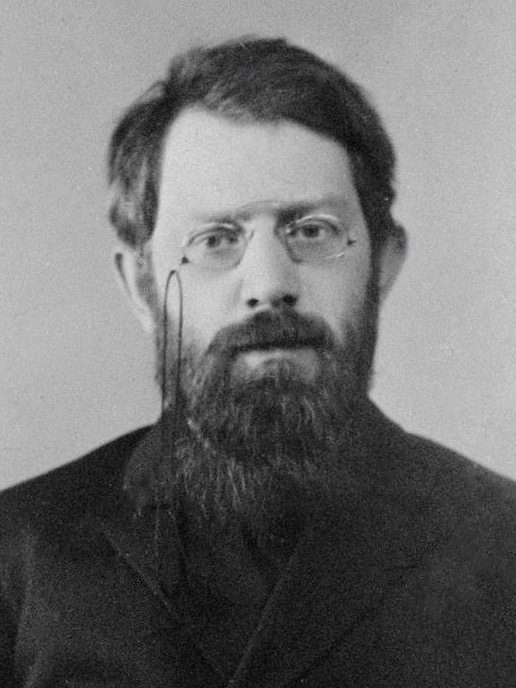

AND PETER STRUVE

Peter Struve

In 1911 the question of a Ukrainian national culture was raised in a controversy between Jabotinsky and Peter Struve. Struve was at the time one of the leading theorists of the Constitutional Democratic Party - the 'Cadets'. In an earlier phase of his life he had been, together with Lenin, one of the leading theorists, at the moment of its formation, of the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party. Struve's biographer, Richard Pipes, complains that 'The Ukraine was always Struve's blind spot.' But he explains Struve's position very clearly:

'Struve believed that a pervasive sense of national identity capable of overriding social, ethnic, and political divisiveness was essential to Russia's survival. He thought that the Russia of his time was not as yet a fully formed nation, but only a nation in statu nascendi: he once described it, using an American expression, as a "nation in the making." Like the United States, the Russian Empire consisted of diverse ethnic groups, and like it, he believed, it was being forged into a single nation by the unity of culture, in which Russian culture performed the same function as English culture did in America. The on-going process of cultural integration enabled him to argue that despite its ethnic heterogeneity Russia was not a multinational empire like Austria-Hungary with which it was often compared, but a genuine national state (or "national empire") like Great Britain and the United States. Given his views that Russia's national unity was determined not ethnically but culturally and that cultural amalgamation was still in progress, it is not surprising that he should have attached such importance to the maintenance of the unity of Russian culture: the latter was a precondition for Russia's political and moral recovery as well as for her future development as a great power. He regarded a single culture as even more important to Russia's future than unified statehood - hence, political separatism was to him less pernicious than cultural separatism. The Ukrainian national movement struck at the heart of this conception. To have conceded the existence of a Ukrainian culture alongside an all-Russian culture, or to have reduced all-Russian culture to its narrowly ethnic "Great Russian" manifestations, would have undermined the very premise on which his notion of the future of a great Russia rested: "If the question of the separation of the non-Russian nationalities has an exclusively political interest, then the Ukrainian movement, by contrast, confronts us with cultural separatism," a much more dangerous threat:

'"Should the intelligentsia's 'Ukrainian' idea . . . strike the national soil and set it on fire . . . [the result will be] a gigantic and unprecedented schism of the Russian nation, which, such is my deepest conviction, will result in veritable disaster for the state and for the people. All our 'borderland' problems will pale into mere bagatelles compared to such a prospect of bifurcation and … should the 'Belorussians' follow the 'Ukrainians' - 'trifurcation' of Russian culture."' (8)

(8) Richard Pipes: 'Peter Struve and Ukrainian Nationalism', Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 1979-1980, Vol. 3/4, Part 2, pp.675-6. The essay is actually an extract from Pipes's book Struve: Liberal on the Right, 1905-1944 which had not yet been published.

The controversy concerning Jabotinsky began, unsurprisingly, not with the Ukrainian question but with the Jewish question. In 1909, a Russian novelist, Evgenii Chirikov, had declared that Jews had little to contribute to Russian culture because they could not understand or enter into the experience of what it was to be Russian. Jewish writers protested, insisting on their own deep attachment to Russian culture. When Jabotinsky weighed in, however, he could hardly, as a Zionist and cultural separatist, be expected to defend Jewish identification with Russia. Instead, he launched an attack on the Russian liberal press, which had held aloof from the controversy, accusing them not of antisemitism but of 'asemitism', of effectively pretending that the Jews as a distinct people and therefore as a 'problem', didn't exist. Since the Jews and the Jewish problem did exist, this meant that the only people addressing it, apart from some Jews such as himself, were the antisemites.

According to the account by Olga Andriewsky (p.259):

'Jabotinsky's scathing indictment of the Russian intelligentsia, published as it was in Slovo [a leading liberal journal - PB], excited an immediate and passionate response in intellectual circles throughout the empire. In the words of Joseph Schechtman, Jabotinsky's biographer, fellow Zionist, and life-long friend, these four essays, with their penetrating analysis of Jewish interests, had an "almost revolutionary impact on Jewish intellectual circles." The reaction in Ukrainian circles was vivid as well. The leaders of the Society of Ukrainian Progressives (Tovarystvo ukrains'kykh postupovtsiv or TUP), who were themselves engaged in an ongoing struggle against the Russian intelligentsia's "conspiracy of silence," welcomed the Jewish publicist's frankness enthusiastically. Among other things, Jabotinsky's timely remarks underscored their own growing conviction that the Russian intelligentsia simply did not treat the nationalities problem seriously. As Rada, the leading Ukrainian-language daily, noted: "It can only be hoped that this polemic concerning the nationalities question that is currently being conducted with such emotion on the pages of the Russian progressive press will enlighten [Russians] about the true state of affairs and will help the progressive elements of all nations to reach an understanding more quickly so that [our] common forces can better fight for universal human ideals."'

Rada was, between 1906 and 1914, the only Ukrainian language daily paper. The Society of Ukrainian Progressives had been formed out of a series of shortlived clandestine Ukrainian political groups - the Brotherhood of Taras (formed in 1891), which gave way in 1897/8 to the General Ukrainian Non-Party Democratic Organisation which, in 1904, became the Ukrainian Democratic Party which, in 1905, fused with its own breakaway, the Ukrainian Radical Party to form the Ukrainian Radical Democratic Party. Also associated with the TUP (the Progressives) was the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, formed out of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party which was another derivative from the Non-Party Democratic Organisation. The Ukrainian Social Democratic Party included among its leadership Dmytro Dontsov who was to become a leading theorist of Ukrainian Fascism in Polish Galicia in the 1920s, together with Volodomyr Vynnychenko and Simon Petliura. Petliura in particular was part of the editorial secretariat of Rada and, together with Vynnychenko, of the elected council of the TUP. (9)

(9) This account was put together out of the relevant entries in the online Encyclopaedia of Ukraine.

STRUVE AND THE UKRAINIANS

Struve's confrontation with Ukrainian nationalism began in earnest in 1911. He seems to have accepted Jabotinsky's view that the national question needed to be addressed and to have invited him to contribute an article - The Jews and their attitude - to his own paper, Russkaia Mysl', in January 1911. But Jabotinsky's argument that the Great Russians were only a minority in a country made up of national minorities, and that the Jews knew very little about the Great Russians - their main experience was of Little Russians and Belorussians - prompted a speedy reply repudiating the term 'Great Russian' and insisting instead on the term 'All-Russian' - a single nation with regional variations.

Through 1911, as the debate was joined by a Ukrainian separatist writing anonymously, it turned on the question of language, Struve insisting that Russian, which had already established itself as a language of culture, had to be the 'koine', or common language, and that Ukrainian, in its different varieties, could never be anything other than a colourful regional patois. The case was developed in a major essay in 1912 on The Common Russian culture and Ukrainian particularism. Andriewsky suggests that the debate may have inspired Lenin, always attentive to whatever Struve might be doing, to write his own Theses on the National Question (1913). This was closely followed by Stalin's Marxism and the national question which endorses Ukrainian national autonomy, comparing the relationship between Ukraine and Russia with the relationship between Ireland and Britain:

'But the nations which had been pushed into the background and had now awakened to independent life, could no longer form themselves into independent national states; they encountered on their path the very powerful resistance of the ruling strata of the dominant nations, which had long ago assumed the control of the state. They were too late!...

'In this way the Czechs, Poles, etc., formed themselves into nations in Austria; the Croats, etc., in Hungary; the Letts, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, etc., in Russia. What had been an exception in Western Europe (Ireland) became the rule in the East.

'In the West, Ireland responded to its exceptional position by a national movement. In the East, the awakened nations were bound to respond in the same fashion.

'Thus arose the circumstances which impelled the young nations of Eastern Europe on to the path of struggle …

'The only correct solution is regional autonomy, autonomy for such crystallised units as Poland, Lithuania, the Ukraine, the Caucasus, etc.'

The national question became urgent with the outbreak of war with Austria and Germany, especially once Russia invaded Austria, and Eastern Galicia came under its control. On 1st August 1914, the three main political parties in Galicia - the National Democratic Party, the Ukrainian Radical Party and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party - formed a 'Supreme Ukrainian Council' which organised the 'Ukrainian Sich Riflemen' as a unit in the Austrian army. They were joined by the 'Union for the Liberation of Ukraine', representing Ukrainians under Russian domination, mostly Socialists. The Union (SVU, from its name in Ukrainian) was led by, among others, Dmytro Dontsov. Though originally centred in Lviv it moved, together with the Supreme Council, to Vienna (where the Supreme Council became the 'General Ukrainian Council') According to the account in the Encyclopaedia of Ukraine:

'As a result of its efforts about 50,000 prisoners of war in Germany and 30,000 in Austria were provided with hospitals, schools, libraries, reading rooms, choirs, orchestras, theaters, and courses in political economics, co-operative management, Ukrainian history and literature, and German language. Various newspapers were established, including Rozsvit (printed in Rastatt), Vil’ne slovo (Salzwedel), Hromads’ka dumka (Wetzlar), Rozvaha (Freistadt), and Nash holos (Josefstadt). A number of educational brochures were also published.'

The POW camps thus provided the Ukrainian nationalist intelligentsia with the opportunity that had always been denied them in Russia to make contact with the Ukrainian-speaking populace.

Struve was alarmed by a speech given by a Ukrainian deputy in the Austrian Parliament 'calling for the creation of a Ukrainian buffer state that could isolate "Muscovite Russia" from the Black Sea.' (Pipes, p.679). He launched into a ferocious polemic against the liberals, including members of his own Cadet Party, who were prepared to acknowledge Ukrainian claims to a separate culture - the disagreement with his fellow Cadets eventually resulted in his resignation from the Cadet Party's Central Committee. In December 1914 he travelled to newly occupied Galicia and on his return argued that the so-called Ukrainian culture in Galicia, like the Greek Catholic Church, was 'nothing more than a "surrogate culture", originally created by the Orthodox population of the area as a weapon against Polish domination … A deep and broad Russification of Galicia is necessary and unavoidable."' (Pipes, p.681).

The Russian administration seems to have agreed, especially after the first occupation governor, the Polonophile Sergei Sheremet'ev was replaced by Georgii Bobrinskii, a relative of the Galician Russophile leader Count Vladimir Bobrinskii. Street and place names were changed, the Shevchenko Scientific Society was closed down, the popular Metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church, Andrei Sheptyts'kyi, was arrested and deported. Ukrainian writers associated with the journal Dnister, and the newspaper Dilo were arrested:

'In general the Ukrainian movement was crushed: the press was suspended, the Ukrainian national colours were banned, copies of Taras Shevchenko's "incendiary" collection of poems, Kobzar, were confiscated, and several hundred members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia were arrested.' (10)

(10) Mark von Hagen: 'Wartime Occupation and Peacetime Alien Rule: "Notes and Materials" toward a(n) (Anti-) (Post-) Colonial History of Ukraine', Harvard Ukrainian Studies , 2015-2016, Vol. 34, No. 1/4, p.158.