MEETING WITH JEAN COCTEAU

It would hardly be surprising if, as my first thesis suggests, Gleizes was a little disorientated and unsure where to go next. And it is in this state that, through Juliette Roche, who will soon become his wife, he meets Jean Cocteau. Juliette Roche Gleizes had known Cocteau since childhood – her father was Cocteau's godfather. She maintains that it was Gleizes who orientated the 'right wing' Cocteau, whose taste in painting had previously been conservative, towards the 'left wing' artistic avant garde. (4)

(4) Juliette Roche's description of the meeting between Gleizes and Cocteau can be found in Pierre Alibert: Gleizes – Biographie, Galerie Michèle Heyraud, Paris, 1990, pp.63-4. There is a similar account in Francis Steegmuller's Cocteau, a biography (Constable, 1986), pp.115-6 and David Cottingdon's Cubism in the Shadow of War, 1998, pp.192-3.

The period of Gleizes' closest collaboration with Cocteau sees the emergence of what we may call the 'theatrical' aspect of his character. The theatre had been Gleizes' first love, prior to painting. In 1905/6, he had, as secretary of the Literary and Artistic Section of the Association Ernest Renan, organised street theatre and poetry readings in working class areas of Paris; he had been responsible for an ambitious 'open day,' with a variety of spectacles, at the Abbaye de Créteil in 1907; he was enthusiastic about Cocteau's proposal for a production of Un Songe d'un nuit d'été [Midsummer night's dream], which would feature the clowns of the Cirque Medrano; when the war broke out, he would be charged with organising entertainments for the troops at the garrison in Toul.

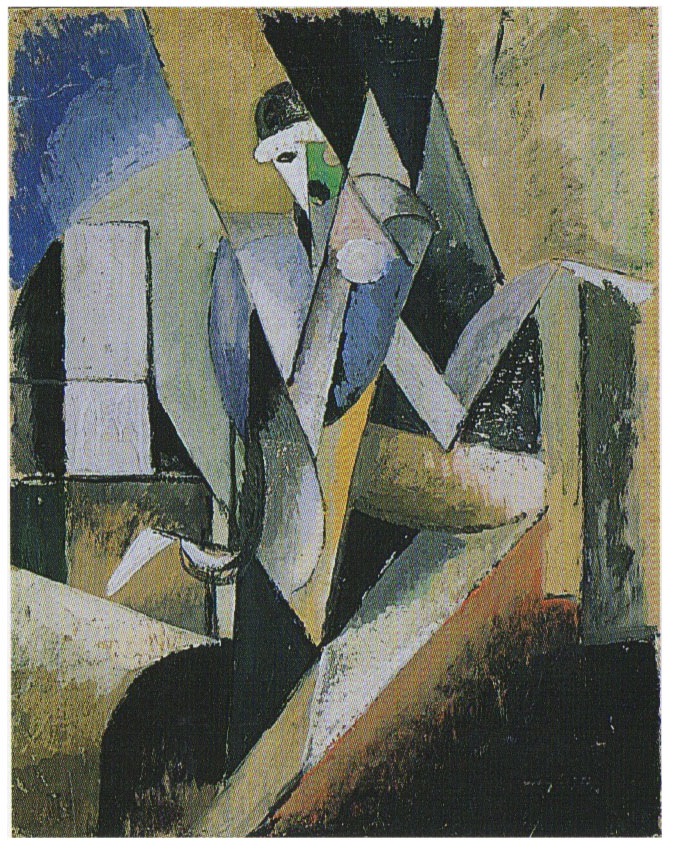

His painting of the time, including the portraits of Juliette Roche, of Cocteau and of Stravinsky, and the series begun (probably with Cocteau's play in mind) on circus themes, all seem to suggest a desire for lightness, gaiety and colour in contrast to the 'majesty' of the Cubist work. It is a real, straightforward lightness. His circus figures are presented simply and brutally without any of the literary symbolism and sentimentality that attaches to the Commedia dell'arte theme which would soon spread its baneful influence throughout most of the rest of the Cubist school.

Sur un thème de cirque, 1914

Gouache on cardboard, 67.3 x 52.7 cm

Present whereabouts unknown

THE PROBLEM OF THE PORTRAIT

So we can suggest that after the great 'epic' of the early days of Cubism, Gleizes wants to relax a little. At the same time, the period between 1913 (Portrait de l'éditeur Figuière) and 1915 (Portrait de Florent Schmitt – Chant de Guerre) sees an intense, apparently very serious and deliberate, research into the possibilities of the portrait. This research is a little story in itself which would repay a detailed study. Here I can only offer some general remarks.

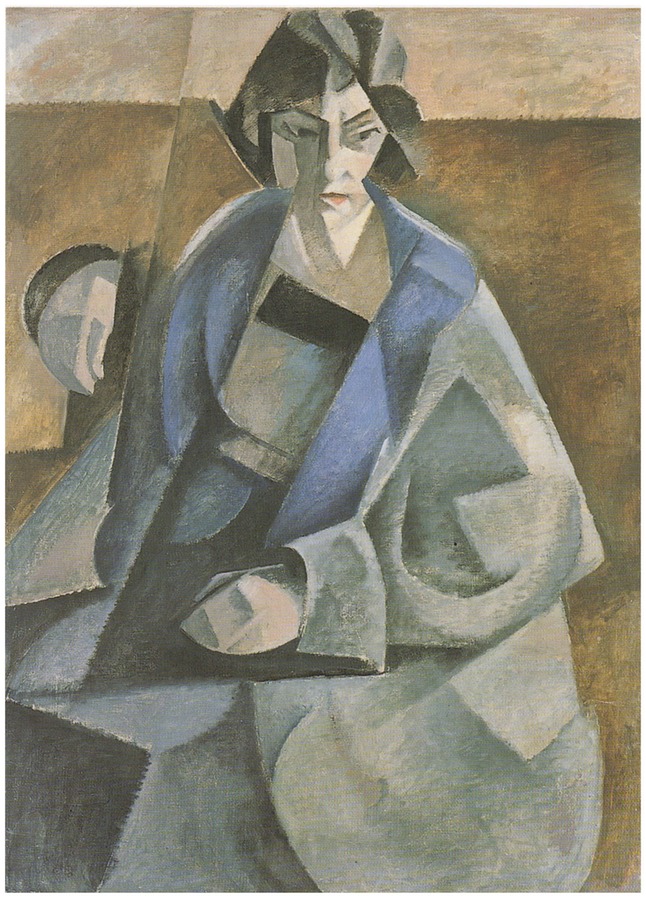

1912? [Woman in a blue coat]

Oil on canvas, 100.2 x 73.5 cm

Not signed or dated (but I feel pretty confident it's him!)

Johannesburg Art Gallery

Portrait d'un médecin militaire, 1915 (though signed and dated 1914)

Oil on canvas, 120 x 95 cm

New York, Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum

The problem is to show the subject's face in movement, from several different angles, and to reconstitute it on a flat surface in a way that would still appear logical and even 'normal' – that would not appear to be monstrous. This is the 'total image' that Gleizes' close friend, Jean Metzinger, had evoked in an article written in 1910 which Gleizes often quotes when talking about this period. (5) We may note that in general throughout his whole career Gleizes is very reluctant to distort or rearrange either the human face or body. To the disgust of some of the critics, seeing that in this respect he is less radical than Picasso, the figures in Le Dépiquage des Moissons, Joueurs de Football, L'Homme au Balcon remain conventional. The head is on the shoulders, the body is on the legs. (6) The Portrait d'Eugène Figuière is beginning to show something of the 'monstrous' character Gleizes is anxious to avoid. But with the Florent Schmitt – Chant de Guerre or the Médecin Militaire Gleizes seems to have solved the problem. These are distinctly portraits and there is nothing about them that is bizarre or monstrous, yet all conventional representational indications have been abandoned and replaced by means that are purely pictorial and expressive of the movement of the subject (the movement of Schmitt, the composer, conducting his oratorio, Chant de Guerre; and the massive, tragic stillness of the doctor in the military hospital at Toul, Gleizes' superior (who commissioned the portrait but was somewhat dismayed by the result), Dr Lambert.

(5) Note sur la peinture. There is an English translation in the Du "Cubisme" section of the present website.

(6) For example Edward Fry's account of L'Homme au balcon in his Cubism, 1966, p.26. It may be noted that for all the breaking up of conventional external appearances neither Picasso nor Braque do much to change the normal order in which human figures present themselves. This is especially true with regard to faces. The portraits of Uhde and Kahnweiler remain quite conventional in the midst of a halo of broken lines and angles.

But what is surprising is that, having achieved these means which seem so full of possibilities, Gleizes abandons this line of research and will never go back to it. He never again seriously turns to portraiture (the second Portrait de Jacques Nayral of 1917 is the development of drawings prepared, immediately upon learning of his friend and brother-in-law's death at the beginning of the war, in 1914).

I should add here (as I didn't in the original published article) that this period also saw an intense exploration of the means offered by the landscape, in particular the landscape round where he was stationed near Toul. Like the portraits, they deserve a separate study.

THE WAR

The war of course marked a considerable upheaval in Gleizes' life. It saw the end of the long period in which he had been living peacefully in his parents' house. Thereafter he seems to have had surprisingly little contact with his family. And of course it saw the breaking up of both the main circles – the Cubist circle and the more literary circle of the Abbaye de Créteil – in which he had been moving in Paris.

Nonetheless, compared to Léger and Braque who were both sent to the front, Gleizes was lucky with regard to the war. The officer who received him at the garrison of Toul was, improbably enough, interested in Cubist painting and he gave Gleizes, together with other artists and musicians, the responsibility for organising entertainments for the troops. (7) It was a job for which, as we have seen, Gleizes was better qualified than might have been expected of the most earnest, most 'majestic' of the Cubist painters. In this context he was able to continue his painting on a small scale. The Portrait d'un Médecin Militaire is his only full-scale oil painting from the period, but a number of important works were executed later in New York on the basis of drawings and gouaches which had been done in Toul.

(7) The officer in question was Raymond Vaufrey who was later to become well known as an anthropologist.

But if Gleizes had an easy time of it, the war had still upset him deeply. In a talk given in New York soon after his arrival in 1915 he describes his horror at the war fever that surrounded him, his disgust at the way the Germans were characterised in war propaganda, and at the way the vulnerability of the young men herded into the garrison was exploited by those who were responsible for their wellbeing. (8) The sense of moral outrage at the murderous folly of the war and the conviction that his own country was as much to blame for prolonging it as anyone else, would remain with him all his life. It helps to explain at once his involvement with the Communists in the 1920s and his refusal to condemn Hitler (on the grounds that he was the inevitable consequence of French and British policy) in the 1930s.

(8) 'Conférence faite au Twillight [sic] Club de New York, November 1915', unpublished ms which was part of the Viaud Archive in Aubard, now dispersed. I possess a photocopy.