THE 'BUND' AND RUSSIAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY

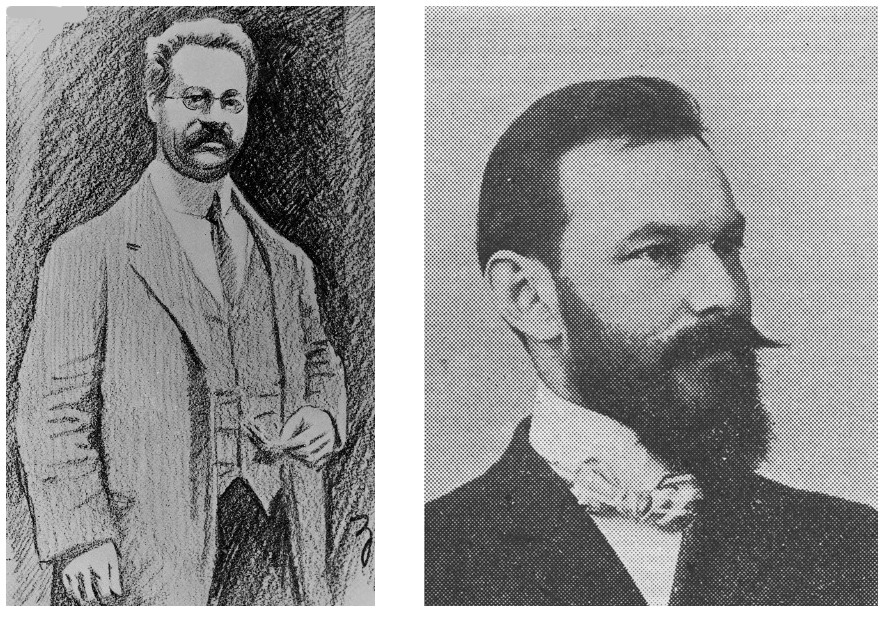

Aleksandr 'Arkadii' Kremer John Mill

Just as the first 'aliyah' ("ascent" - emigration to Palestine) followed the pogroms of 1881-2, so the second aliyah followed the pogroms of 1903 and 1905-6. But much had happened in the interim, most notably the development of a more militant and self consciously Jewish politics, together with the influence of Marxism and the appearance, with the First Zionist conference, held in 1897, of trans-national Zionism.

1897 also saw the formal establishment in Vilnius (Lithuania) of the Jewish Marxist organisation, the 'Bund' - the General Jewish Labour Union in Lithuania, Poland and Russia - six months before the formation of the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party (RSDRP - Rossiiskaia Sotsial-Demokraticheskaia Rabochaia Partiia). The RSDRP's first congress was held in Minsk in March 1898 with eight delegates, five of whom were Jewish, including three members of the Bund, two of whom joined the initial three member central committee. The main weight of what the RSDRP was soon to become was still in exile, mainly in Switzerland.

Jonathan Frankel, whose book Prophecy and Politics (1) will be the main source for this article, says that the early history of Socialist Zionism in the Russian Empire has not yet been sorted out but he believes that the first use of the term 'Poale Zion' (workers of Zion) was in Minsk, also in 1897. It may be noted that Minsk and Vilnius and in general the areas where these political developments were taking place, were far removed from the South East of the Pale of Settlement, Ukraine, where most of the pogroms occurred.

(1) Joseph Frankel: Prophecy and Politics - Socialism, Nationalism and the Russian Jews, 1862-1917, Cambridge University Press, 1984 (first published 1981)

The Bund originated in a Marxist self education group in Vilnius in the 1880s. One of the leading figures at that time was Lev Yogikhes, who went on to join Rosa Luxemburg in the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland (later, 1899, Poland and Lithuania) founded in 1893/4 (2) in opposition to Pilsudki's Polish Socialist Party (PPS) with its emphasis on Polish national separatism. In the 1880s, the Jewish group was being encouraged to move into an international culture - Marx and Darwin - by means of the Russian language, in other words to cease being distinctively Jewish. This changed with the arrival from prison early in 1890 of Aleksandr Kremer ('Arkadii'). He and his colleague Shmuel Gozhansky, began to push for an emphasis on agitation specifically directed at the Jewish community, using Yiddish as the language. In Frankel's account this was opposed by the working class membership who saw themselves being sent back into a milieu they thought they were escaping:

'Previously, the movement had acted as a way of escape for the worker from the old environment into a completely new world with a new language (Russian), a new culture (Russian libraries), a new faith (socialism), a new peer group (the intelligentsia) and ever widening horizons (the international socialist movement). But, as now envisaged, the movement was to become that of the Jewish working class with Yiddish as the language, the local workshop as the focal point, and "trade unionism" or kassy and economic strikes - as the major form of activity.' (p.180)

(2) Frankel gives both years on the same page. The confusion may be due to the difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars. In my use of dates - as with my transliteration of Russian or Hebrew names - I have in general just followed my sources without researching the matter myself. The 'Kingdom of Poland' was the area of Poland that had come under Russian suzerainty in the wake of the Napoleonic wars (ie not as a result of the repartitions in the eighteenth century) with its capital in Warsaw. Pilsudski's party, with its nationalist ambitions, was organised across the whole territory of what was deemed to be historic Poland.

The new tendency was also opposed by Luxemburg and Yogikhes, who saw it as potentially a Jewish equivalent of Pilsudski's national identity oriented PPS. But it was supported in an influential speech delivered in Vilnius in 1895 by 'Martov' (Julius Osipovich Tsederbaum), later leading theorist of the Mensheviks and, as we shall see, opponent of the Bund.

One of the problems for Jews inspired by Marxism was that there wasn't a large scale Jewish proletariat. Jewish workers were typically artisans working in small scale workshops. Kremer argued that, paradoxically, this could be seen as an advantage. Quoting Frankel (pp188-9), 'An artisan employed in a workshop did not fear dismissal as much as a factory hand because there were innumerable other small shops where he could find work, and this was doubly true if he was skilled. If the worst came to the worst he could even set up on his own. Further, as a class these skilled workers were better educated than the factory proletariat and were more easily organised ... True, he admitted, domestic and handicraft production was doomed and would ultimately be replaced by large scale industry. But this fact made it doubly important that the workers in small-scale production face the harsh transitional period as a united entity. Otherwise they would be exposed to limitless exploitation and degradation. The goal should be to provide the worker with the means of defence whether he remained where he was or moved to a new industrial setting. "We are lucky,' he concluded, "that we live in an epoch where the process of change is so clear that we can foresee all the subsequent stages. To know that process and not to use that knowledge would be to commit a major historical error."'

Kremer and Gozhansky also argued for a distinct Jewish organisation on the grounds that Russian democracy couldn't be trusted to defend Jewish rights. Referring to Gozhansky's Letter to the Agitators which, he says, was probably written late in 1893, Frankel says (p.189):

'There could be no doubt, he wrote, that in the foreseeable future the Russian Autocracy would fall and be replaced by a constitutional system, but it was no longer possible to assume that a more democratic regime would automatically bring with it political equality for the Jews. Recent history clearly demonstrated that even parliamentary systems could deprive minorities of their rights, either through legislation (as in Roumania) or through intimidation and privilege (as in Austria-Hungary). Indeed "in constitutional Roumania, the Jews have fewer rights than in autocratic Russia.'

The position was summed up by another supporter of the new line, John Mill, (3) declaring:

'that the Jewish workers suffers in Russian not merely as a worker but as a Jew; that in agitation all forms of national oppression should be stressed more and more; that, together with the general political and economic struggle, the struggle for civil equality may be one of our immediate tasks; and that this struggle can best be carried out by the organised Jewish worker himself.' (Frankel, p.190).

(3) Mill's Jewish name was Yoyself Shloyme Mil. It may be a reasonable speculation that he adopted the name 'John' rather than his own 'Joseph' or the Russian 'Ivan' in homage to J.S.Mill, much admired in Russian liberal and nihilist circles.

Bund domination of the RSDRP didn't last long. Already in late spring 1897, before the formal establishment of either the Bund (September 1897) or the RSDRP (March 1898), Kremer had had what Frankel calls a 'disastrous' encounter with Plekhanov (Plekhanov accompanied by Akselrod and Vera Zasulich). The disagreement seems to have been that whereas Kremer argued for a sharp worker/capitalist division, Plekhanov was arguing for a temporary alliance with bourgeois liberalism in opposition to autocracy. Perhaps as a result of this confrontation Kremer seems to have decided that a definite Jewish structure (the Bund) needed to be established prior to the expected formation of a Social Democratic Party in Russia (a Russian Social Democratic Party Abroad existed already) if the Jewish voice was to be heard.

Kremer was arrested in 1898 and in his absence the Bund in 'Russia' became more internationalist, less concerned with Jewish autonomy, but in Berne, the Bund leadership in exile was developing in the opposite direction, arguing for a Jewish national autonomy - a right of the Jews within the Russian Empire to decide democratically their own affairs without, however, demanding a distinct territory of their own. The case was put by Mill in an edition of the paper Der yidisher arbeter published in 1899:

'No less a person than Karl Kautsky, Mill noted, had recently argued in the name of Marxist principles that to divide the Austro-Hungarian Empire into independent national states would solve nothing, for the problem of oppressed minorities would live on in the new states. Indeed, Kautsky suggested, the fate of the Jews and the Ruthenians in an independent Galicia would not be an enviable one. The optimal solution, therefore, was a reorganisation of the Hapsburg Empire which would grant each national group autonomy.' (Frankel, p.218)

Lenin, when he met Plekhanov in Switzerland, found him fiercely opposed to the Bund - indeed, according to Lenin's account, to the Jews in general:

'He declared straight out that this is not a Social Democratic organisation but simply an organisation of exploitation - to exploit the Russians. He felt that our goal is to kick the Bund out of the Party, that the Jews are all chauvinists and nationalists, that a Russian party must be Russian and not "give itself into captivity to the tribe of Gad," etc. ... G.V. was not to be moved from this position. He says that we simply have no knowledge of the Jews, no experience of conducting affairs with them.' (p.229)

In June 1903, in preparation for the second congress of the RSDRP to be held in Brussels in July, the Bund held its Fifth Congress in Zurich. This was in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom and feelings were running high. In Frankel's account (pp.240-241): 'Because the congress was held abroad, the nationalist wing enjoyed a much stronger position than in 1898 or 1901; it was numerically much larger and it had a chance to hammer out its position at a preliminary conference held in Geneva. Its leading spokesmen at the congress (Liber, Medem, Kossovosy and Zhenia Hurvich) demanded that the Bund finally develop a totally coherent ideology - unequivocally for national autonomy, for national as well as class agitation, for the right of the Bund to represent and work among the Jewish proletariat throughout the Empire.' A maximal demand was formulated which would have established a federal structure for the RSDRP but there was also a minimalist programme 'beyond which there was to be no retreat':

'Of the ultimata, the central one was the demand for recognition that "the Bund is the Social Democratic organisation of the Jewish proletariat, enters the RSDRP as its sole representative, and is not subject to any geographical restriction."'

In the event, though, when they arrived in Brussels they found to their surprise that their position within the RSDRP was the very first item on the agenda and they were subject to withering attack by almost all the other delegates led by the 'Iskrovtsy', associated with the party journal Iskra founded by Lenin and Martov (and printed as it happens on a clandestine printing press in Kishinev, conveniently placed as it was near the Roumanian border). As the conference proceeded. however, other divisions emerged, notably, among the Iskrovtsy themselves, the division that was to separate Bolsheviks and Mensheviks - the division between the advocates of a small, tightly knit body of professional revolutionaries (Lenin) and those who wanted a mass party (Martov). In these quarrels the Bund representatives generally supported Martov. The Bund's own resolution defining themselves as the 'sole representative of the Jewish proletariat' unlimited by geographical bounds was not voted on until weeks later, after the congress had moved to London. It was defeated by forty one votes to five (with five abstentions), whereupon the Bund representatives walked out, depriving Martov of their support and giving Lenin's supporters the majority that gave them the title 'Bolsheviks'.