WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

Is this to say that to follow such great examples, one must fall into the geometries of abstraction? I do not approve of those whose indigence of sensibility would lead them to despise nature to the profit of the constructs of their imagination. I do not preach Cubism. But it is enough for me to know that, far from limiting myself to historical painting or to the depiction of natural objects, I, the artist, a Christian, am to translate Christian sentiments by plastic equivalents. If I am well-penetrated by this theory of correspondences, I can freely vary and extend my vocabulary, enriching it with all which my sensibility gives me, there to make all within nature, and to make it speak a Christian language. (6)

(6) NOTE BY DENIS: It is by this means that Fra Angelico introduces into his work, via the "narrow gate" of Symbolism, the exquisite charm of Tuscan landscapes, the sweetness of the conventual life, grey and roseate cloisters, the freshness of feminine countenances. That art, overflowing with tenderness and mystic feeling, is nonetheless subordinated, more by intuition than by system, I think, to those same disciplines. It is that which his admirers and the makers of copies have forgotten. In Florence, they sell pale, faded things after the manner of Fra Angelico. The defect of those copies is, to return to my theory, failing to understand that the charm of Fra Angelico rests less in the object represented than in the representation itself. They wish to render them more natural. With Fra Angelico there is, on the contrary, transposition, conscious or not - and I believe not - of the elements given by sensation, in a mystic language of colours and forms, according to the tradition of his time. That virginal style, which evokes and suggests more than it narrates, is, without any doubt, Symbolism. Transformed into the style of J. Tissot, such scenes cease to be moving. A cinematographic film, representing with real figures, the Annunciation at the top of the stairs at San Marco, has made of it a scene of affliction. [The French original seems to suggest that this film has actually been made - PB]

The essential is, as I repeat, to transpose, on the plane proper to the work of art, the emotion given us by nature. That is in conformity with the exigencies of reason and of religious sentiment. That satisfies the dignity of Christian art, which cannot abide trompe-l’oeil, This places unlimited powers of suggestion in the service of Christian art.

But I see another advantage. Such an art obliges us to make a sincere effort which excludes the conventional and firstly, academism. To represent, to symbolise our emotions translating religious sentiment by plastic means, is to work in the most intimate depths of our nature, it is to take from the mysteries of internal life the clear image of our faith. Thus from the religious experience of the artist, from his personal experience, the work of art springs forth. Instead of a system of allegories of hieroglyphics - cold, banal, rigid - instead of honeyed conventions of I-know-not-what origin, of a hypocritical and sugary imagery, instead of historical painting applied to religion, the Christian artist owes us a living art, drawn from his own depths, speaking the language of his heart. To adopt such a method, to seek out correspondences among plastic signs and the modalities of his own religious sensibilities, is to institute a sort of ascesis, wherein I see the best harvest of symbolist theory. By ever-renewed means and under multiple influences of time and place, from the Catacombs until our day, Christian art, always lively, translate the essential aspirations of every era. That ascesis which places the excess of our sensibility at the service of the Faith, is that not the form of art suited to the present time? That which the best artists of yesteryear did without a system, let us do deliberately. Being in a state of crisis, among several paths, let us pick the highest. Let us take from the schools of the past as masters those who best represented the interior life.

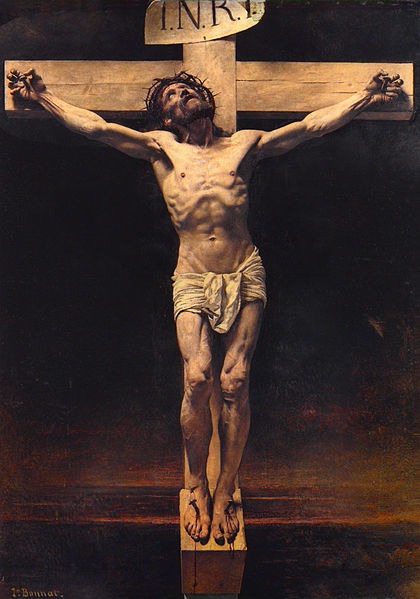

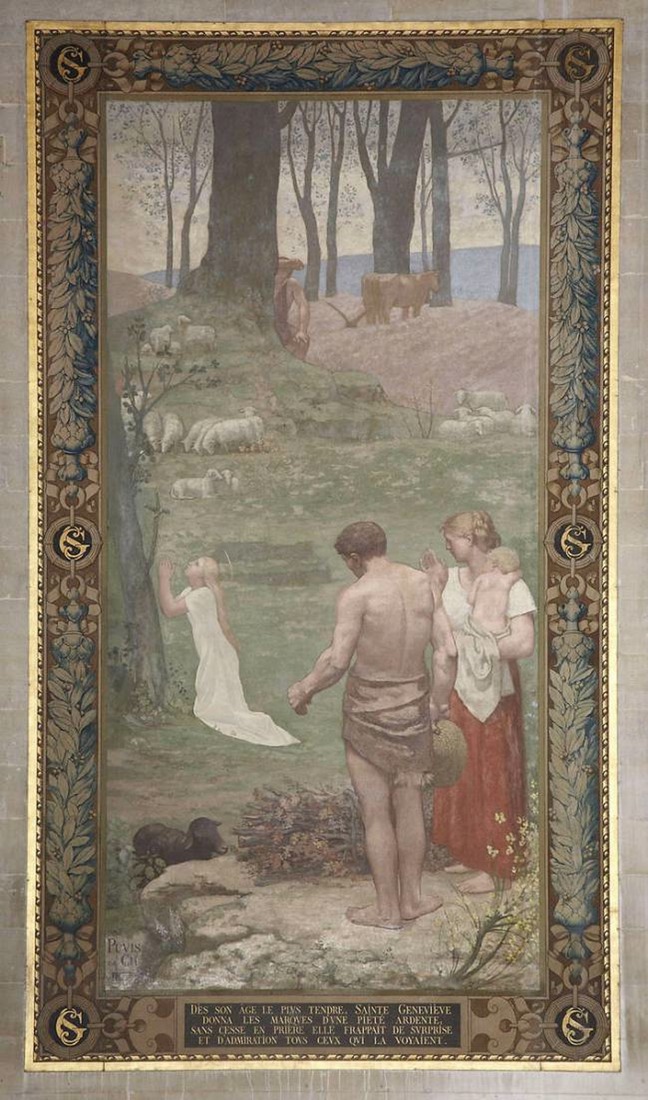

What minimally sensitive Christian nowadays hangs on his wall the Christ by Guide, or that by M. Bonnat? Who does not prefer, to nourish his piety, the little St. Geneviève in prayer by Puvis de Chavannes, or of her, watching hieratically over the sleeping city? Go to the Pantheon, attempt to pray before the Martyrdom of St. Denis. The artist’s skill is not in question: his St Vincent de Paul is a noble historical painting. Yet I defy you to experience any religious emotions before it. I know not if that would have been possible in Ribeira’s and Guerchin’s time (7). It is no longer possible.

Léon Bonnat: Christ on the Cross, 1874

(7) Seventeenth century painters based in Italy - Jusepe de Ribera - 1591 (baptised)-1652 and Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino ('squinter') - 1591-1666.

Yet at the side, there, in the sweet light of the Île-de-France, is St. Geneviève kneeling at the foot of that great tree. The simplicity, the homeliness of the gesture, the sweetness of tone, the logical yet unpredicted composition, all that constitutes a new sort of hieratism.

Having just been at the theatre, I am now before a painting. The emotion arises from the sentiment and style of that painting: a system of signs borrowed from nature familiar and clear to me. It does not tell me of an historical scene, it translates a spiritual state. "A work is born of a sort of confused emotion within which it is contained as an animal within the egg. The thought lying within that emotion I may ponder until it becomes elucidated to my eyes, appearing with all possible clarity. Thus I seek a spectacle which will translate it of a certitude. There, if you wish, is symbolism..." as Puvis de Chavannes himself said.

Freed from the confusion [fratras] of words which, I fear, have made them seem subtle and paradoxical, I place these thoughts before her high patronage. Meditate on them before St. Geneviève.

Ste Genevieve as a child in prayer, Pantheon, Paris, 1876