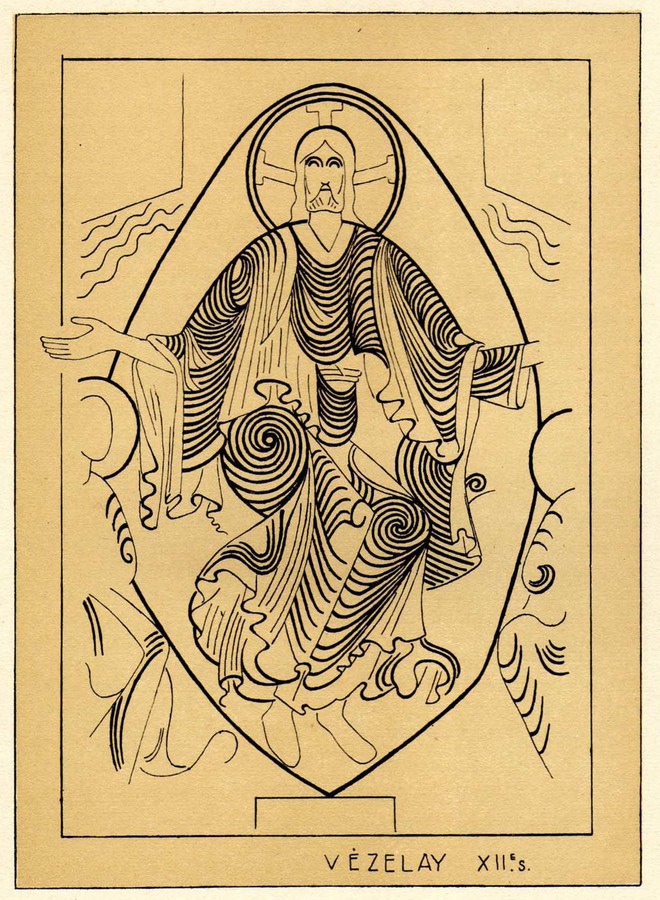

[Fig 13]: Illustration from Albert Gleizes: La Forme et l’Histoire, Jacques Povolozky, Paris, 1932, p. 19.

Figure 13 is a drawing based on the tympanum of the abbey church in Vézélay. It was prepared by Robert Pouyaud as an illustration to the book Form and History by Albert Gleizes. The drawing emphasises the rhythmic side of the tympanum, the element it shares with insular art (the book delights in ridiculing the argument of the specialist in Romanesque art Emile Male that the turbulence of Christ's garments was suggested by the rough wind that blows through that part of France). Is the Christ in the tympanum an object of veneration? Do we wish to engage in an act of veneration, or do we wish to stare at the whole movement of the tympanum, allowing it to raise us to an act of silent contemplation? I am not proposing an answer to this question, only suggesting that it is a question worth pondering.