EPU TO COMMON MARKET

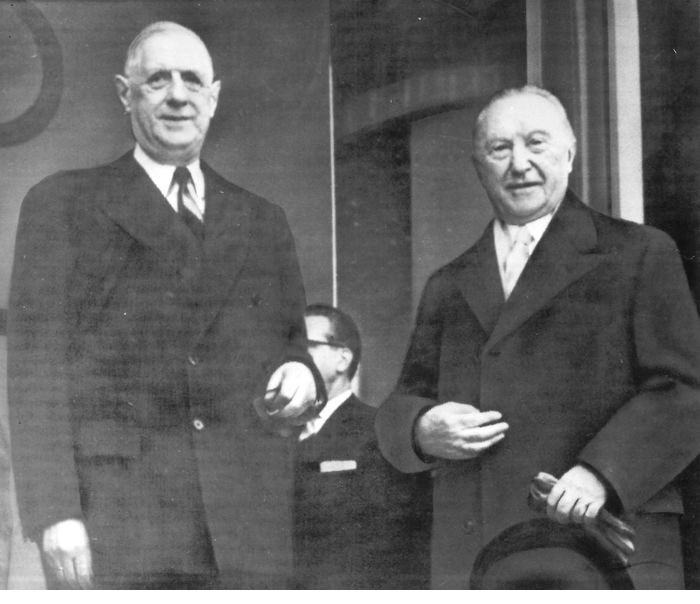

Charles De Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer in 1961

Given the apparent success of the EPU the question arises why did it come to an end? A clearing union supported by seventeen different countries seems almost too good to be true. It was of course dependent on American support and was very far removed from American ambitions, which still aimed for complete currency convertibility and the abolition of tariffs. It was accompanied by a process of trade liberalisation agreed by the OEEC. Graham Rees (European Payments Union, p.650) praises it as the means of establishing 'the financial conditions necessary for the breakdown of the trade restrictions and discrimination enshrined in the network of bilateral agreements which characterised European trade during the period of currency inconvertibility, low reserves, unreal exchange rates, inadequate production and inflationary pressures.' He concludes (p.655) that 'by this date [1958] the near convertibility of some members currencies and the increased degree of transferability of others, together with agreements concluded by most members with non-member countries for the transferability of currencies, combined to make the E.P.U. an unjustifiable survival from the years of dollar shortage.'

The accounts I have seen of the last days of the EPU mainly concern politicking between Britain and the countries that were to form the EEC but it would be interesting to know what, say, Portugal, Ireland or Turkey thought of it. The US was thinking in terms of the wider possibilities of the 37 member General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, formed in 1947 in the general world-wide perspective of the Bretton Woods arrangements. Britain was hoping in vain that sterling could join the dollar as an international reserve currency. France, which had pushed for the ECSC as a means of getting access to German coking coal, was worried about the advancing prospect of the EEC which would expose them to the full force of the revived Germany's capacity for exports. That was one reason why Guy Mollet initially welcomed the British proposal in 1956 for a free trade area that would cover the whole area of the OECC. It was when it became clear that Britain, in order to preserve the preferential arrangements it had with the Empire, wanted to exclude agriculture from its FTA, that France, embroiled in the Algerian war and experiencing severe balance of payments difficulties that went beyond what could be handled by the EPU, agreed to the Treaty of Rome, which De Gaulle in opposition regarded with scorn. (12) Nonetheless, the FTA project was going ahead under the auspices of the OECC through a committee chaired by Reginald Maudling.

(12) I am basing this account largely on Frances B.Lynch: 'De Gaulle's first veto: France, the Rueff Plan and the Free Trade Area', Contemporary European History, Vol.9, No 1 (March 2000), pp.111-135.

De Gaulle came to power in June 1958. Initially Adenauer refused to meet him owing to his reputation as a fierce nationalist and opponent of the EEC. But in Frances Lynch's account (p.123):

'The meeting with Adenauer which finally took place at Colombey-les-deux-Églises on 14 September 1958 proved to be a meeting of minds. In wide-ranging talks which covered the globe both men agreed that France and West Germany would have to co-operate closely with each other in order to make Europe independent of the United States. De Gaulle, insisting that Europe would have to be larger than the six Common Market countries, failed, however, to draw Adenauer out on the subject of the FTA. All that Adenauer would say was that Britain, whom he likened to "a rich man who had lost his fortune without yet knowing it," was not, he believed, trying to attack the Common Market in proposing the free trade area. De Gaulle, who was not as convinced that Britain's intentions were so honourable, now needed to find some means of exposing Britain's underlying strategy, but without isolating France from its Common Market partners in the process.'

Lynch (p.127) outlines the French suspicions as to Britain's underlying strategy:

'As far as the Quai d'Orsay was concerned, British objectives had become perfectly clear. The British government wanted to undermine the Treaty of Rome, but not to replace it with a larger Europe of seventeen but with the one-world system. To achieve this objective the British government had pursued a complicated strategy with, in some cases, the full support of the United States. Considering the IMF and GATT to be superior to any other treaty, aware of the divisions among the Six, and with a confidence based on the improvement of the British foreign exchange position and by the decisions taken in New Delhi to restore the convertibility of sterling and the deutschmark, the British government was trying to weaken those elements in the Treaty of Rome which had made it possible for France to open its borders. These were first and foremost the preferential aspect of the common agricultural policy which the British government was trying to get GATT to condemn; the right of West Germany to retain quantitative restrictions despite the strength of the West German balance of payments; the terms of association of the overseas territories with the EEC on the grounds that they discriminated against the interests of underdeveloped countries; and the common external tariff.'

Basically, then, De Gaulle had been opposed to the EEC on the grounds that it involved a liberalisation of its trade policy in accordance with the demands of the OEEC - convertibility of the franc, and an end to discriminatory quotas imposed on certain imports, which would 'result in grave distress for smaller French industries and even produce a number of bankruptcies' (Lynch, p.133). But he had come to accept the EEC as a means of securing at least the protections that Mollet had negotiated in the Treaty of Rome and West German support in opposition to the more dangerous FTA demanded by the British and behind that the possibility that the FTA would simply be folded into the wider system of GATT. To sustain this acceptance however, De Gaulle had to accept the austerity package proposed by the fiscal conservative, Jacques Rueff, a man who defined himself as the 'anti-keynes' and whose views on sound money and a non-interventionist economic policy were very close to those of the German ordo-liberals. We met him briefly in an earlier article in this series. (13)

(13) Peter Brooke: 'The Road to Bretton Woods: Britain goes off the Gold Standard (Part One)', Irish Foreign Affairs, Vol.14, No.1, March 2021, p.25. Also accessible at http://www.peterbrooke.org/politics-and-theology/eu-economics/part-two/

Lynch concludes:

'De Gaulle, who had been no supporter of the EEC, saw the issue as a power struggle between France and Britain over who should control the economic development of Europe, and thereby of France. At the heart of the struggle was the need to win the support of the Federal Republic of Germany. Although Adenauer shared de Gaulle's distrust of the United States he did not extend this to the United Kingdom. His basic sympathy for Britain, together with Ludwig Erhard's positive endorsement of the FTA, was to force de Gaulle to try to turn the EEC into a Franco-West German alliance in order to defeat the FTA. But not even the promise of French troops to defend Berlin against a Soviet attack, nor de Gaulle's full commitment not to employ safeguard clauses and to honour the trade liberalisation provisions of the Treaty of Rome on 1 January 1959, were enough. The West Germans would only accept the economic division of Europe provided that it was not also a monetary division ... Had de Gaulle not agreed to restore the convertibility of the franc and honour France's obligations to both the OEEC and the EEC on 1 January 1959 the consensus among the Six would have evaporated. The Rueff plan had become a political necessity.'

Not a lot to do with Schuman's professed aim of achieving regional integration as a way to prevent further wars between France and Germany.