THE MANSION HOUSE INITIATIVE

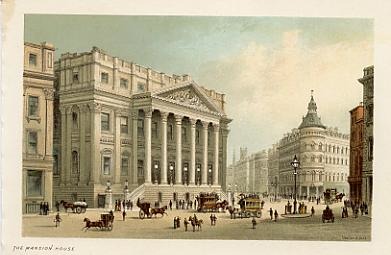

Chromolithograph of Mansion House in the 1890s

Meanwhile in England in 1880 Gladstone had become Prime Minister. There was a certain groundswell of hostility to Russia and sympathy for Jews owing to the case of L.Lewisholme, a German Jew but naturalised British citizen who had been refused permission to stay in St Petersburg on account of his Jewishness in contravention of the 1859 Anglo Russian treaty that allowed British citizens free access to Russia. Between May and August 1881, there were fourteen interventions in the House of Commons mainly from the Anglo-Jewish Conservative MP for Greenwich, Henry de Worms, but although this was the high point of the Russian pogroms the questions mainly concerned Lewisholme. (10)

(10) John Klier: Russians, Jews and the pogroms of 1881-2, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp.238-9.

British public opinion did not really start moving on the pogroms until late in 1881. A Russian Jewish Committee was established under Sir Nathaniel de Rothschild after a joint conference of the Board of Deputies and the Anglo Jewish Association. Still there was little enthusiasm for a policy of emigration, certainly not to Britain. Frankel (pp.71-2) quotes editorials in the Jewish Chronicle complaining 'that the migration of "the raw unfledged Polak", of "the swarm of Polish Jews", was the root cause of antisemitism in Rumania, in Germany (where "they vex the soul of Professor Treitschke") and indeed throughout the world.'

It seems to have been the pogrom in Warsaw in December that brought about substantial change. Two very influential articles were published in The Times in January based on the most dramatic Jewish accounts and on 1st February there was a public meeting in Mansion House (official residence of the Lord Mayor of London) condemning Russian barbarism, attended by, among many others, the Bishop of London, Cardinal Manning, Professor Bryce and Lord Shaftesbury. Frankel says that 'similar public meetings were held in the month of February in most of the major cities across the country and the British press was suddenly filled with articles condemning the pogroms.'

A committee was set up, usually chaired by the Mayor of London or by Cardinal Manning but mainly attended by prominent Jews. By mid-February, £50,000 had been raised. The policy agreed was to aid emigration to the United States but on 15th February The Times published an article by Oliphant saying that (to quote Steele) 'many of the refugees wished to settle in Palestine where - differently than in America - their religion and way of life would be safeguarded and invigorated. News of Oliphant's stance spread at once across Europe with much of the Diaspora again placing its hopes in him. Mansion House responded by drafting Oliphant into its special committee and then dispatching him as a commissioner to Galicia.'

Oliphant and his wife Alice Le Strange seem to have taken their time going to Galicia. They stayed for a fortnight in Vienna where they met Perets Smolenskin, publisher of the Hebrew language journal Ha-Shahar (The Dawn). Smolenskin had published an account of Oliphant's plan for Palestine the previous Autumn. Oliphant also won the support of the leading Polish Hebrew language journal Ha-Majad (The Preacher) which published an article by him arguing that it wouldn't be the Jews of Great Britain who would help in the colonisation of Palestine but the Protestants who 'will contribute thousands, I may well say, hundreds of thousands to promote this great object.'

The Oliphants finally arrived in Lvov, near Brody, on the 12th April 'and then immediately began their direct work with the refugees. This was when the Oliphant cult that had been swelling for several years in the Diaspora reached its zenith. He was now widely spoken of as a "saviour" and "another Cyrus" ... "In cities and small towns in Russia, Romania and Galicia" writes the historian of Zionism Nathan Gelber, "you could find in the houses of poor Jews a picture of Oliphant.' 'Oliphant committees' were formed by Jews throughout the Pale.

Parallel with the Mansion House committee a fund raising committee was established in France under the chairmanship of Victor Hugo and the Baron Alphonse de Rothschild. The French Committee and the New York Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society tried to keep to the principle observed by the Alliance Israélite Universelle of only sending a select group of able-bodied refugees and giving the rest the means to return to Russia. The Mansion House Committee however had refused to send refugees back to where they were in danger of persecution - all the greater once what could have been the start of a new wave had broken out in the majority Jewish town of Balta in March. This meant virtually unlimited emigration to the United States and the committee tried to circumvent the opposition in New York by establishing contact with Jewish committees in other US centres. 'By June 1882 three trains a week, each carrying about three hundred refugees were leaving Brody en route to the North Sea ports. All in all, from April until the end of June, the Mansion House Committee sent some 8,000 Jews at its expense to the United States. But, of course, this was not a static process. The more who were sent, the more came.'

Although the hopes placed in Oliphant contributed greatly to the influx of refugees into Brody, the Oliphants themselves only seem to have been there for less than a month. Oliphant's attention was still fixed on Palestine but Palestine was closed to the Jews by a policy of the Sultan: 'The difficulties involved forced him to issue to the Jews an appeal, together with the Alliance Israélite Universelle, that they should remain where they were for at least the next four months until such time as the Turks would allow them to settle in Palestine.'

As a result, Oliphant resigned from his Mansion House mission at the beginning of May in order to go, via Moldova and Romania, to Constantinople to argue the case directly with the Ottoman government: 'The British press presented Oliphant's journey to Istanbul as "a triumphant march."' Writing in 1887, Oliphant himself said 'so intensely wrought up were the expectations of the much suffering race who form the largest proportion of the population of this part of Europe [between Brody and Jassy, in Moldova] that at every station they were assembled in crowds with petitions to be transported to Palestine, the conviction apparently having taken possession of their minds that the time appointed for their return to the land of their ancestors had arrived, and that I was to be their Moses on the occasion.'

However the political situation had changed drastically since his earlier visit to Constantinople. In 1879 the priority of the British government had been to curtail the ambitions of Russia after its victory in the Russian-Turkish war. In 1882, however, Britain was engaged in the seizure of Egypt. In those circumstances the very reason that Jews had placed such hope in Oliphant - that he represented a substantial body of British public opinion if not actually the government - had become a pretty fatal handicap. The Turkish court was now intensely suspicious of any initiative coming from Britain. In Constantinople Oliphant tried to enlist the support of the US ambassador - without success but it's worth mentioning anyway because the ambassador in question was Lew Wallace, author of Ben Hur. (11)

(11) Oliphant did have one success. He secured the removal of Romanian Jews to Palestine, pointing out that after independence the Romanian government had refused to extend Romanian citizenship to Jews who were therefore still technically citizens of the Ottoman Empire.

Nor was Oliphant particularly supported by the British government. The public agitation which produced the Mansion House meeting obliged the Gladstone government to produce a couple of blue books on the situation in Russia but though of course condemning the pogroms and expressing sympathy for the victims they took a view similar to that of Klier and Solzhenitsyn, that accounts such as those that had appeared in The Times were greatly exaggerated and the Russian government had done what it could to control the situation. In March, in the context of the Balta pogrom, De Worms, against the wishes of the Jewish Liberal MPs, initiated a debate in Parliament, but it was without consequences. Gladstone declared (Klier, p.242) 'I am bound to believe that the Emperor of Russia and his government regard these outrages with the same feelings as we contemplate them ourselves.' The Irish MP Frank Hugh O'Donnell said that since the Jews controlled the money markets they could look after themselves, unlike the Irish or the Indians, victims of British Imperialism.

In the event, with Palestine closed to Jewish emigration and the US facing a recession and refusing to take any more, the Mansion House Committee was forced late in June to reverse its policy and press for the return of the Jews, still flooding into Brody (there were some 9,000 there in mid-July after the transportations to the US had stopped). At the beginning of June Ignatiev, suspected of anti-Jewish sentiments, was replaced by Count Dmitri Tolstoy who issued a convincingly firm circular insisting that further pogroms would not be tolerated. It was generally believed, at least among non-Jews, that the violence was at an end. On 21st June Tolstoy, at the urging of the Jewish railway magnate Samuil Poliakov (Frankel p.111), put out a further circular forbidding Jewish emigration.