THE SYMBOLIST REVOLUTION

I beg your pardon for undertaking such an arid subject, and as I fear, so out-of-date: Symbolism being now "passé." This is not symbolism defined by the dictionaries as "a system of conventional signs intended to outline a dogma, a religion" but the symbolist School in fashion twenty-five years ago which, having aroused mockery and enthusiasm, has, bit-by-bit, fallen into forgetfulness. In speaking of it, I evoke the memory of a distant and already legendary era. I continue to believe that, in our theories, were incontrovertible truths the which have lost none of their applicability. Has all the fruit thereof been realised? Doubtful, that. I wish to show that, given the present state of ideas, religious art might do well to be inspired by the principles which we then proposed.

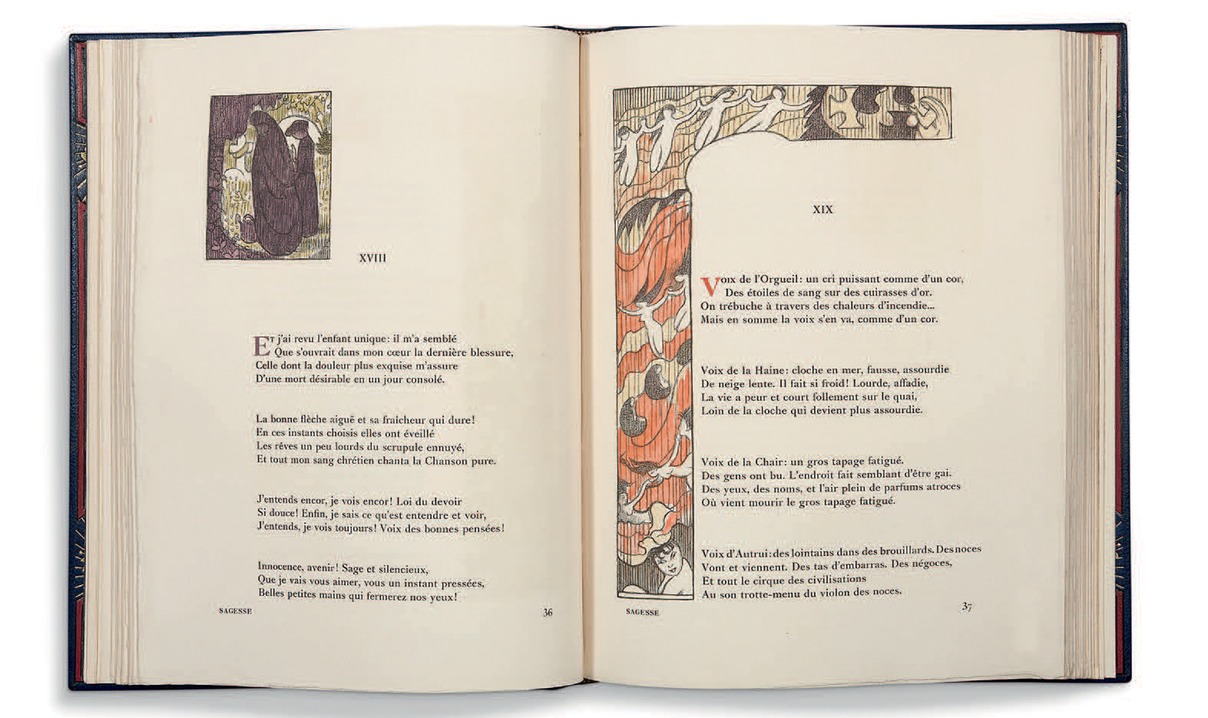

As a veteran of Symbolism, I began as a painter in the very period during which that name had been applied to new tendencies and cast upon the current parlance. I retain, faithfully enough, the memory and intellectual physiognomy of those years of my youth. With what emotion we read Verlaine’s Sagesse, which had just made its appearance. My comrade Pierre Hermant, at whose place we used to gather - Bonnard, Vuillard, Sérusier, Roussel - composed a suite of "mélodies," and I a suite of illustrations: crude images in the style of ancient woodcuts which, with Retté at my side, I showed to Mendès, Moréas, and to Verlaine himself. (1) I can still see that one on the ground floor of furnished rooms in the Rue Monsieur-le Prince; he leafs through my drawings, and pausing at one of a little communicant at the feet of the eucharistic Christ, exclaims: "That is indeed I, poor boy!"

(1) Sagesse was published in 1881.

Two pages from Verlaine's Sagesse with illustrations by Maurice Denis

I used to frequent Adolphe Retté (2), whose high-profile conversion is known to all. I had shown an Annunciation at the Salon des indépendants the which, out of fear of being thought banal, I entitled: Catholic Mystery, and Retté said: "Denis, I like your painting, I shall take it as the theme for my hashish." At the other extreme of the world of poets, I recall the serene exterior, and the quasi-liturgical gesture of Stéphan Mallarmé, leaning on his mantelpiece: "Gentlemen Whistler is within our walls..." to say that Whistler had just arrived in Paris.

(2) Adolphe Retté - 1863-1930. Poet and novelist associated both with the Symbolist and the anarchist movement. Author of Le Symbolisme, anecdotes et souvenirs, L. Vanier, Paris, 1903 and Du Diable à Dieu, histoire d'une conversion, A. Messein, Paris, 1907. He converted in 1906.

I still recall the extraordinary impression made by the first Gauguins I saw at Boussod’s, and more so those seen at the exposition of "Symbolist and Synthetist Painters," at the Champ de Mars in 1889, where there were also to be seen the curious canvasses of Émile Bernard and of Anquetin. It was the period during which Paul Fort, later Prince of Poets, directed the Théâtre d’art while Antoine, at the old Théâtre libre and Lugné-Poé at the Théâtre de l’oeuvre competed for the glory of mounting Ibsen’s plays. We sketched décors for symbolist plays, among which Maeterlinck’s L’Intruse and Pelléas were regarded as masterpieces. As to music, we were beginning to differentiate among Franck’s pupils: Chausson, Duparc, Debussy, D'Indy. Franck himself was appreciated by an élite, only. We would go hear Bordes and the Chanteurs de St.-Gervais; Sundays, we applauded Tristan and Parsifal at the Concerts Lamoureux.

All was chaotic, confused, passionate. We reacted with generosity against whatever was low, vulgar and mediocre in the schools which had immediately preceded us, against the materialism and naturalism then in favour. The names of Mallarmé, Verlaine, Maeterlinck, Laforgue, Rimbaud, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Baudelaire are indication enough of our literary preferences. In art, we liked Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Cézanne, Gauguin,Van Gogh, and also little-known impressionists; Cézanne and Degas, above all, exercised a manner of fascination upon us by virtue of the proud solitude within which they enclosed themselves.

It would seem, would it not, that the period of Sagesse, the Beatitudes and St.Geneviève should be favourable to the expression of religious sentiments. It was indeed. But it was all topsy turvy.

Our aspirations, our mysticism were not always, in truth, very orthodox. We fashioned a singular mélange of Plotinus, Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire and Schopenhauer. Little theosophical magazines abounded. Mme. Blavatsky, Péladan, Rosicrucian ideas: all were there. We also underwent the influence of German philosophy, in the end, as we had been taught in secondary school. Maurice Barrès, spiritual director of the youth of that age, and who became thereafter the motivator of French energies, was still under the sway of Hegel and Renan. There was nothing like the Revue des Jeunes, except the Société de St-Jean, to which I did not adhere until later. Founded by Fr. Clair, the society, in its beginnings, attracted painters such as Aman Jean, P. H. Flandrin, Ernest Laurent, Dulac. Our group of Gauguin disciples found moral shelter during one or two winters at the Dominican Convent in the Faubourg St-Honoré. Fr. Ollivier and later Fr. Janvier, young, but already an eloquent Thomist, taught us Christian dogma.

We also had our converts. Besides Huysmans, Charles Morice, Retté and Verlaine himself, I cite as a type of the conversions of those times that of Paul Claudel, as he recounted himself: reading the Illuminations of Rimbaud, and a true illumination, a sort of intimate miracle, perceived during a ceremony at Nôtre Dame, which gave birth to the Faith in his soul. The painter Dulac, the painter Jean Verkade, who became a Benedictine, as did the writer on art Destrée, who became Dom Destrée; Johannes Joergensen, the poet Louis de Cardonnel, they were all "intuitives," sentimentalists, poets, those whose mysterious expectations Verlaine expressed so well in the famous sonnet:

"L’Espoir luit comme un brin de paille dans l’étable..." [Hope glows as a wisp of straw in the stable..."]

The years have passed. All the superficial and amorphous in our religiosity, all that mystical "tide of passions" has become out-of-date. The Dreyfus affair divided into enemy camps all those poets, artists and thinkers who were once gathered under the same Verlaine-esque sentiment. New schools were born. Fashions changed many times. There were returns to impressionism. The decorative arts, applied arts, then in their infancy, developed greatly, extending widely. The old methods, academism, lost public favour, with the possible exception of the Catholic public. Long-abandoned techniques came into favour: tempera, fresco. The conception of painting as imitation was profoundly modified: the artist’s attitude vis-à-vis nature is no longer that which we criticised so bitterly among our elders and our professors. How did all that come about? By the effects of an evolution determined by us. That is why I must explain the theories of Symbolism in detail.