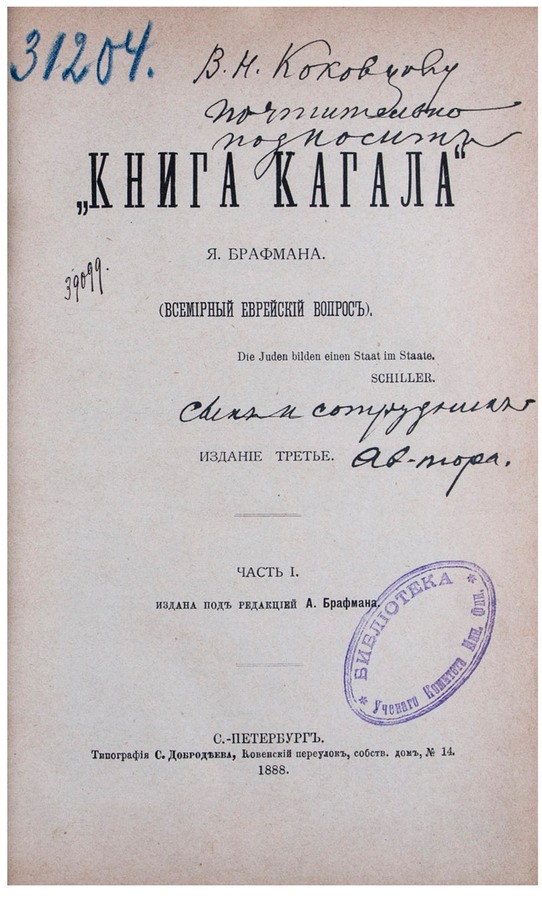

Book of the Kahal, 1888 ed. Signed and inscribed by Brafman's son.

IAKOV BRAFMAN AND THE RUSSIAN VIEW OF JEWISH HISTORY

The period also saw the development, mainly in St Petersburg, of what might be called, if it isn't a contradiction in terms, a philosophical antisemitism. Dostoyevsky's essay on The Jewish Question, published in 1877, and the response of Konstantin Pobedonostsev in 1877, which I referred to in the last article, could be taken as examples. They both saw the Jews as representing capitalism and the associated Western European liberal and secularising philosophy. To quote Pobedonostsev: 'they embody the spirit of the century.' (4)

(4) It may be worth mentioning though that Jews barely feature in Dostoyevsky's novels.

The argument that the Jews were a malign force not just in the particular circumstances of the Russian Empire but in the world generally was reinforced by the publication in 1869 of Iakov Brafman's Book of the Kahal. Klier (Imperial Russia's Jewish question, p.281) calls this 'the most successful and influential work of Judeophobia in Russian history' which, given the competition provided by The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, seems a large claim. Brafman was a Jewish convert to Orthodoxy who, coming from a very poor background with no, or very little, education, had become a teacher of Hebrew in the Russian Orthodox seminary in Minsk. In 1866 he had obtained leave of absence to go to Vilnius, capital of Lithuania, where he presented himself as a missionary to the Jews. In the Vilenskii Vestnik, the official publication of the North Western Educational District, he published an article arguing that the problem with Jewish culture did not lie with the Talmud as such but with the 'Talmudic Kingdom', a system of social organisation which allowed a Jewish elite to exercise control over every aspect of the lives of the Jewish masses and which, he claimed, had been reinforced by Polish and Russian government policy.

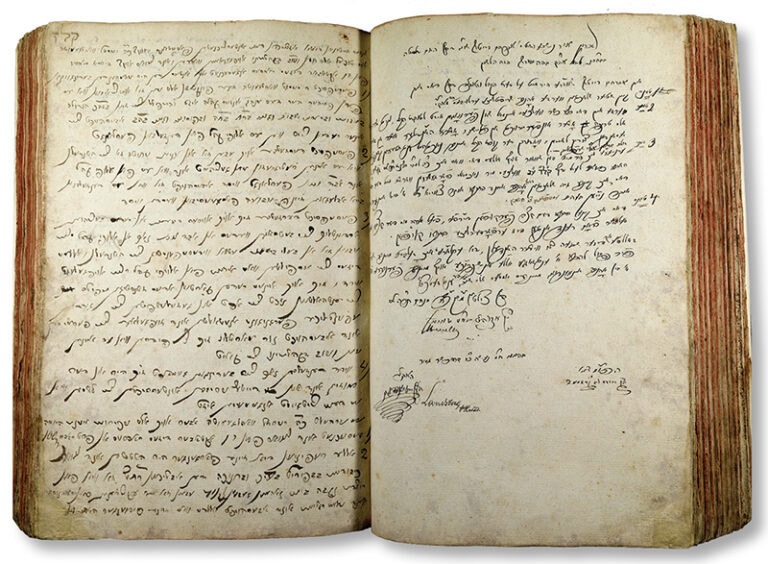

Through the director of the North West Educational District, I.P.Kornilov, he obtained a government stipend to translate Jewish texts which he claimed would prove his case. These were the 'pinkas', the communal record book of the Kahal of Minsk from 1794 to 1833. Unlike the Protocols, these were genuine texts though initially, from 1867 to 1869, very poorly translated and edited. The 1869 version contained 285 documents. A much more scholarly Russian edition was published by the Imperial Geographic Society in 1875, with 1,055 documents.

A page from the Zülz Pinkas, 1796 to 1805. (From the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, National Library of Israel.)

The 1869 edition contained a commentary by Brafman which gave his version of Jewish history. He claimed that the Kahal, as an institution governing the whole of the Jewish world, had been formed after the destruction of the temple of Jerusalem in order to discipline and regulate Jewish life. It was the Kahal that commissioned the Talmud, creating a bewildering set of regulations that could only be understood and interpreted by an elite. The Kahal took responsibility for every aspect of Jewish life - the rules for the slaughter of animals for example gave it control over the supply of food. The main intention was to keep Jews separate from the societies in which they lived. To this end they established their own legal system in disrespect of the gentile system. Perjury was permitted in the gentile courts - it could be forgiven on the Day of Atonement. The Kahal could regulate competition among Jews by giving particular Jews a right of monopoly to exploit particular gentiles. He quoted the Talmud to the effect that gentile property was an empty lake into which Jews had the right freely to cast their nets.

He outlined five new Jewish brotherhoods which had taken on the Kahal's role of controlling international Jewry. They included the St Petersburg based 'Society for the Spread of Enlightenment among the Jews' recently established by the banker Evzel Gintsburg but also, and chiefly, the Paris based Alliance Israélite Universelle, which had come into existence in 1860 and was a favourite target for anti-semitic theorists. Klier (p.291) describes Brafman's account of the Alliance as 'an accurate, if critical, summary of its goals and objectives.' and says that the whole argument was much more credible than most of the contemporary European anti-semitic fantasies.

Brafman attracted widespread Russian support, including from the journals Kievlanin and the St Petersburg based Golos ('The Voice') but was subjected to withering criticism by Jewish intellectuals in Den' ('The Day') and Novoe Vremia (New Times). In 1870, Brafman was appointed Censor of Jewish books in the Chief Office for Press Affairs in St Petersburg, where he died in 1879. His work was continued by his son, Alexander, developing the argument that the Alliance Universelle was aiming not just at establishing domination over Jews but over the world as a whole.