THE AESTHETIC OF BEURON

There is much that could be said about Denis but I want to jump straight on to my own personal reasons for finding him interesting.

In 1942, shortly before his death, Denis published a life of his friend and colleague, the painter Paul Sérusier. (16) In it, he describes how, shortly before Gauguin left for Tahiti in August 1891 he 'placed in his [Sérusier's] care a pupil who would occupy a key place both in Sérusier's affections and in his destiny. It was the young Dutchman, Jan Verkade ...' (p.60) (17)

(16) Paul Sérusier: ABC de la Peinture, suivi d'une étude sur la vie et l'oeuvre de Paul Sérusier par Maurice Denis, Librairie Floury, Paris, 1942.

(17) Though according to Verkade's own account, which Denis also quotes, he went straight to Sérusier without passing by Gauguin.

While he was with Sérusier in Brittany, Verkade, from a Dutch Mennonite background, converted to Catholicism and in 1893 he became a monk, joining the Benedictine monastery of Beuron in Germany and taking the name Willibrord.

Jan Verkade: Self portrait as monk, nd.

Beuron was the centre of an extraordinary experiment in painting, conducted under the guidance of the sculptor and painter, Peter, in religion Father Desiderius, or Didier, Lenz.

Maurice Denis: Fr Desiderius with young monks, 1904

Lenz believed that he had found in old Egyptian and classical Greek art various mathematical formulae that underpinned the harmony of the world and therefore also the harmony of the work of art. Beauty in art would be achieved not by copying a beautiful model but by organising the work on the basis of these mathematical principles. Denis had said that before anything else a painting was a flat surface covered in colours assembled in a certain order. But neither then nor subsequently did he have anything much to say about what that 'certain order' might be. Lenz seemed to be offering a clear idea. Instead of the flat surface covered in colours bending to the needs of the subject being represented, the subject being represented would have to conform to certain abstract principles dictated by the nature of the flat surface. It was a principle well suited to the development of a hieratic art, and indeed we might remember the phrase I quoted earlier from Trubetskoi: 'in the icons, human figures are, so to speak, sacrificed in favour of the lines of the architecture.'

Lenz: study for the canon of the human body, nd

(Krins: Die Kunst der Beuronschule, p.47)

Trubetskoi's thought is in my view the most important and intelligent reflection on the icon that I know so perhaps I should take this opportunity to quote him further:

'This subordination to the architectural order can be seen not only in the temple as a whole but in each painted image, considered separately. Each icon has its own internal architecture which remains visible, even independently of any immediate relation to the structure of the temple ...

'It is the architectural character that, more than anything else, marks the difference between the old iconography and realistic painting. We see the human form adapting to the lines of a church - here it is too rectilinear, there abnormally curved to harmonise with the curve of a vault ...

'The architectural character of the icon expresses one of its central and essential ideas. Iconography is a "catholic" painting. The predominance of architectural lines over the human figure expresses the subordination of man to the idea of "catholicity" [sobornost], the primacy of the universal over the individual. Man ceases to be a self sufficient person to enter into the overall architecture of the whole.' (pp.31-3)

Virgin of Jerusalem, mid XVIe century, Vologda

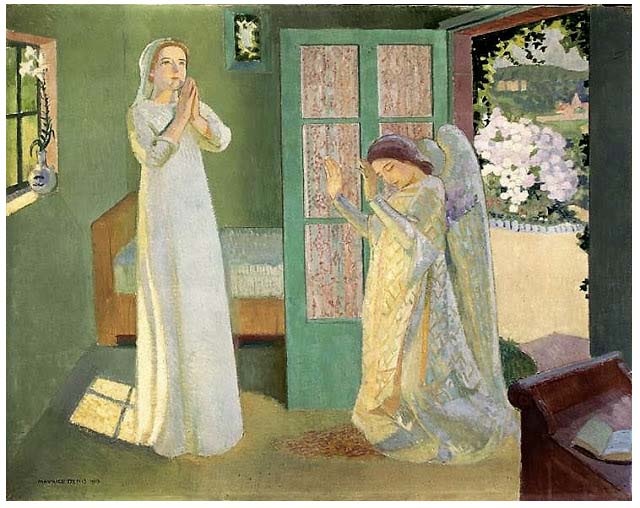

In 1896 Denis published an essay Notes on religious painting,(18) dedicated to Verkade. In it, he defined 'two kinds of religious painting':

"The one is sentimental, if I dare say so, restoring the beauty of the attitudes of prayer, of heads inclined in ecstasy, of kneeling; purity, naivety of veiled young girls, the nine hours in the morning of a first communion. It is the feminine manifestation of Catholicism, the art of fashioning scenes with the memory of pious feelings, of showing the Saints, the Spirits, wrapped in such feelings; to picture God in the image of our sorrows, of our melancholy, of our desires.

Maurice Denis: Annunciation, 1913

'The other is less inspired by life and, in order to realise the absolute, turns to the intimate secret of nature - to number. From the mathematical relations of lines and colors there appears a supernatural Beauty which is only slightly troubled by a hint of human suffering which runs through it, as if to add a discreet accent of life and of prayer to the expression of divine harmony. That is the prestige of the perfect chord, the splendour of immutability. Instead of evoking before the object that is being represented emotions we have experienced in the past, it is the work itself which wishes to move us. This unshakeable spiritual beauty is complemented by the beauty that surrounds it; the admirable harmonies are a representation of the truth from on high; proportions express concepts; there is an equivalence between the harmony of the figures and the logic of Dogma.

Think of the Egyptians, of the Byzantine mosaics in Italy, of Cimabue.'

Altarpiece of St Gabriel's Church, Prague, done under the supervision of Fr Desiderius.

(18) L'Art et la Vie, a journal edited by the future Action Française activist, Maurice Pujo, octobre 1896. Théories (1922 ed), p.30.

The following year, 1897, Sérusier visited Verkade in Prague - the Benedictines had been banished from their monastery as part of Bismarck's 'kulturkampf', his political struggle with the Catholic church. The experience was overwhelming. On his return he wrote to Verkade saying:

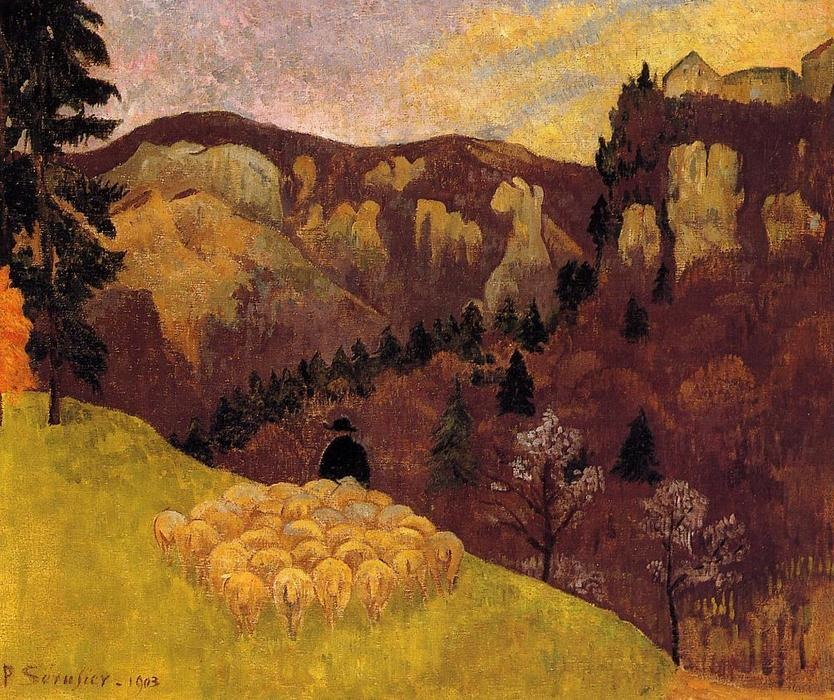

"Yes, you are right. Art must be hieratic. It is not without regret that I say goodbye to the landscapes, the cows, the Bretons who charm and amuse the eye, but I know that I have to apply myself to an art that will be grander, more severe and sacred ... I have come back to the sacred measures ... and I admit that it isn't easy and I'm getting a bit lost in it all.' (Denis' Vie de Sérusier, p.76)

As Denis observes 'Thank God, Sérusier won't, as he claimed, abandon nature, nor the Bretons':

Paul Sérusier: The flock in the Black Forest, 1903.

Beuron is situated in the Black Forest so this lovely but rather un-Beuron-like painting may have been painted during a visit to the monastery

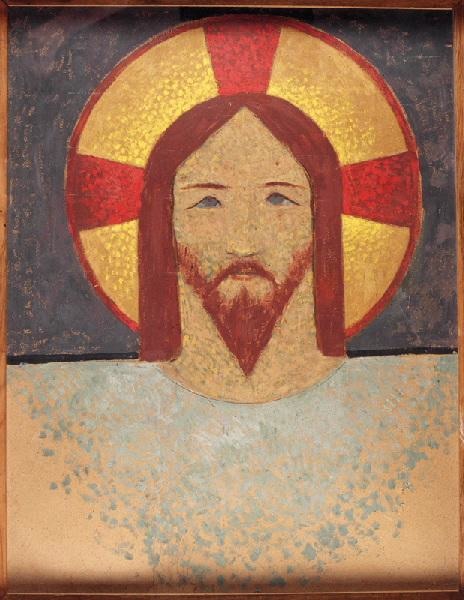

As it happens his more obviously mathematically calculated works are not very convincing:

The Holy Face, nd

In 1905 he published a French translation of a theoretical statement by Lenz under the title L'esthétique de Beuron, largely a statement of the historical background and intentions of the school rather than a practical guide. (19)

(19) An English translation is available: Desiderius (Peter) Lenz: The Aesthetic of Beuron and other writings, translated by John Minihane (sic. should be Minahane) and John Connolly, Introduction and appendix by Hubert Krins, Afterword and notes by Peter Brooke, Francis Boutle publishers, London, 2002. The other, later, texts do give more detail as to the practical methods proposed. See also Hubert Krins: Die Kunst der Beuroner Schule - Wie ein Lichtblick vom Himmel, Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron, 1998

It was published by the journal L'Occident. Denis was art critic of L'Occident and contributed a preface to the book. At this time the Beuron monks were working on their most important commission, decorating St Benedict's own monastery at Monte Cassino. Denis visited them in Monte Cassino in 1906. Their work was destroyed by allied artillery fire in 1944 but recently, very happily, the crypt has been restored:

There is an amusing letter of Sérusier's from 1908 when he visited Verkade in Munich:

'München 16 January 1908

Bei Frau Dormaul 15 Giselastr Parterre

'On my arrival I found Father Willibrord in rather a bad way. Happy as a bird that has escaped from his cage, he has been delighting in forbidden fruit, he has been making very nondescript academic studies and still lifes which are inferior to those he did when he arrived in Paris. He was complaining that Father Didier had frozen his sensibility and that he wanted to warm it up again with the curves of a young woman from Munich. He has been commissioned at Beuron to do a Virgin flanked by two angels offering flowers. Working from nature he had made his angels into street flower sellers with bellies and hips that were very un-seraph-like.

'Happily, at Christmas he went to Beuron bringing his project with him to see it on site. That is where I went on the 1st January. The experiment was decisive. He saw that everything that Fr Didier has found is necessary to a religious, monumental art. Since then, he has dismissed his model and taken out his compasses. I am very pleased about it.' (ibid., p.92)

Verkade did much travelling, promoting the Beuron idea. While in Munich, he shared a studio with the Expressionist painter, later involved with Kandinsky and Klee in the Blaue Reiter, Alexei von Jawlensky. One can see how Verkade could have been tempted ...

Alexei von Jawlensky: Landscape near Murnau, c1907

Now you may feel cheated in an article supposedly concerned with Denis' influence on Sister Joanna, when I tell you that although Denis was indeed involved with the Beuron project through his friendship with Verkade and Sérusier, he himself never adopted it and in fact was quite hostile to it, especially once the war broke out in 1914 and he became very hostile to all things German. His correspondence with Verkade comes to an end in 1913. In an essay published in 1916 (20) and included as the first essay in Nouvelles Théories (1922) Denis aims to settle accounts with the German influence on French art and culture:

'Mr Charles Morice in the Mercure de France has freed himself from all German influence, except perhaps that of Novalis, literary symbolism. Neither Gauguin nor Cézanne took anything from the art across the Rhine. In Impressionism and the more recent schools we find a bit of everything: Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites. the Japanese. Breton calvaries, the images of Épinal, Italian primitives, oceanic idols, but nothing Germanic; and if our sympathetic curiosity once led us towards the Benedictines of Beuron it must be said that we got nothing from it other than some very general insights on sacred art.' (p.26)

(20) Maurice Denis: 'Le Présent et l'avenir de la peinture française', Le Correspondent, 25 November 1916. Republished in Denis: Nouvelles Théories, L.Rouart & j.Watelin, Paris, 1922.

My justification for evoking the connection with Beuron is to point to a Catholic/Encounter that might have taken place through Denis and which I think might have been interesting since what Beuron was proposing was indeed, as Sérusier says, a hieratic art. The Orthodox icon is, necessarily, a hieratic art simply because, unlike a fresco which illustrates an event in sacred history, it is an object of veneration. In a talk he gave on the current state of religious art (21), Denis drew this distinction between religious art and art of veneration but, as a Catholic, he saw it as a distinction between painting (religious art) and sculpture (object of veneration). Complaining about the poor quality of contemporary church sculpture, he says:

'We await impatiently a work of religious sculpture which would be as remarkable in plastic originality as it is in the feeling expressed: up until now we have seen nothing in modern art, that would be the equivalent of, for example, a painting by Desvallières. I would go so far as to say that it is of work of this kind that we have the most need; a church can do without paintings, but not without statues. The piety of the faithful demands one for every object of devotion. It is certainly a disheartening problem for an artist to create a model that will be mass-produced, enlarged, shrunken, painted garishly, for use anywhere. It is quite another matter to translate into an original style attitudes, drapery, and expressions already fixed by tight conventions, to renew them without shocking the habits of the faithful, more demanding here than they are in matters of painting. To renew subjects such as Our Lady of Lourdes, Saint Anthony of Padua, the Sacred Heart, we lack a man of genius.' (pp.275-6)

(21) Maurice Denis: 'Dernier état de l'Art chrétien et l'École d'Art sacré', Nouvelles Théories, p.259.

That expresses quite well at least part of the problem of the icon. Because it is an object of veneration the artist is constrained. He has to produce something the people are willing to venerate. And it has to be something other than a reproduction of a lovely form. It has to be 'hieratic'. It may be relevant here to say something about the views of Fr Sergei Bulgakov, Sister Joanna's spiritual father (her first spiritual father, prior to, at the end of her life, Alexander Men).