CHRISTIAN DEMOCRACY AND THE "ECONOMIC MIRACLE"

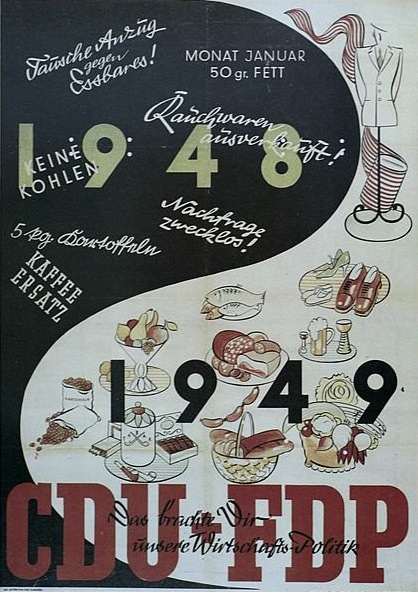

CDU/FDP poster advertising the benefits of the market in 1949 as against planning in 1948

As the 'Golden Hunger' in Germany after the war was a period of intense cultural activity so it was also a period of intense political and intellectual activity. The occupying powers in all the zones had allowed the creation of political parties, under license, from December 1945 and in the Western zones the domination of the Social Democrats (SPD), Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), together with the smaller Free Democrats (FDP), that was to last well into the twenty first century was quickly established. The contrast with the constant rearranging of party labels in France is striking.

As the Socialist SPD was a continuation of the pre-war SPD, so the Christian Democratic Union and its sister party the Bavarian Christian Social Union, were a continuation of the pre-war Centre Party which had been formed primarily to represent the interests of German Catholicism, threatened by the domination of Prussia and its Protestant monarchy. But although overwhelmingly Catholic, with its leadership very largely drawn from the old Centre Party, the CDU/CSU adopted from the start a principle of interdenominational 'Christianity', hoping to attract a Protestant membership. This, however, was problematical since the Catholic leadership tended to blame the rise of Naziism on aspects of German culture - secularisation and Prussianism - they associated with Protestantism. (11)

(11) This is discussed in eg Maria Mitchell: 'Materialism and Secularism: CDU politicians and National Socialism, 1945-1949', The Journal of Modern History, Vol.67, No.2, June 1995.

Christian Democracy has this much in common with Fascism that, unlike the Socialist SPD or the Free Market FDP, it wasn't defined by attachment to a particular economic doctrine. It therefore straddled a wide range of economic views from those close to the SPD to those close to the FDP. With the ascendancy of Konrad Adenauer and the adhesion of Ludwig Erhard, the free market view associated with Erhard and Eucken prevailed, but in the immediate aftermath of the war it was, or at least appeared to be, the left wing view that was dominant, right across the spectrum. Even the free market oriented Free Democratic Party was making proposals for an 'economic Parliament' on which both 'business' and 'labour' would have equal representation. (12) This was especially the case in the British zone where the British, engaged in nationalisation of the coal industry in Britain, were pressing for similar measures in the Ruhr, to the annoyance both of the Americans and the French. In North-Rhine Westphalia, the land (administrative division or 'state') which included the Ruhr, the CDU in February 1947, produced the 'Ahlen Programme' which called for an 'economy of a collective kind.' Abelshauser comments: 'It is on this point, on the transformation of mines and heavy metal industry into a collective property, as well as on that of the public controls of banks and credit, that the beginnings of the collaboration between the CDU and SPD - mainly in the framework of the central economic administration of the British zone - could take place.' He says that all the first constitutional texts of the lands contained clauses enabling certain major branches of industry to become collective property. 'This collective property would not necessarily replace private property, but there was a strong inclination towards a solution of a collective order for mines, energy, metalworks and steelworks.' (13) In other words, the 'cartels'.

(12) Prowe: Economic Democracy, pp.466-7.

(13) Werner Abelshauser: 'Les nationalisations n'auront pas lieu. La controverse sur l'instauration d'un nouvel ordre économique et social dans les zones occidentales de l'Allemagne de 1945 à 1949'. Le Mouvement social, No.134, Jan-March, 1986, pp.81-96. This extract, pp.91-2. My translation of what I assume is a French translation of a German original.

In the US zone, Abelshauser tells us, the constitutional assembly for Hesse, elected in June 1946, produced a constitution which called, with the support of the Social Democrats, Communists and 'most of the CDU' for the immediate collectivisation of 169 enterprises in mining, metalwork and transport sectors. The American administration tried to persuade them to withdraw the article and when they refused insisted that when the constitution was put to a referendum this clause should be put separately. 71.9% of Hesse electors voted in favour of collectivisation and 76.8% in favour of the constitution as a whole.

Both the British and American administrations decided, partly to avoid disputes among themselves, to delay implementation of such measures until the decisions could be made by a German administration, hoping, in the event correctly, that the mood in favour of collectivisation would have dissipated. Diethelm Prowe (Economic Democracy, pp.455-7) argues that this mood was not at all a mood of revolutionary enthusiasm. It was on the contrary a feeling that in the circumstances of the Mangelwirtschaft - scarcity economy - determined action was necessary. And that the catastrophe which had hit Germany was to be blamed on the great industrialists who had supported Hitler. At the same time there was a reluctance to see any concentration of power, especially in reaction to the experience of the Nazi wartime economy, in the hands of the state. This reluctance was felt right across the political spectrum, including in the SPD. As a result the proposed reorganisations of industry tended to be complex, attempting to bring together all the different possible interests - entrepreneurs, workers, consumers, local and national administrations. They were 'corporatist' rather than 'socialist', though the term 'corporatist', associated with Fascism, wasn't used. 'Economic democracy' was the preferred phrase.

That Erhard was Director of the Economics Administration of the Bizone has something accidental about it. When it was established, the first Director was Victor Agartz, previously head of the economic office of the British zone and one of the most committed SPD advocates of Socialist planning. But he resigned owing to ill health and was replaced by Johannes Semler of the Bavarian (formerly in the US zone) CSU. Although he was a committed free trader, under the circumstances - the shortage of raw materials, food and consumer goods - he continued the policy of price controls and rationing, together with Agartz's emphasis on the revival of heavy industry and a generally planned reorganisation of transport facilities. However, after he complained vigorously about the quality of food being supplied by the US under Marshall Aid, he was dismissed by the allied military governors in January 1948 and replaced by Erhard who, since Autumn 1947, had been a member of the Sonderstelle für Geld und Kredit (Special Bureau for Monetary and Currency Matters) of the Economics Council where, in close consultation with Eucken, he had developed 'a policy of sound money and price deregulation.'

According to Spicka, whose account I am following, the Economics Council was divided, with 44 CDU/CSU representatives against 46 Social Democrats and Communists, 'but the CDU/CSU under Konrad Adenauer wanted at all costs to avoid forming a coalition with the SPD ...

'The CDU/CSU could not agree on whom to name to the position of economics director, especially with the strong trade unionist wing of the CDU/CSU supporting more economic controls and emphasis upon heavy industry. The FDP, on the other hand, was promoting Erhard as director of the Economics Administration and its support was crucial in creating an anti-socialist bloc. As a result, in heated discussions in early March 1948, the CDU/CSU and FDP compromised by nominating the Christian Socialist Herman Pünder from Cologne to head the whole Bizone, while Erhard was nominated as the director of the Economics Administration—a position to which he was elected on 2 March 1948. As some historians have suggested, Erhard’s quick rise from obscure industrial researcher to head of the economy in the Bizone was due more to political wheeling and dealing than the CDU/CSU’s commitment to his economic ideas.' (p.38)

The result was that the currency reform was accompanied by a radical liberalisation of the economy - 90% of price controls, mainly on consumer goods, were eliminated and the remaining controls only very loosely applied - and because the reform was generally seen as a success it created a very strong bias in German politics towards the free market ideal. In particular, under Adenauer's guidance, this became the overwhelming theme of the CDU/CSU in the following 1949 election, at the expense of the party's Christian Socialist wing. The Ahlen Programme was replaced by the 'Düsseldorf Principles' (Sicka, p.61), developed in close consultation with Erhard and made public in July 1949 at the start of the CDU/CSU election campaign.

Adenauer had insisted that the theme of the campaign would be 'planned or market' - 'The system of the planned economy robs the productive man of his economic self-determination.' In Spicka's account (p.62) the Düsseldorf Principles 'did not stress the currency reform, which was an American initiative, instead arguing that the CDU/CSU economic policy led to a political-economic turning point when the efficiency of workers at all levels rose and production climbed. It was the rejection of the “ration card economy (Bezugscheinwirtschaft) that gave freedom back to the consumer.” After 20 June, “The stores became full, courage, strength, and energy were roused, and the whole nation was ripped out of its state of lethargy.”'