TARAS SHEVCHENKO

What was left as distinctively Ukrainian was the language of the peasantry and of the oral folk tradition. Danylenko and Naienko call it the 'new literary Ukrainian', pioneered as such by Kotliarevsky. This was the language that was to be seen later in the century as dangerous, at first by literary critics, notably the best known literary critic of the 1840s, Vissarion Belinsky. A key figure in this development was the 'Ukrainian national poet', Taras Shevchenko.

Shevchenko was born in 1814 as a serf. He became personal valet to his master who recognised and tried to develop his talents as a painter, taking him first to Warsaw then, after the Polish rebellion of 1830, to St Petersburg. There his talent was recognised by the Russian poet, Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky, tutor to the Empress, Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas I, and to the heir apparent, the future Alexander II. On the initiative of the Empress, a raffle was held to buy him out of serfdom, enabling him to become a pupil of the painter Karl Briulov whose painting The Last Day of Pompeii had created a sensation, widely regarded as the first Russian masterpiece, in 1834 (Gogol wrote an essay in praise of it). In 1840, while still in St Petersburg, Shevchenko published his first collection of poems - Kobzar. Written in the native language it was hugely successful in Ukraine where he made 'an almost triumphal return of one who had left his native village in the corduroy of a page boy.' (17)

(17) Ivan Franko: 'Taras Shevchenko', The Slavonic Review, Vol.3, No.7 (June 1924), p.113. Franko was a leading Ukrainian writer, poet and political theorist, in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century. An oblast in modern Ukraine - Ivano-Frankivsk - is named after him.

He obtained a post in the Archaeological Commission in Kiev. 'Here he found himself surrounded by the younger generation which had already, certainly under the influence of his poetry, formed a secret society under the name of the "Brotherhood of St Cyril and Methodius" with the clearly expressed aim of educating the people and abolishing serfdom.' (Franko, p.113)

The most important of Shevchenko's poems from the point of view of Ukrainian nationalism was probably Haidamaky, his celebration of the last of the great risings against the Poles, the Koliivshchyna rebellion of 1768. According to George Grabowicz, President of the Shevchenko Scientific Society in the US: 'Discussions and polemics around the poem, especially by Polish and in time more so by Ukrainian critics, continued well into the 20th century and ultimately marked out the canonic Ukrainian perpective on Shevchenko; in effect Haidamaky became his best known, most often cited and defining work, that which made Shevchenko Shevchenko.' (18)

(18) George G.Grabowicz: 'Taras Shevchenko - the making of the national poet', Revue des études slaves, Vol.85, No.3, Taras Ševčenko (1814-1861) Création culturelle et conscience nationale (2014), p.425.

It's hardly surprising that Polish critics should have taken an interest in it since the Koliivshchyna rebellion was after all a massacre of Poles. The poem comes in fourteen parts and I've only been able to read six of them in translation (19) so this account will be very incomplete but the main theme, here as in many other of Shevchenko's poems, is nostalgia for a past when Cossacks were free and self-governing and there was no serfdom, together with regret that this past glory is forgotten by a weak and servile generation.

(19) Accessible at https://taras-shevchenko.storinka.org/taras-shevchenko-poem-haidamaki-english-translation-by-john-weir.html

And yet the glory in question is the glory of massacring Polish Catholics, described with great verve but also occasional notes of regret:

In Cossack graves our grand-dads lie,

Their grave mounds dot the plain.

What of it that the mounds are high?

Nobody knows they’re there,

Or whose the bones that ’neath them lie,

Nobody sheds a tear.

As it blows through, the wind alone

A gentle greeting says,

The dew alone at break of dawn

With tender teardrops laves.

The sun then turns its rays on them,

It dries and makes them warm;

Their grandsons? Oh, they’re not concerned -

For lords they’re growing com!

They’re numerous, but ask if one

Knows where is Gonta’s grave -

Where did the tortured martyr's bones

His faithful comrades lay?

Where’s Zaliznyak, that splendid soul,

Where sleeps that manly heart?

It’s hard to bear! The hangman rules,

While they forgotten are.

A long, long time the clamour dread

Resounded through Ukraine,

A long, long time the blood ran red

In streams across the plains.

O’er all the earth it cast a pall;

This horror day and night

Was ghastly, yet when we recall

Those deeds, the heart is light.

The climax of the poem comes when Gonta, the Cossack leader, finds himself obliged to kill his young sons because they admit to being Catholic:

From Kiev to Uman the dead

In heaping piles were laid.

The Haidamaki on Uman

Like heavy clouds converge

At midnight. Ere the night is done

The whole town is submerged.

The Haidamaki take the town

With shouts: "The Poles shall pay!"

Dragoons are downed, their bodies roll

Around the market-place;

The ill, the cripples, children too,

All die, no one is spared.

Wild cries and screams. 'Mid streams of blood

Stands Gonta on the square

With Zaliznyak together, they

Urge on the rebel band:

"Good work, stout lads! There, that's the way

To punish them, the damned!"

And then the rebels brought to him

A Jesuit, a monk,

With two young boys. "Look, Gonta, look!

These youngsters are your sons!

They're Catholics: since you kill all,

Can you leave them alone?

Why are you waiting? Kill them now,

Before your sons are grown,

For if you don't, when they grow up

They'll find you and they'll kill...."

"Cut the cur's throat! As for the pups,

I'll finish them myself.

Let the assembly be convened.

Confess — you're Catholics!"

"We're Catholics.... Our mother made...."

"Be silent! Close your lips!

Oh God! I know!" The Cossacks stood

Assembled in the square.

"My sons are Catholics.... I vowed

No Catholic to spare.

Esteemed assembly!... That there should

Be no doubt anywhere,

No talk that I don't keep my word,

Or that I spare my own....

My sons, my sons! Why are you small?

My sons, why aren't you grown?

Why aren't you with us killing Poles?"

"We will, we'll kill them, dad!"

"You never will! You never will!

Your mother's soul be damned,

That thrice-accursed Catholic,

The bitch that gave you birth!

She should have drowned you ere you saw

The light of day on earth!

As Catholics you'd not have died —

The sin would smaller be;

Such woe, my sons, today is mine

As cannot be conceived!

My children, kiss me, for not I

Am killing you today —

It is my oath!"

He flashed his knife

And the two lads were slain.

They fell to earth, still bubbling words:

"O dad! We are not Poles!

We ... we...." And then they spoke no more,

Their bodies growing cold.

"Perhaps they should be buried, what?"

"No need! They're Catholic ...'

Gonta does in fact, secretly and sorrowfully, bury his sons, still cursing their mother.

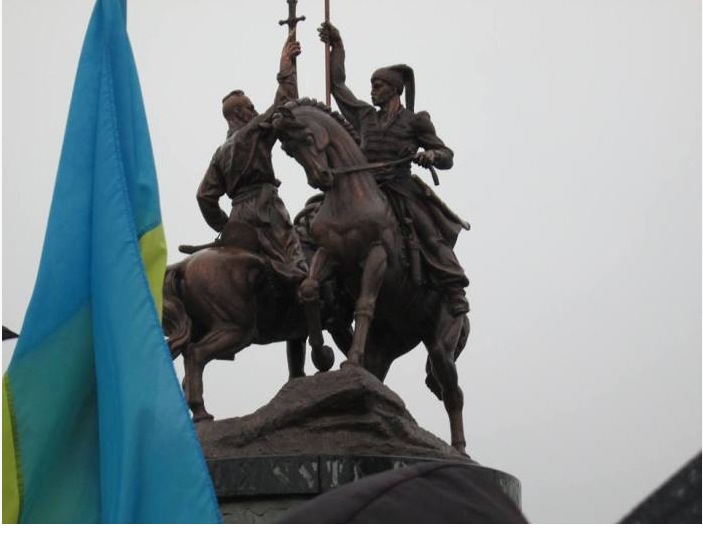

Monument to Gonta and Zaliznyak in, of all places, Uman

If Haidamaky does occasionally express regret that Slavs should be killing each other ('The heart is sore when you reflect/That sons of Slavs like beasts/Got drunk with blood. Who was to blame?/ The Jesuits, the priests!') there is no such regret in another, much shorter poem, The Night of Taras:

Before the dawn a slaughtered host

Upon the meadow lies.

"Like a red, twisting serpent,

The Alta bears the news,

To bid the ravens of the fields

A feast of Poles to use.

Black ravens to that noble meal

Came flying, ranks on ranks;

While the assembled

Cossack troops

Gave the Almighty thanks.

The ravens screamed, and plucked and ate

The corpses' eyeballs bright,

While the bold Cossacks raised a song

To celebrate that night,

That sombre night that dripped with blood

In bringing glory deep

To Taras and his Cossack troop,

While Poles were lulled to sleep. (20)