CUBISM AND HIERATIC ART

It may be no coincidence that this transition from expressing a reservation concerning Beuron and hieratic art to outright hostility occurs in 1913, at the height of the controversy over Cubism - in fact at the moment when Cubism, universally mocked and reviled on its appearance in the public salons in 1910-11, is beginning to appear triumphant with something like it being adopted by increasing numbers of younger painters. Neither in his published writings nor in his journals of this period does Denis appear to take much notice of Cubism. He would undoubtedly have seen it as one of the exaggerations of ideas worked out by himself and his friends in the late nineteenth century. In a review of the Salon des Indépendants of 1908 Georges Braque and André Derain are reproached with disregarding nature: 'They are geometers. they triangulate the human body, above all the female body in which they wilfully emphasise a certain black triangle. Mr Braque, Mr Van Dongen, Mr Czobel, Mr Derain evidently don't care much for nature and regard Greco-Latin beauty with horror. They are too much inclined to forget that "the end of art is delectation". Gauguin and his Tahitians are a little responsible for this uglification of forms, these quadrangular feet with four notches. But Gauguin's exoticism had such a strong smell of nature about it ...' (8) In a brief reference in the Journal from about the time of his 1913 talk, he associates Cubism with German thought, complaining about the absence of God 'in the thought of the modern Germans ... of Cubism and of negro art, and who are bored. Everyone is amused, therefore bored.' (vol ii, p.150).

(8) Maurice Denis: 'Liberté épuisante et stérile', La Grande Revue, 10th April 1908, reproduced in Théories, p.233.

He continues on the subject of Germans (and this was written before the war):

'Let the Germans be wiped away [anéantis], that, with Kantianism, all the drugs, the whole philosophical, social, ethical flea market [camelote] of the Teutons should perish and I think a great renaissance is possible in the French order and following the ideas of Action Française. Yes, but what materialism, what pride will triumph with the new ideas. That vague religiosity which for many served as a chrysalis for faith, won't it disappear to give way to a pitiless feeling for the immediately tangible [le concret]? My art doesn't have enough breath in it to accomplish what I wanted, to uncover that lovely friendship [rapport] that, in all the ages of French art, brought together so well nobility of mind and the precise charm of the real.' (ibid, pp.167-8).

It should be said, given the reference to Action Française, that the 1913 talk on religious art begins with an assault on the central idea of Action Française, that French culture - religious art included - found its highest expression not in the Middle Ages but in the seventeenth century, the period of absolute monarchy.

But was Denis, addressing the Amis des cathédrales in December 1913 at all aware that in February 1913, Albert Gleizes had published his Cubism and Tradition, arguing that Cubism was a revival of the great constructive effort of the cathedral builders of the thirteenth century, an article which the historian Mark Antliff has interpreted as a contribution to a debate on French history occurring in the ranks of Action Francaise? (9)

(9) I discuss Antliff's thesis in my essay 'On "Cubism"' in context, accessible at http://www.peterbrooke.org.uk/a%26r/Du%20Cubisme/contents

Albert Gleizes: Chartres cathedral, 1912

In the 1929 journal entry quoted at the beginning of this Introduction, Denis says 'Sérusier liked to think that Cubism had come from him.' Sérusier's only possible ground for making that claim was the publication in 1905 of the Aesthetic of Beuron, shifting attention sharply away from the Impressionist/Neo-Impressionist/Fauve emphasis on colour to the Beuron emphasis not just on geometry but on an essentially rectilinear geometry. (10) It seems more than probable that this thought would have occurred to Denis at the height of the Cubist scandal in 1912-13 and that it would have reinforced his hostility to Beuron and to all things German. Much later, in his History of Religious Art (1939), discussing the stained glass artists Louis Barillet and Alexandre Cingria, he associates Cubism with hieratism:

'There are also the partisans of abstract art, the geometers, for whom the notion of sensibility that has been evoked so many times in the course of this book, has only very little value. These belong to the young generation formed, following us, in the anti-naturalist aesthetic. They have retained from the Impressionism and from our subjectivism of 1890 only liberty, or license in the representation of nature; a sort of Cubism that produces a new hieratism. What interests them is the objectivity of the work of art, the decorative expression ... the descriptive element will be subordinated to the demands of the colour: the drawing will be only "approximative - a pure geometrical line in two dimensions, without relief or perspective.' (pp.300-01)

(10) I defend Sérusier's much derided claim in my 'afterword' to Lenz: Aesthetic of Beuron.

Louis Barillet: Magnificat, window in the Eglise St Dominique, Paris, c1940

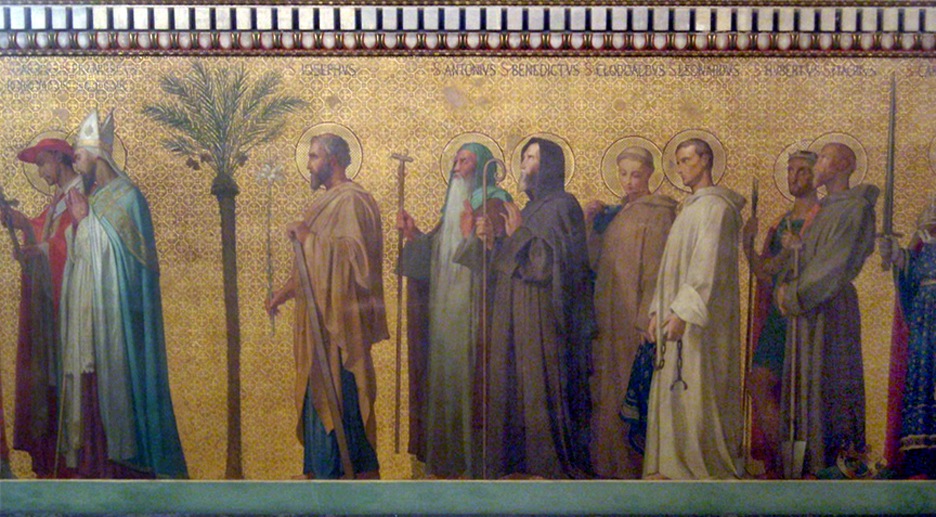

None of this implies a very radical reorientation in Denis's own tastes in painting, merely in the arguments he uses to defend them. From beginning to end of his career he remains faithful to Fra Angelico and the Italian primitives and, with regard to his immediate precursors in the nineteenth century, to Puvis de Chavannes and Odilon Redon. One could almost feel that Puvis was more important to him than Gauguin and his fellow 'Nabis'. His dislike of thoroughgoing naturalism, especially of the attempt to portray historical and biblical scenes realistically as if they were photographs of the real events, also remains constant. While condemning the idealised classicism of David and his school (associated as it was with the Revolution) he continues to have a soft spot for Ingres and his followers. Indeed, when we take the church decorations of Ingres' followers, notably Hyppolite Flandrin, and also Puvis into consideration we may wonder if, as far as Denis himself was concerned the tournant of post-Impressionism (Gauguin, Seurat, Cézanne) was as radical as he liked to believe. He toyed with the idea of a hieratic, 'objective' art, but he never really practiced it. One could be tempted to suggest that Denis finished with an essentially realistic art only using brighter colours than his pre-Impressionist forebears.

Hippolyte Flandrin: The Confessors. Mural painting in the Église Saint Vincent de Paul, Paris, 1848-54

(Photo taken from the very interesting account of Flandrin at https://stephengjertsongalleries.com/hippolyte-flandrin-1809-1864-a-nineteenth-century-master-part-i/)

In rejecting 'hieratism' and Byzantine art, Denis is also rejecting any idea of a genuinely 'sacred' art, that is to say, of the work of art as an object of veneration. He is not unaware of the problem but he sees it as a problem for the sculptor rather than the painter: 'a church can do without paintings, but not without statues. The piety of the faithful demands one for every object of devotion. It is certainly a disheartening problem for an artist to create a model that will be mass-produced, enlarged, shrunken, painted garishly, for use anywhere. It is quite another matter to translate into an original style attitudes, drapery, and expressions already fixed by tight conventions, to renew them without shocking the habits of the faithful, more demanding here than they are in matters of painting. To renew subjects such as Our Lady of Lourdes, Saint Anthony of Padua, the Sacred Heart, we lack a man of genius.' (Most Recent Developments). The sculptor is constrained by the expectations of the faithful; the painter, providing an edifying decoration is under no such constraint: 'I exclude nothing except that which is not art - or that which contains no expression.' We can see how far Denis is from the problem of the Orthodox icon which is an object of devotion and as such dependent on the good will of the devotee. This means observing certain conventions that the devotee, the faithful, can understand and recognise.

In the later pages of his journal, Denis sometimes expresses enthusiasm for the young Dominican, Marie-Alain Couturier ('How young he is! and how good!'). Following the passage given above in his History of Religious Art on the 'partisans of abstract art', he quotes 'Fr M.A.Couturier, young Dominican monk and avant garde painter' saying 'An art born entirely from the incarnation of the Word has nearly nothing to gain from the schematisms, the abstractions with which too many artists in our time confuse the spiritual.' In the aftermath of the war, Couturier and his fellow Dominican, Fr Pie Raymond Régamey, were responsible for the policy of employing the most prominent artists of the age - Matisse, Léger, Le Corbusier - to decorate churches, regardless of their own religious beliefs, giving them the largest possible freedom. Régamey talked of 'our present day taste for painting that would be like a cry.'

Earlier in this introduction I evoked the argument of Albert Gleizes that the great change that had begun in the late nineteenth century was the change (in the event, unrealised) from subject to object, from the subjective to the objective. In the end, having renounced the object, the 'flat surface covered in colours assembled in a certain order', the 'objective deformation', what Denis was proposing to the faithful in his Atelier d'Art Sacré, was the prospect of being surrounded in church by the subjective opinions of an artist, a 'man of genius'.

Peter Brooke

Summer 2