HEIDEGGER

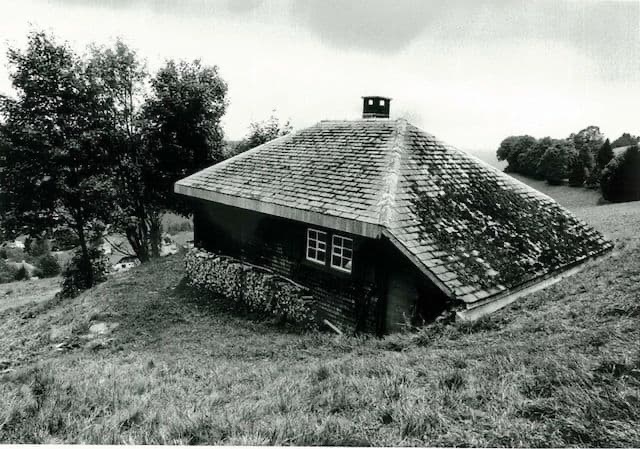

The hut near the Black Forest where Heidegger did much of his thinking

It may seem odd to bring Heidegger into a discussion of the 'multipolar world' but I have a particular interest in the interaction of politics and religion and it is as a 'religious' thinker - albeit not working in the limits of any particular denominational framework - that Heidegger interests me. The different 'poles' of a multipolar world are, we suppose, civilisational, and civilisations are often, indeed usually, formed on the basis of religion. Heidegger has exercised a fascination that crosses religious boundaries. Among the translators of Being and Time into English are an Anglican clergyman (John McQuarrie) and Joan Stambaugh, who has a particular interest in Buddhism. In this article I want to discuss aspects of Heidegger's influence in Iran and in Russia but I'll begin with a necessarily superficial overview of those parts of Heidegger's thinking that may be relevant to the subject.

Heidegger argues that the whole trajectory of the intellectual life of the 'West' (Europe, with its extension in America, North and South) was determined by the debates that took place in Greece over the meaning of the word 'being'. The human being is, in Heidegger's view, 'the unrecognised guardian of the truth of being' (3) - the only being capable of posing being as something to be thought about. Consequently there is a sense in which (my formulation not perhaps Heidegger's) 'being' is whatever we think it is. The quality of our own being and of our relation to the beings around us is determined by our conception of what being is, hence the importance of philosophy whose business it is to address the question of being. Though in Heidegger's view this isn't a matter of freedom to think whatever the philosophers like. What we think being is is dictated in some sense by 'the history of being' - the state that the concept of being has reached at any particular moment in history. The philosophers - at least the handful of philosophers Heidegger regards as important, don't say what they want to say but what they have to say, what being itself tells them to say.

(3) eg Martin Heidegger: Mindfulness, p.20 (in the Kindle version).

The Greeks, beginning in the reflections of the so-called 'pre-socratics' - Parmenides, Heraclitus, Anaximander - conceived of being in terms of 'metaphysics', meaning some 'thing' analogous to physics, to φυσις. Plato's 'ideas' are an obvious and highly influential example. Metaphysics has continued to underpin Western philosophy through to the nineteenth century when it reached its 'completion' in Nietzsche for whom being, reduced to nothing but the lowest common denominator of beings (the mere fact that they are beings), is replaced by power as the essential reality to which all beings have to bend.

Nietzsche's 'will to power' was not just a matter of political or military power. It was also manifested, most typically, in technology, in our ability to manipulate the world about us, to bend it to our own - usually rather frivolous - ends. Heidegger called this 'machination' (die Machenschaft). I've talked about bending the world to our own ends but in Heidegger's view it was more that machination was bending us to its ends. We follow, and we have to follow, its own logic. The present discussion of Artificial Intelligence might serve as an example. Once we know we can do this we have to do it - we have no choice. Heidegger called this the 'devastation' and saw it spreading from us - the civilisation that was initiated by 'the Greeks' - through the entire world, leaving no space for, say, poetry, or for a real encounter with the divine. Heidegger, whose initial training was as a theologian in scholastic philosophy, doesn't talk about 'God' but he does talk about 'the God', 'the last God', or 'the gods'.

He attached huge importance to the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin (youthful friend and companion of the philosophers Schelling and Hegel) whom he regarded as the man who, more than anyone else prior to himself, had the sense of what he called 'inceptual thinking' - the way in which the Greeks had seen the problem of being right at the beginning of Western philosophy. (4) Heidegger took the view that the thinking of the Greeks has now become impenetrable to us because we do not understand the words they used (partly as a result of their translation into Latin) but that with the 'completion of metaphysics' determining our present intellectual world we need to rethink the problem of being and this means recovering the problem as it had been experienced in the original, 'first', beginning.

(4) eg Martin Heidegger: Hölderlin's hymns. "Germania" and "The Rhine", translated by William McNeill and Julia Ireland, Indiana University Press, 2014, p.112 (in the Kindle version): 'In all of this, that understanding of beyng that gained power at the commencement of Western philosophy - and in the meantime has, in genuine and non-genuine variations, dominated German thought and knowing, particularly since Meister Eckhart - lies near and is once again powerful. It is the conception of being that we find in a thinker with whom Hölderlin knew himself to have an affinity: Heraclitus.'

That might serve, not so much as a bird's eye view of Heidegger's thinking but more like Heidegger as seen from the moon. However, since we are talking about the political implications of his thought we have to confront the embarrassing fact that when the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, Heidegger, who already had connections with Conservative circles in Germany, joined the Nazi Party. At the same time he became Rector of the University of Freiburg and for a year he showed every sign of being an enthusiastic Nazi reformer. He clearly thought he could exercise an influence on Nazi thinking but he soon realised that he couldn't. He resigned as Rector and more or less retired from public life. But he continued to lecture and write and it was in this period - the 1930s - that he did what many people, myself included, consider his most important work.

The literature on the subject of Heidegger's engagement of the Nazis is huge but for the moment I will content myself with a comment by a friend of mine, John Minahane, the person who first persuaded me that Heidegger was worth getting to know. After quoting the Irish commentator Fintan O'Toole calling Heidegger a 'thoroughgoing Nazi', Minahane continues:

'a thoroughgoing Nazi who was not a racist and who contemptuously rejected biological racism again and again. A thoroughgoing Nazi who could write at length about Bolshevism, and repeatedly, without once mentioning Jews! (This dog that did not bark in the night was not noticed not barking by the decontaminators; but then, they were not listening very closely.) A thoroughgoing Nazi who believed that Nazism was not, as it claimed to be, a solution to the modem political crisis, but merely that crisis in a more advanced stage; who thought that the Nazis were doing more damage to the German rural communities than any politicians before them; who regarded the war on Russia as an act of folly and a disaster; who believed that the great event most of all to be desired was a dynamic spiritual interaction between Germany and Russia. - Quite some thoroughgoing Nazi!' (5)

(5) John Minahane: 'An Invitation to think', Heidegger Review, No 1, July 2014, p.6.

Because of his engagement with the Nazis, he was for a while prevented from lecturing after the war. What might appear rather surprising is that his reputation as a major philosopher was restored after the war largely by the French existentialists whose political sympathies were generally left wing - most obviously Jean Paul Sartre, whose book Being and nothingness obviously follows on from Heidegger's Being and time.

However what concerns us here is Heidegger's reception in Iran and Russia and since in Iran we are dealing with supporters of the Iranian revolution and in Russia we are dealing with Alexander Dugin, himself often dismissed as a Fascist and eminence grise behind the currently very unpopular Vladimir Putin, you may feel I'm putting Heidegger back into the sinister category.