1905 - WAR AND REVOLUTION

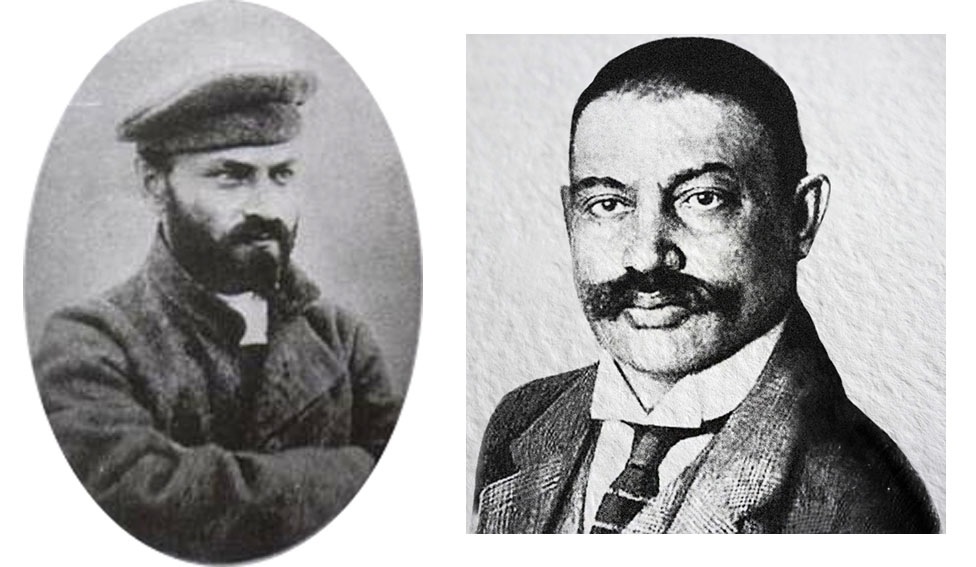

Grigori Gershuni Yevno Azef

There was a large increase in Jewish emigration to the US in the years 1904 and 1905. Solzhenitsyn attributes this not to Kishinev or Gomel but to the desire to avoid conscription in the Russo-Japanese war, which began in February 1904 (NS) with the surprise Japanese attack on Port Arthur in China which had been leased to Russia as the only port on the Pacific that the Russians could use all the year round. The war turned on rivalry between the two powers for influence in China and Korea. He quotes the Jewish Encyclopaedia saying that the proportion of Jews in 1902 was 30 and for 1903, 34 for every Christian evading conscription. But he also quotes the Encyclopaedia saying that during the war there were between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews serving together with 3,000 Jewish doctors and that both the generally anti-semitic journal Novoe Vremia and General Denikin paid tribute to the quality of their service (Solzhenitsyn, pp.386-7). Nonetheless the Japanese military effort, and eventual spectacular victory, were rendered possible by a huge loan - $200 million - from the American Jewish banker Jacon Schiff. Schiff also used his very considerable influence to prevent any American loans going to Tsarist Russia. Assuming that his intention was to improve the conditions of Jews in Russia it doesn't strike me as a good way of going about it.

In his account of the 1905 revolution and the events surrounding it, Solzhenitsyn lays great stress on the role of the Jews, in this case acting in support of the general revolutionary cause rather than a specifically Jewish interest. Notable examples include Grigori Gershuni and Mikhail Gots, who feature among the founders of the Social Revolutionary Party. Gershuni in particular was active, together with Mikhail's brother Abram Gots, in the Party's 'Combat Organisation', responsible for a number of important assassinations including, in 1904, Vyacheslav von Plehve, accused of being behind the Kishinev pogrom, and in 1905, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich who, as Governor of Moscow had been responsible for the mass expulsion of Jewish artisans in 1901. (4) Gershuni was arrested in 1904 and replaced as head of the Combat organisation by Yevno Azef, also Jewish, later revealed as having been a police informer and agent provocateur.

(4) After the assassination, his wife Elizabeth - like her sister the Tsarina Alexandra, a grand daughter of Queen Victoria - became a nun and founded an order which, unusually for Orthodox monks and nuns, was devoted to good works among the poor. She was killed by the Cheka in 1918 and is recognised by the Orthodox Church as a saint and martyr.

Frankel (whose concern is mainly with specifically Jewish politics rather than Jews involved in general revolutionary politics) mentions Gershuni in passing as one of an array of revolutionaries who visited the Jewish community in New York in 1906 raising money for a variety of causes. He quotes the Jewish Socialist leader Moyshe Baranov, writing in January 1906:

'Never has one danced in the Russian colony in New York as during this last year. One danced for the Bund; one danced for the free-thinking Socialist-Revolutionaries; and one even danced for the scientific Social Democrats. One danced for the Jewish widows and orphans in Odessa, for the revolutionary sailors in Sebastopol, for the Latvian socialists and the Polish socialists ... The more they went on strike and went hungry in Europe, the more one danced in New York. The more the shooting over there, the more the quadrilles danced over here.' (5)

(5) Jonathan Frankel: Prophecy and politics - Socialism, Nationalism and the Russian Jews, 1862-1917, Cambridge University Press, 1984 (first published 1981), p.492.

In particular, Solzhenitsyn (p.396) draws attention to the interesting case of Pinchas/Pyotr Rutenberg.

The starting point for the 1905 revolution is generally seen as 'Bloody Sunday' on the 9th (20th) January, when troops fired into a crowd of workers and peasants advancing on the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. The crowd was led by an Orthodox priest, Father Georgiy Gapon, and was carrying icons and portraits of the Tsar. It was, in appearance at least, anything but revolutionary.

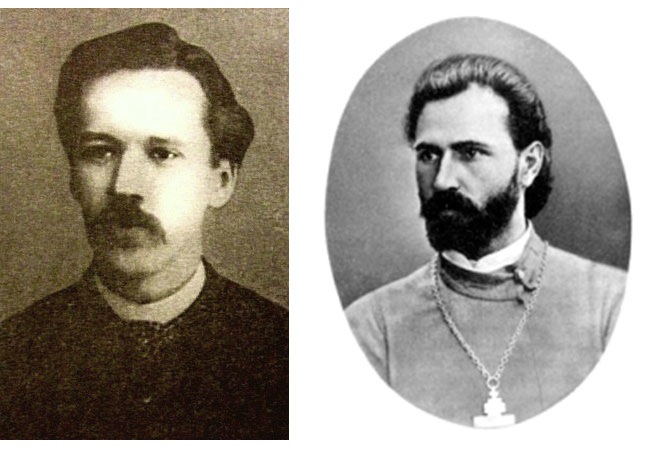

Sergey Vasilievich Zubatov Georgy Apollonovich Gapon

Gapon had been the founder in 1904 of the 'Assembly of Russian Factory and Plant Workers.' This was one of the 'police unions' set up following an initiative of S.V.Zubatov, Chief of the Moscow Okhrana (political police), with the intention of emphasising purely economic rather than political demands. Zubatov had been appointed head of the whole Okhrana in August 1902 but was dismissed by the Interior Minister, Plehve, after the contradictions between the police and the police union were drawn to breaking point by a general strike in Odessa in 1903. However, Plehve continued to experiment with officially recognised unions. To give the account by Richard Pipes:

'One of the post- Zubatov unions which he authorised was led by a priest, Father George Gapon. The son of a Ukrainian peasant, Gapon was a charismatic figure who genuinely identified with the workers and their grievances. He was inspired by Leo Tolstoy and agreed to cooperate with the authorities only after considerable hesitation. With the blessing of the governor-general of the capital, I. A. Fullon, he founded the Assembly of Russian Factory and Plant Workers to work for the moral and cultural uplifting of the working class. (He stressed religion rather than economic issues and admitted only Christians.) Plehve approved Gapon’s union in February 1904. It enjoyed great popularity and opened branches in different quarters of the city: toward the end of 1904, it was said to have 11,000 members and 8,000 associates, which overshadowed the St. Petersburg Social-Democratic organisation, numerically insignificant to begin with and composed almost entirely of students. The police watched Gapon’s activities with mixed feelings, for as his organisation prospered he displayed worrisome signs of independence, to the point of attempting, without authorisation, to open branches in Moscow and Kiev. It is difficult to tell what was on Gapon’s mind, but there is no reason to regard him as a “police agent” in the ordinary meaning of the term - that is, a man who betrayed associates for money -because he indubitably sympathised with his workers and identified with their aspirations. Unlike the ordinary agent provocateur, he also did not conceal his connections with the authorities: Governor Fullon openly participated in some of his functions. Indeed, by late 1904 it was difficult to tell whether the police were using Gapon or Gapon the police, for by that time he had become the most outstanding labor leader in Russia.' (6)

(6) Richard Pipes: The Russian Revolution, 1899-1919, Fontana Press, 1992 (first published 1990), p.22.

The period prior to 1905 saw intense activity on the part of the 'Union of Liberation' whose main activity in Russia consisted of a series of 'banquets' in which toasts were proposed demanding constitutional reform, following the example of the revolutionaries in France (and Britain) in the late eighteenth century. This was the movement that later in 1905 gave birth to the Constitutional Democratic Party - the 'Cadets'. Dismissed by the Social Democrats as 'bourgeois', its leading theorist, Peter Struve, had previously been responsible for the first programme of the Russian Social Democratic movement and the Liberation movement was closely allied with the Social Revolutionaries. If we follow Pipes's account it was this movement that provided the main political impetus through most of the events of 1905.

It also attracted the support of many Jews. Quoting Solzhenitsyn (pp.387-8) 'Like all the Russian liberals they showed themselves to be "defeatists" during the war with Japan. Like them they applauded the "execution" of the ministers Bogolepov, Sipiagin, Plehve.' It was in this context that the 'Society for the attainment of full civil rights for the Jewish people' was formed and its demands became a central feature of the Cadet platform.

Pipes quotes Gapon's own account of his involvement with the Liberation Movement:

'Meanwhile, the great conference of the Zemstvos took place in November, and was followed by the petition of Russian barristers for a grant of law and liberty. I could not but feel that the day when freedom would be wrested from the hands of our old oppressors would be near, and at the same time I was terribly afraid that, for lack of support on the side of the masses, the effort might fail. I had a meeting with several intellectual Liberals, and asked their opinion as to what the workmen could do to help the liberation movement. They advised me that we also should draft a petition and present it to the Government. But I did not think that such a petition would be of much value unless it were accompanied by a large industrial strike.'

Pipes continues:

'Gapon's testimony leaves no doubt that the worker petition that led to Bloody Sunday was conceived by his advisers from the Liberation Movement as part of the campaign of banquets and professional gatherings. At the end of November, Gapon agreed to introduce into his Assembly the resolutions of the Zemstvo Congress and to distribute to its members publications of the Union of Liberation.

'The opportunity for a major strike presented itself on December 20, 1904 with the dismissal of four workers belonging to his Assembly by Putilov, the largest industrial enterprise in the capital. Because the Putilov management had recently founded a rival union, the workers viewed the dismissals as an assault on their Assembly and went on strike. Other factories struck in sympathy. On January 7, an estimated 82,000 workers were out; the following day, their number grew to 120,000. By then, St. Petersburg was without electricity and newspapers; all public places were closed.

'Imitating the banquet campaign, Gapon on January 6 scheduled for Sunday, January 9, a worker procession to the Winter Palace to present the Tsar with a petition. As was the case with all the documents drafted by or with the assistance of the Union of Liberation, the petition generalised and politicised specific and unpolitical grievances, claiming that there could be no improvement in the condition of the workers unless the political system was radically changed. Written in a stilted language meant to imitate worker speech, it called for a Constituent Assembly and made other demands taken from the programme of the Union of Liberation. Gapon sent copies of the petition to high officials. Preparations for the demonstration went ahead despite the opposition of the socialists.' (pp.22-4)