Back to Du "Cubisme" index

Back to Cubism was born index

Previous

MONTMARTRE (and Max Jacob)

It is a good thing that this hill was celebrated by poets prior to the invention of tourism; we would never have been able to imagine what a free and charming place it was now that caravans full of imbeciles are getting it mixed up with [l'assimilent à] the Eiffel Tower or the tomb of a certain Corsican.

It is surely to these visitors and to all those who, before they can walk or think, have to keep their noses stuck to the buttocks of a guide, that the words merde engraved so many times, prophetically, in the old stones of the rue des Saules or the rue Ravignan was addressed.

I always felt the same pleasure crossing these streets every time I went from my little studio situated in the haut Lamarck to the old Bld Rochechouart to visit père Thomas, the old dealer who was interested in my paintings.

The picture business was already divided: on the one side the 'young' and on the other those who were 'known' [les 'signatures'].

Whatever became of the fifteen or twenty young painters whose canvasses were bought regularly by the père Thomas. Only one of their names has remained in my memory, that of Albert Marquet, who did not seem at the time to have anything very special about him.

A few hundred yards further on, rue Victor-Massé, Mlle Berthe Weil was more successful. She had brought together in her tiny gallery Picasso and Raoul Dufy who, in 1904, against the background of a lot of very uncertain artistic prospects, stood out clearly.

Berthe Weil! What a remarkable person she was, this ageless girl. A little piece of painted canvas was for her a substitute for all the graces, all the comforts, all the love and all the powers of the world. She never left her shop; that was where she took her meals, made up of fruits, raw in the Summer, cooked on the oven in the winter. She slept there, people said, in a cupboard. A girl who was madly in love with painting, she never spoke about it or, if she did, it was in the most laconic manner: "So-and-so exists; another, no." It was definitive - and she was rarely wrong.

Thomas fell ill and was going to give up his business, so I had to show some of my paintings to Berthe Weil. She put them against the wall, on the ground. Her little face was hardened by a supreme act of concentration. She stepped forward, stepped back, moved to the left, to the right. Several minutes had passed when she said to me simply: "All right."

I was a member of the family.

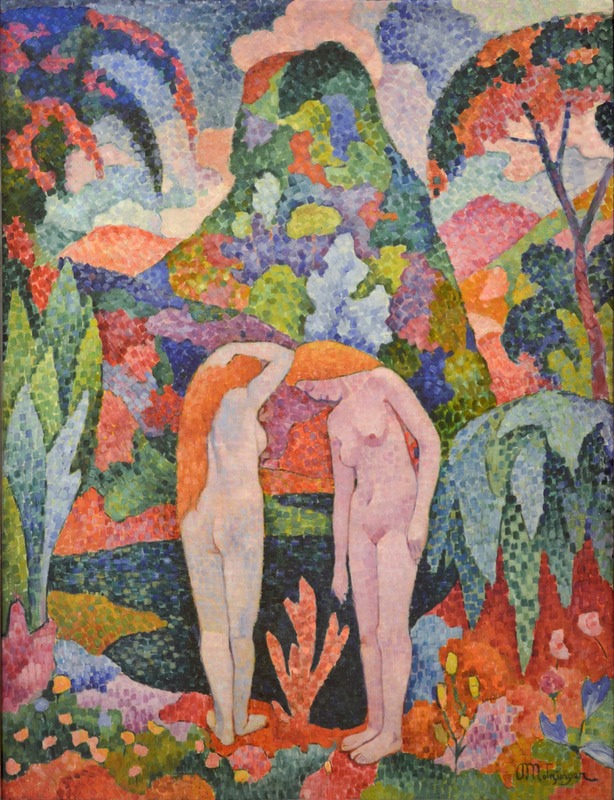

Jean Metzinger: Deux nus dans un jardin exotique, 1905

oil on canvas, 116 x 88.8 cm

Carmen Thyssen- Bornemisza collection

*

It was at her place that I met a character whose appearance had struck me several days earlier. Dressed in an immaculate overcoat around eight o'clock in the morning, he was walking down the rue Ravignan, hailing with great sweeping movements of a dazzling top hat the housewives who were taking revenge for their sorrows by furiously whipping the corpses of their carpets. In the cloud with which he was surrounded, I noted that a ceremonial pearl grey trouser leg fell upon slippers of a delicate pink, decorated with tiny embroidered blue flowers.

Max Jacob must have noticed the effort I was making not to direct my attention to his pedestrian embellishment for he immediately started to talk about it.

These slippers, given to him by his concierge, performed a useful role with regard to part of the 'system of his life'. I smiled, and he thought he had to explain further.

To make a living he practised fortune telling with cards and, when required, other sciences based on conjecture; but he was determined to exercise them honestly. One of the principles of honesty is not to present to the other as true what one knows to be false. By virtue of his work he had come to discover a truth in all popular superstitions, in the most improbable, even the most ridiculous beliefs. By getting himself into a state of complete intellectual confusion [en se mystifiant lui-même], he ceased to be an impostor and thus achieved that tranquillity in his conscience that was, for him, the greatest good. A little while later I learned that this tranquillity was not incompatible with certain acts that the morality of our time still disapproves. I went back to where I was living and he accompanied me. After having dazzled me with some judgments on contemporary painting and poetry of an astonishing lucidity, he began to show me a degree of affection which made me nervous. He took my arm, my hand, and caressed it while asking me about my love life. I had to invent a girl friend and make use of her in order to bring about a separation. He did not hold it against me. Perhaps he was even grateful to me that I had not taken advantage of him by adopting an equivocal attitude [de n'avoir point joué sur l'équivoque] so that for many long years we remained on the friendliest terms.