JEWISH EMIGRATION

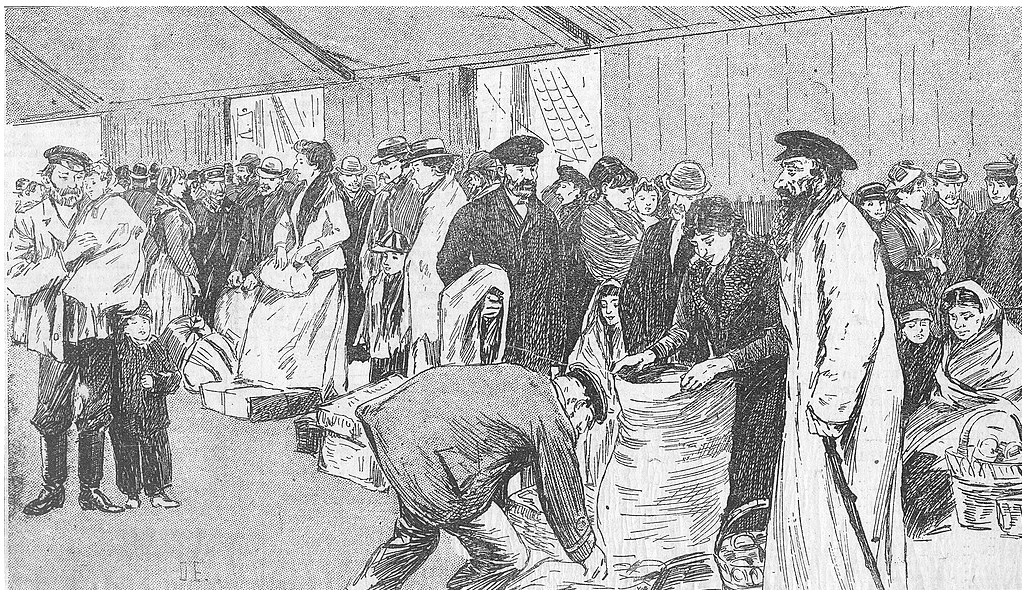

Jews arriving at Tilbury Port, London, 1891

Frankel is primarily interested in the intellectual history of the radical - Socialist and Zionist - Jewish movements of the time. Something should be said about the social circumstances in which these ideas were being developed.

Perhaps the most obvious symptom of the Jewish problem was the steady increase in emigration, overwhelmingly to the United States. Frankel gives as figures 37,011 in 1900, 77,544 in 1904. 92,388 in 1905, and 125,234 in 1906. Solzhenitsyn argues (p.326) (10) that 'Jewish emigration to America remained weak until 1886-7. It saw a brief rise in 1891-2, but it was only after 1897 that it became massive and continuous.' He argues that what made the difference was the legislation introduced in 1896 imposing a state monopoly on the production and sale of alcohol.

(10) Alexandre Soljénitsyne: Deux siècles ensemble, t.1, Juifs et Russes avant la révolution, Eds Fayard, 2002. English translations are my own from the French. Nearly twenty years after the French edition it hasn't yet been officially translated into English, though some unofficially translated extracts can be found on the internet.

According to the Pahlen Commission (1886), 'Jews owned 27% (rounded figures) of all the distilleries in European Russia, 53% in the Pale of Settlment (notably 83% in the province of Podolsk, 76% in that of Grodno, 72% in that of Kherson). They held 41% of the breweries (11) in European Russia, 71% in the Pale of Settlement (94% in the province of Minsk, 91% in that of Vilnius, 85% in the province of Grodno). As for the share of commerce in alcohol held by the Jews, the proportion of the places of fabrication and sale is 29% in European Russia, 61% in the Pale of Settlement (95% in the province of Grodno, 93% in that of Moghilev, 91% in the province of Minsk).' (p.325.)

(11) Brasseries in the French which could mean either brewery or small café serving alcohol.

The law taking state control of the production and sale of alcohol therefore hit hard at one of the major areas of economic activity that were available to poorer Jews. It didn't prevent Jewish domination of the sugar industry, the timber industry, the export of grain, railways and navigation, military supplies, the oil industry round Baku and of course the financial services industry. Zhitlovsky came from a wealthy timber processing background and Frankel quotes him saying:

'Samuil Solomonovich Poliakov builds railways in Russia. These railways, according to Nekrasov's famous poem which reflects the true socio-economic fact, are built on the skeleton of the Russian peasantry. My uncle, Mikhail, brews spirits in his distillery for the Russian people ... My niece, Liza, sells the spirits to the peasant. The whole shtetl lives from the Russian peasant. My father (in Vitebsk) employs him to cut down Russian woods which he buys from the greatest exploiter of the Russian muzhik - the Russian noble ... Wherever my eyes rested I saw only one thing ... the harmful effect of the Jewish tradesmen on the Russian peasantry' (p.263. Unfortunately Frankel's reference doesn't give a date).

A major Jewish grievance was their confinement in the Pale of Settlement. Nonetheless Solzhenitsyn says (p.315) that according to the 1897 census there were 315,000 Jews living outside the Pale, about 9% of the Jewish population in the Empire (excluding the Kingdom of Poland) and nine times what the figure had been in 1881. Solzhenitsyn contrasts this with the figures of 115,000 Jews in France and 200,000 in Great Britain. Nonetheless their position was fragile as witnessed in 1891 when the Grand Duke Sergius (assassinated in 1905) expelled some 20,000 Jewish artisans from Moscow in the middle of the winter. A further 70,000 (families whose presence outside the Pale was technically illegal but who had previously been officially granted a toleration) were expelled in 1893.

Solzhenitsyn (p.343) claims that, despite English protests against Russian government policy, 'after evaluating the proportions that the flood of emigration risked taking, Great Britain soon brutally closed its doors.' He is referring to the Aliens Act, introduced in the last days of the Unionist government (the government of Joseph Chamberlain who offered east Kenya to Herzl and Arthur Balfour of the Balfour declaration) in 1905. This was at least partly a response to antisemitic riots in South Wales in 1902 and 1903 and to demonstrations by the 'British Brothers League', formed in 1901 to protest against immigration and claiming some 45,000 members (probably meaning, according to Wikipedia, signatures to its manifesto).

Nevertheless, Solzhenitsyn is exaggerating. According to an account by an academic historian, Jill Pellew of the University of London:

'The 1905 Act specified that at certain "immigration ports" where immigrant ships would be allowed to discharge passengers, there were to be immigration officers (supported by medical officers) with power to reject those who came within special categories of "undesirable". An "undesirable" immigrant was specified in the act as someone who could not show that he was capable of "decently" supporting himself and his dependants, although a special clause (added through the efforts of [Sir Charles] Dilke and company) made an exception for immigrants who were seeking entry as political or religious refugees ... The term "immigrant" was defined as an "alien steerage passenger" although not one who had a pre-paid onward ticket. As far as "undesirables" already in the country were concerned, the secretary of state could deport certain convicted alien criminals if the sentencing court recommended expulsion, and also aliens who, within twelve months of landing, were found in receipt of parochial relief.' (12)

(12) Jill Pellew: 'The Home Office and the Aliens Act, 1905', The Historical Journal, Vol 32, No 2, June 1989, p.373.

But the act was left to be implemented by the new Liberal government, and specifically by the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone and his Parliamentary under secretary, Herbert Samuel, himself a Jew (and later first High Commissioner for Palestine). Pellew goes through their handling of it in some detail. Immigrants were judged to be unable to support themselves if they had less than £5.00 in their pockets. Friends and sympathisers arranged for them to have the £5.00, sometimes passed from passenger to passenger. Initially boats with less than twelve steerage passengers were exempted. That became less than twenty and frequently immigrants found themselves waiting until a boat with less than twenty steerage passengers became available. Pellew concludes: 'The fact was that Gladstone and his party, even though they had come into power with a landslide victory at the end of 1905, did not wish to go through the trauma of bringing the unappetising Aliens Act up again in parliament by proposing its repeal. Gladstone was under parliamentary pressure to relax the regulations, particularly in the early days, Samuel was looked on as an ally of his fellow Jews. Therefore the compromise which they reached between administering the law as its legislators intended and repealing it altogether was to administer it badly.' (pp.378-9)

Returning to the situation in the Russian Empire another of the motives Solzhenitsyn gives for Jewish emigration was the desire to avoid conscription, which would help to account for the increase in 1904, the year of the Russo-Japanese war. This brings us to 1905, the year of the Revolution, the formation of the Constitutional Democratic Party (the 'Cadets') which became the main political vehicle arguing for Jewish rights, the Union for Equality of Rights in which Vladimir Jabotinsky began to make his mark, the role of Parvus and Trotsky in the formation of the St Petersburg soviet, a series of pogroms which marked an exponential increase in the number of Jewish deaths (47 in Kishinev in 1903, 800 in Odessa in 1905, according to Frankel) not to mention the subsequent formation of the SERP - Jewish Socialist Labour Party - and ESDRP(PZ) - Jewish Social Democratic and Labour Party (Poale Zion), the return of the Bund to the RSDRP, the second, much more politically determined aliyah to Palestine, and the highly publicised Beyliss ritual murder trial. I had hoped to be able to finish the series with this article, bringing the story to the end of the period covered in Solzhenitsyn's first volume, but so much remains to be said that at least one other article will be necessary.