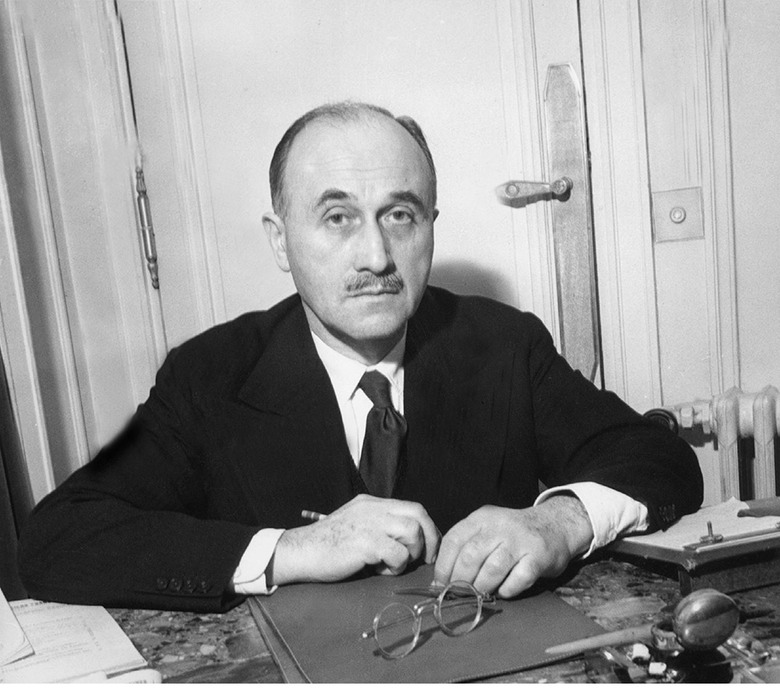

Jean Monnet

PROBLEMS FOR FRANCE

The obvious solution as far as Germany was concerned was to reinvigorate industrial production to produce exports that would generate the money necessary to purchase imports of food. The major obstacle to such a policy was France, as represented, forcefully, by Jean Monnet.

Monnet was High Commissioner of the Plan for Modernisation and Equipment, head of the 'Commissariat du plan' established by De Gaulle just before his sudden resignation as head of the French government in January 1946. He had been in England when France fell to the Germans in June 1940 but instead of joining De Gaulle or returning to France, he had gone to the United States. Roosevelt had sent him as political adviser to General Henri Giraud in Africa, whom the Americans were backing as De Gaulle's rival for the leadership of non-Communist French opposition to Hitler, but after persuading Giraud to renounce the legitimacy of the government at Vichy (thereby losing the support of Vichy supporters, who were not necessarily supporters of the German occupation) he had rallied to De Gaulle. (9) He had negotiated the Lend-lease arrangement introduced in February 1945 but abruptly terminated (together with the arrangements for the UK and USSR) with the fall of Japan in August. In December he negotiated the new loan from the US ($550 million, as against the UK's $3,750 million) and it was as part of the arrangements for this loan that the first 'Monnet Plan' appeared in March 1946.

(9) Account in Julian Jackson: France - the dark years, 1940-1944, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp.457-9.

One of the chief aims of the plan was 'to enable France to play its role in international economic competition and to become a major producer of steel thanks to massive imports of German coal.' (10) Already in October 1945, the French had proposed that the Ruhr, 'vaguely defined but embracing the whole coalfield east of the Rhine, was to be turned into an international state with its own independent government supervised by an international authority made up of France, Britain and Benelux representatives and guaranteed as a neutral and independent state by the United States and the Soviet Union. It would have its own customs barriers and its own currency ...' (11)

(10) Irwin M. Wall: 'Jean Monnet, les États-Unis et le plan français', Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire, No. 30 (Apr-Jun., 1991), pp.8-9, my translation from what I assume is a French translation of an English original.

(11) Alan S.Milward: The Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1945-51, London, Methuen, 1984, p.128.

Punitive as the Potsdam Agreement might have been, it had envisaged that Germany would, despite the division into four zones, be treated eventually as a single economic unit, thus, for example, giving the Western zones access to the agricultural produce of the Eastern Zone. France, however, had not been represented at Potsdam and did not feel bound by its conclusions. But as one of the four powers occupying Germany the French had a veto on the decisions of the Allied Control Council. Their policy was to work towards the greatest possible weakening of Germany as an economic power and therefore its division or, we might say, re-division, into many different semi-autonomous entities.

Historians have seen a speech by the US Secretary of State, James Byrnes, given in Stuttgart in September 1946 as marking the moment when the US committed to favouring Germany over the Soviet Union, and therefore as a key moment in the development of the Cold War. But at least one historian - John Gimbel - has argued that the speech was in fact mainly directed against France: 'Although cold-war historians have not generally recognised France as the object of Byrnes's Stuttgart speech, the French government and the French public did so at the time. The French press reacted most sharply and critically, and within three days of the speech, the French minister in Washington was at the State Department with the news that the French reception "had been extremely adverse," that Byrnes's promises did not satisfy France's security requirements, and that Bidault [Georges Bidault, chairman of the French Provisional government, June-December 1946] wanted to talk with Bevin and Molotov before he decided what he should do next.' (12) As a result, Byrnes 'floundered' and later, once the Soviet Union had been safely identified as the villain, tried, in his Memoirs for example, to cover his tracks. Nonetheless the situation was explained by a State Department official, John Hilldring, in October to the Meader Committee, set up to examine the corruption and inefficiency of the occupation:

'Explaining to a Meader staff member why the committee should drop its investigation of four-power relationships in Germany, Hilldring reportedly said that one of the first things the committee would learn was that the German economy was suffering mainly because the occupation authorities had shipped to France "every extra ton of coal" mined in Germany. Hilldring implied that this was being done as a result of a policy decision on the "highest levels" to restore the French economy and thus prevent the Communist party from gaining control in the French parliament.' (Gimbel, p.262).

(12) John Gimbel: 'On the Implementation of the Potsdam Agreement: An Essay on U.S. Postwar German Policy', Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 2 (June.,1972), pp.259-60.