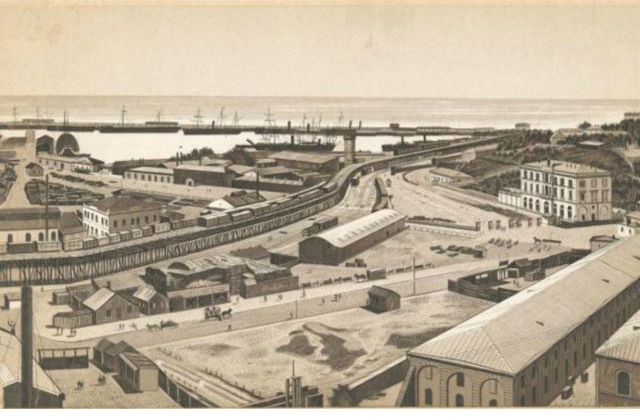

The Port area of Odessa

THE 'LOYALISTS'

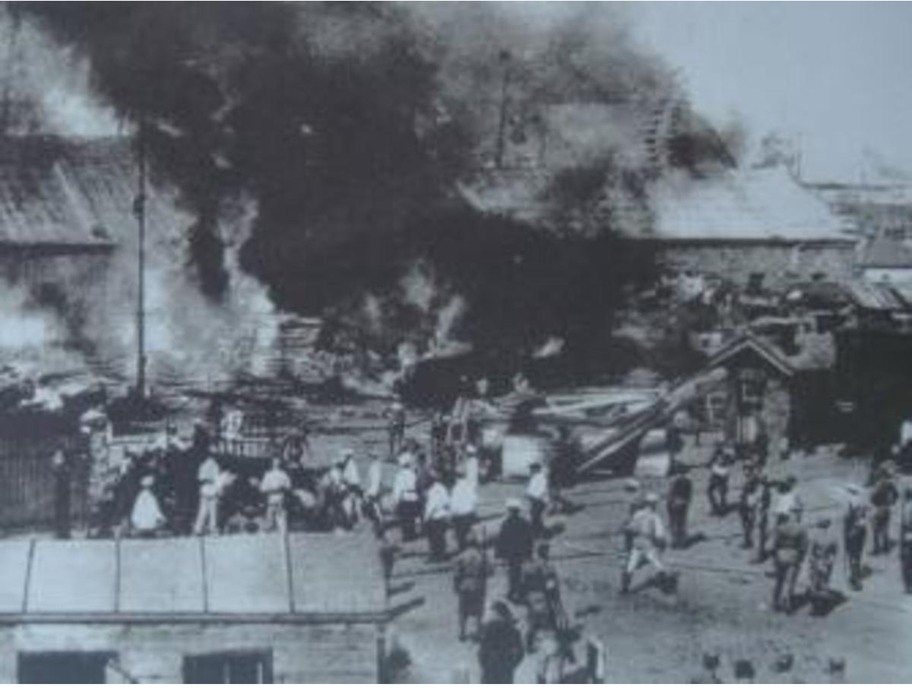

Weinberg's account of what then happened is horrifying. He says that the most prominent element in the pogroms were the day labourers working in the port and he goes on to describe their conditions of life. In order to get work day by day, they had to put their names on a sub-contractor's list which meant getting up at two or three o'clock in the morning. If they succeeded in getting work they often had to wait in an inn until 10.30 at night to get their money. A third of their wage went to the sub-contractor. Many of them were living for years on end in terrible conditions in dosshouses. Not only were they in competition with Jews for what work there was but 'the domination of the grain trade by Jewish merchants predisposed many dock workers against the Jews whom they conveniently saw as the source of the troubles, particularly the lack of jobs ...' The conditions of their lives predisposed them to drunkenness and hopeless rage. In June, in the events surrounding the arrival of the Battleship Potemkin, 'dockworkers and day labourers exploded in a fit of wanton rage but chose to challenge the authorities by destroying the harbour,' not, on that occasion, attacking the Jews.

The port on fire during the confrontation over the Battleship Potemkin

Weinberg says of the Loyalist demonstration: 'This demonstration had the earmarks of a rally organised by extreme right-wing political organisations like the Black Hundred, which had emerged earlier in the year.' This suggests that there was an organisation called the Black Hundreds, one among several. 'Black Hundreds' seems to have been a general terms applied to anti-semitic and anti-liberal agitators and to the people who engaged in the pogroms, but the extent to which this was an organised activity - still less an activity organised or promoted by the central government, as widely believed - is very dubious. Hans Rogger, who has been quoted in earlier articles arguing against the idea that the pogroms were willed by the government, says that, prior to 1905:

'traditional conservatism ... had tended to shun political action and to consider it either a prerogative of the state or the illegal activity of liberals and socialists. The post-1905 Right was more militant, more demagogic, more intransigent vis-a-vis the state and its officials than conservatives either wished or dared to be. In this period, traditional conservatism was characterised by intellectual poverty and an unwillingness to descend into the political arena. These characteristics stemmed not only from a distaste for politics and a reluctance to see the larger public become involved in it, not alone from the belief that the historic interests of the nation would best be protected by established institutions and their servants, but also from the genuinely conservative inclination not to bestir oneself, to leave things as they were, to let them take their course and hope that in time they would come out all right.' (4)

(4) Hans Rogger: 'Was There a Russian Fascism? The Union of Russian People', The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Dec., 1964), p.398.

Owing to the success of the liberal revolution of 1905, crowned by the October Manifesto, however, 'some way had to be found for supporters of the status quo to demonstrate that popular sentiment was not all on the side of the opposition and that the state could count on allies in society if only it would resist the headlong rush to concession and innovation.' But 'The efforts made in this direction before October 1905 - the staging or encouraging of pogroms and the organisation of a number of monarchist organisations, mostly of local scope, were not notably successful. They failed to transform sporadic outbursts of popular passion or dynastic loyalty into sustained or organised political action; they were uncertain of their aims in the face of the government's own uncertainty, and they did not prevent the issuance of the October Manifesto which, with its promise of civil liberties, political rights, and a popularly elected legislative duma, made it all the more necessary that conservatives abandon their self-imposed restraint and bring a broadly based movement into the field against the liberals and radicals who had organised themselves into political parties long before October 1905.' (5)

(5) In fact it was only in October that the Constitutional Democratic Party was formed, though it was preceded in July 1903 by the conspiratorial Union of Liberation which was the main political driving force of the events of 1905. See Shmuel Galai: The Liberation Movement in Russia, 1900-1905, Cambridge University Press, 1973.

He is explaining the formation of the 'Union of the Russian People', established on October 22nd 1905 (not, as claimed by Walter Laqueur, March 1906 (6) - the month, as it happens, of the formation of the first Duma, created as a result of the October Manifesto). The term 'Black Hundred', according to Podbolotov (p.194), 'came from mediaeval Russia, where it signified the lower class which stayed outside the town walls. Although violent and mutinous' they 'were conservative by virtue of their illiteracy and supposedly unquestioningly supported the autocracy and "the established traditions." At the beginning of the twentieth century the opponents of the autocracy nicknamed, disdainfully, the monarchists Black Hundreds because of their supposed "backwardness" and "proneness to violence"' The populist URP, whose programme included redistribution of land to the peasantry and legally regulated employer-employee relations, (7) 'willingly accepted this nickname as they claimed to be representatives of the "Black millions" of simple, silent-majority Russians.'

(6) Walter Laqueur: Black Hundred - the rise of the extreme right in Russia, New York, HarperPerennial, 1994, p.18.

(7) They also seem to have had an understanding of Modern Money Theory. According to Rogger (p.411): 'There were denunciations of the government's financial conservatism; demands for easy credit and a paper ruble not backed by gold - "for the issue of paper notes depends on the will of the Tsar and the needs of the people"'

The appearance of this organised political anti-semitism did not result in an increase in political violence. On the contrary, whatever might have been the ambitions of its founders or its members, it coincided with the decline in political violence that accompanied the tough security measures and economic reforms introduced by Pyotr Stolypin after his appointment as Interior Minister (April 1906) and Prime Minister (July 1906).

... AND ZIONIST RADICALISM

But from the point of view of understanding the shape of Jewish politics in Palestine, it is the intellectual and political development of the Jews in the Russian Empire, not their opponents, that counts. Here there are two figures that seem to me to be of particular interest - Ber Borochov and Vladimir Jabotinsky. Borochov was the theorist of the Jewish Social Democratic and Labour Party - Poale Zion (ESDRP-PZ). Frankel (p.330) says of him: 'He himself died in Kiev in December 1917, following a short illness, at the age of thirty six. But his followers and comrades from the Poale Zion party became dominant figures in the Yishuv, rising with successor organisations, Ahdut Ha-Avoda and Mapai. Yitshak Ben Zvi, the second President of the State of Israel, and Zalman Rubashev (Shazar), the third President, had been among Borochov's closest personal associates in the Russian party in its year of formation, 1906. Three Prime Ministers of Israel (David Ben Gurion, Moshe Sharett and Golda Meir) were also veteran party members although not personally identified with Borochov. His works have been republished in numerous editions in many languages ... Streets and city quarters have been called after him in Israel.'

If Borochov was the founder of the Labour Zionism that dominated Israel in the early years of its formation, Jabotinsky was the founder of the 'Revisionist' Zionist tradition to which the opponents of Labour Zionism, Menachem Begin, Yitshak Shamir and Benjamin Netanyahu claimed to belong. Both men have an interest that is independent of their political influence - Borochov as a Marxist philosopher belonging to the camp of Lenin's main Bolshevik rival, Alexander Bogdanov, and Jabotinsky as a playwright, poet and novelist, author of the extraordinary novel The Five - an account of the differing fates of five children in a Jewish family in Odessa about the time of the 1905 revolution. They deserve an article to themselves.