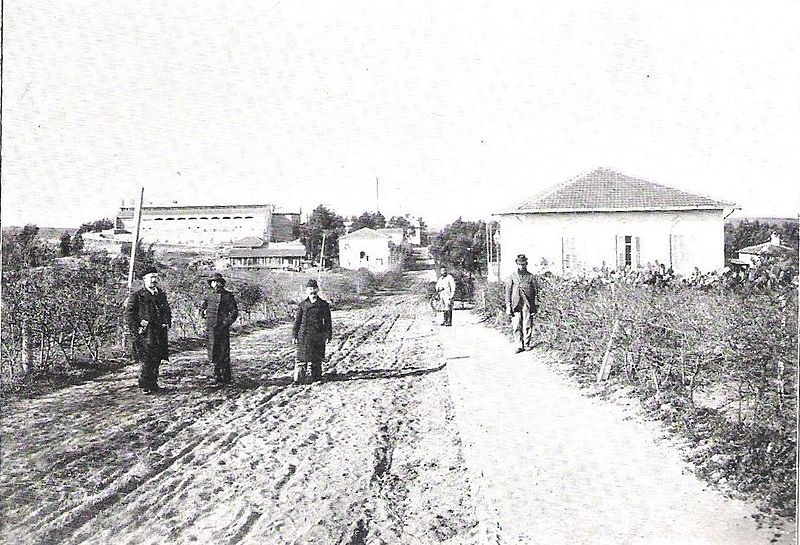

Rishon le Zion in 1899

BILU AND THE FIRST ALIYAH

At the beginning of 1882 the Jewish establishment responded to the pogroms in the traditional manner by proclaiming days of fasting and prayer (Frankel, p.90). The occasion was marked by a demonstration of Jewish students attending Russian language universities. This was a major phenomenon of the time. According to Frankel (p.120) there were 247 Jewish students in the Russian language universities in 1876, 1,856 in 1886. It paralleled in an interesting way the figures he gives for the involvement of Jews in the revolutionary movements, at least as recorded by the Okhrana, the Russian secret police - 63 Jews out of 1,054 identified in the period 1873-7; 579 out of 4,307 in the period from 1884 to 1890.

There had been an assumption that the involvement with the Russian universities would necessarily alienate them from the Jewish world: 'The spectacle of the returning sons therefore aroused widespread wonderment.' On the days of fasting and prayer 'the students appeared in the synagogues not in pairs but en masse to express symbolically their solidarity with the Jewish people in a time of trial ... In their military type uniforms the mass of students and gimnazitsky stood out clearly in the synagogues which were crowded beyond capacity for the occasion.' (p.90)

But this was not just an expression of solidarity. It was also an expression of defiance against the traditional Jewish passivity in the face of persecution, the tradition represented by the day of prayer and fasting, an expression of repentance for the sins which God had punished by unleashing the pogroms. In Kiev 'the presence of the students in the synagogue, their sincere, warm and yet fiery speeches, the poems - brought tens of thousands of Jews to the synagogues and for lack of space people had to stand in the street ... The police could not help noticing of course ... and the governor general called in the rabbi and rebuked the censor for permitting the poems to be printed." (Frankel p.91, quoting a letter addressed to the pioneer Social Democrat Pavel Akelrod).

Among the students involved were the founders of 'Bilu' - fourteen students at Kharkov University who met on the day after the demonstration and were throughly devoted to the idea of emigration to Palestine - 'Bilu' was an acronym based on the Hebrew of Isaiah 2:5, 'Let the House of Jacob go' (not quite how it is understood by the King James Bible: 'O House of Jacob, come ye and let us walk in the light of the lord.') Two of them, Moshe Yitshak Mints and Yaakov Berliavsky, went to Constantinople in May to meet Oliphant. But that was the month in which the Turkish government refused to open Palestine to Jewish emigration. Nonetheless other members of the group led by Yisrael Belkind went to Palestine in June and began a process of adaptation to the land in the agricultural school at Mikve Yisrael:

'"The director, Mr Hirsch," Belkind wrote in November, "who at first regarded Russian Jews in an unfriendly way and as incapable of working under the sun ... is [now] convinced that we do not lag behind the Arabs and to some extent even surpass them." (They were paid one franc a day for their labour.) "Our ultimate goal ... ," Vladimir Dubnow wrote to his brother Shimen [the Simon Dubnow we encountered in the last two articles - PB] on 20 October, "is, with time, to gain Palestine and return to the Jews that political independence which they lost two thousand years ago. Do not laugh [Simon Dubnow was indeed sceptical about the Zionist project - PB]. It is not a chimera."' (Frankel, p. 97, lacunae as in the original)

This was the group that formed the first agricultural colony of the aliyah, Rishon Le-Zion. Although Rishon Le-Zion now claims to be the fourth largest city in 'Israel' (Wikipedia) its beginnings weren't very auspicious. It was dependent on outside help. The story is given by Frankel:

'The first important breakthrough came when an emissary from Rishon Le-Zion succeeded in October 1882 in gaining access to, and winning the sympathy of, Baron Edmund de Rothschild in Paris. Rothschild's decision to make an initial grant of 25,000 francs to that colony - in particular to six of the founding families that were left without any means - proved to be the beginning of a lifetime involvement in the cause of Palestinian settlement. He not only invested increasingly large sums in buying land, developing vineyards, building houses, and supplying livestock and equipment but also sent out overseers and agronomists to ensure that modern methods of farming be introduced. By the late 1880s, all the settlements (except Gedera) were receiving capital investments from him: Rishon Le-Zion, Zikhrov Yaakov, Rosh PIna, Petah Tikva, Ekron, Yesud Ha-Maala and Wadi Hanin (Nes Ziona).' (p.115)

Rothschild's support, however, was, as the mentioned exception of Gedera indicates, problematic:

'Baron Edmund de Rothschild had very definite ideas about what could and could not be permitted in the new colonies. He had a romantic image of small scale farmers, simple people devoted to orthodox religious practice, dressed in Arabic or Turkish style. The supervisors whom he put in charge of the colonies were expected to keep tight control over all aspects of life there.

'Rothschild's conception could not be reconciled with that of the Biluim, who (although for the most part not socialists) were convinced that their duty was to act as the core of a modern, secular, and political movement ... In 1883, Yisrael Belkind, who had settled with other Biluim in Rishon Le-Zion and had clashed with the overseers there, left it rather than have Rothschild cut off funds from the entire colony. In 1887 this pattern repeated itself. In this case, the decision by the overseer (Ossovetsky, a young Russian Jew recruited by Netter at Brody in 1882) to expel the leader of the day labourers in Rishon Le-Zion (Mikhael Helperin) led to a bitter clash with the entire colony ... Rothschild and his staff in Paris were convinced that they were faced by a form of Russian nihilism ... If it had not been for the combined efforts of Pinsker, Pines and Lilienblum [leaders of the Palestinophile movement in Russia - PB] the Biluim could not have remained as a group in Palestine ... For his part, Pinsker was able to channel funds periodically to Gedera, the settlement of the Bilu that was boycotted by Rothschild. But even in Gedera the few remaining Biluim were not free to live as they chose. Religious zealots in Jerusalem reported back to Russia that they were free-thinkers and so turned the leading rabbis in the Palestinophile movement ... against them.' As a result Pinsker 'wrote to the group in Gedera appealing to them to maintain voluntarily the traditional religious observances for the sake of the general cause ... Pinsker's letter had its effect. Most of the small group in Gedera, ranging between one and two dozen, agreed, as Pines reported, to take on "the yoke of the Torah"' (pp.126-7).