THE CONTINUATION OF MOLY SABATA IN AMPUIS

My interest in Albert Gleizes and his school began in the 1960s when, still a teenager, I met the painter and poet, Gleizes's friend, Walter Firpo. In 1982, I realised that I had accidentally stumbled upon something of great importance, something that had to be taken up in earnest. I travelled to Paris to meet Firpo and he insisted that I go to Ampuis in the Rhone Valley, South of Vienne, South of Lyon, to meet Genevieve Dalban.

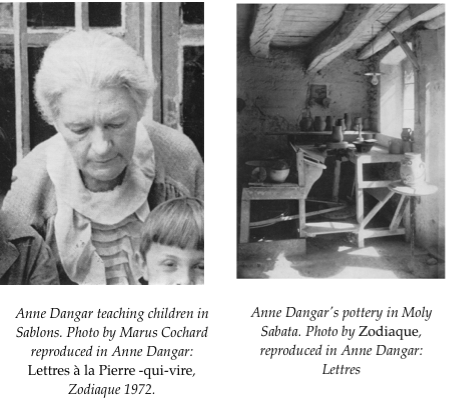

Genevieve Dalban as a young woman fresh from studying ceramics in the art college in Dijon - Genevieve de Cissey as she was then - had been told by the Lyon gallery owner, Marcel Michaud, that she had to meet Anne Dangar. Anne Dangar, however, had become somewhat wary of the young people sent to her by Marcel Michaud. 'I don't have time to waste with little girls who want to play with clay' she said, rather grimly, insisting that pottery could not be a hobby. It was a craft that demanded a long, difficult apprenticeship. Nonetheless she quickly saw that Genevieve's interest in her own work was genuine. But there was still a problem: 'I notice that Madamoiselle is very taken with the pottery but she hardly looks at the paintings.' Genevieve replied that she really didn't understand 'modern art'. Dangar then explained to her that the paintings - by Gleizes, Pouyaud and other members of the school - were based on exactly the same principles as the decoration of the pottery. People who thought they didn't understand non-representational painting were often perfectly able to appreciate the beauty of lines, shapes, colours, organised for their own sake, independent of a 'subject', when they encountered it in the applied arts.

Anne Dangar invited Genevieve to attend a two week painting course that was held in Moly in 1949. It was there that she got her basic instruction in the workings of 'translation-rotation' which she would later teach herself. After Anne Dangar's death she moved into Moly to help Dangar's companion, the weaver Lucie Deveyle. At the same time she underwent the same apprenticeship in pottery that Dangar herself had experienced, with Jean-Marie Paquaud in Roussillon. Subsequently she married Charles Dalban, a hi-fi specialist, and moved to his house in Ampuis where there was a large 'grange' which she and Charles converted into an exhibition space both for her own work and for the work of others working in the same line. When I arrived there were a number of important paintings by Gleizes from the collection of the art historian André Dubois in Lyon and of the publisher, Henri Viaud in the Jabron Valley, Alpes de Haute-Provence.

Genevieve received me together with André Dubois whom she had invited because she wasn't sure of my language skills and he had a little English. Not knowing very well how to introduce myself I bubbled with enthusiasm about Albert Gleizes and was a little put out when André, in his slow, lugubrious manner, said: "Je m'en fous de Gleizes." Genevieve later explained to me that what was important wasn't Gleizes the man, with all his little personal foibles and weaknesses - anyone who has read Anne Dangar's correspondence will be well aware of them - but the idea, the principles of the craft. To use one of Dangar's favourite expressions, Gleizes was the 'chosen vessel'. What was important wasn't the vessel but what the vessel contained. Whether or not this was what André had in mind it was certainly very much Genevieve's own approach.