Back to article index

Previous

LAURENCE OLIPHANT - HIS RELIGIOUS VIEWS

In his book Land of Gilead, published in 1880 shortly before the 1881 crisis, Laurence Oliphant wrote:

'It is somewhat unfortunate that so important a political and strategical question as the future of Palestine should be inseparably connected in the public mind with a favourite religious theory ... So far as my own efforts are concerned they have no connection whatever with any popular religious theory upon any subject.' (Bar-Josef, p.33)

Well, maybe. But Oliphant had an interesting religious trajectory of his own. His parents were followers of Edward Irving, the highly respected minister of the Scottish Presbyterian church in London, friend of Coleridge and of Thomas Carlyle, who adopted a pre-millennial and restorationist position (the second coming of Christ would precede and inaugurate the thousand years of His personal rule and be accompanied by a return of the Jews to the Holy Land); but who subsequently championed the 'gift of tongues', an early moment in the development of nineteenth century Pentecostalism. An account of Irving's life was written by Margaret Oliphant, a well-known novelist of the time who also wrote a life of Laurence Oliphant. Philip Earl Steele, an American historian, specialist in Polish history, whose account will be the basis of much of what I have to say about Laurence, says that the two Oliphants weren't related but the Wikipedia account of Margaret Oliphant says that they were cousins (her maiden name was Wilson. Wikipedia says that her husband Frank Wilson Oliphant was also her cousin. I really don't feel inclined to pursue the matter any further at the present time).

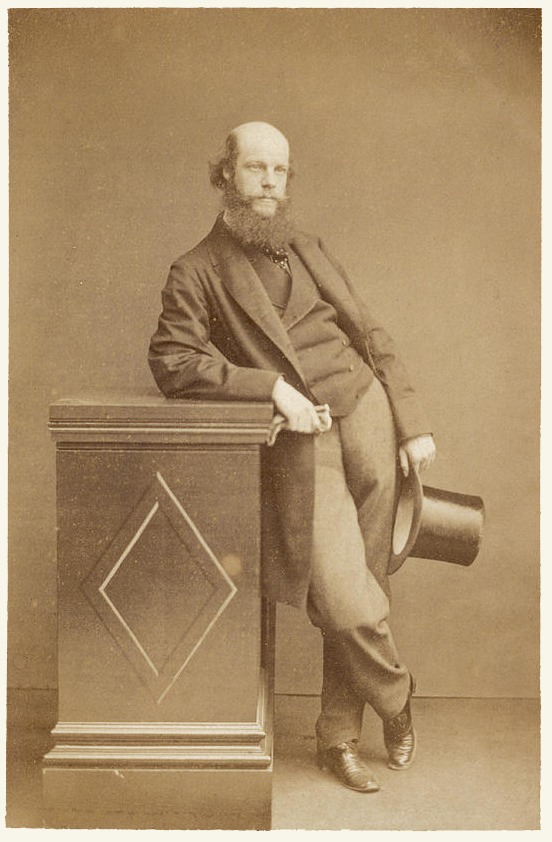

Oliphant himself was a successful diplomat, travel writer (A Journey to Katmandu, 1852; The Russian Shores of the Black Sea, 1853), satirist (Piccadilly, first published in serial form in 1865), journalist, becoming an MP in 1865. But in 1868 he threw all that up to join the spiritualist, preacher and poet Thomas Lake Harris in his 'Brotherhood of the New Life' in Brocton, New York state. I haven't established if Harris had any interest in restorationism. It seems unlikely. He wrote an interpretation of the Apocalypse, available at archive.org, which says nothing about the contemporary position of Jews or the Holy Land and is mainly concerned with a system of breathing that would characterise a new Christian humanity in harmony with the divine breath that animates the Universe. A defence of his Brotherhood of the New Life published in 1891, says:

'Conscious human life begins and ends with the fact and consciousness of breath : all men are aware of the fact that they breathe from and breathe into nature. Immersed by the continuous act of respiration in this beauteous and bounteous natural world ; they living in it ; it living in them ; their faculties open to the knowledge of Nature and their senses are thrillingly fed and solaced by its joys. With me the breath is twofold: besides the usual breathing from and into Nature, there is an organic action of breathing from and into the Adorable Fount and Spirit of existence. First realised as by a new birth of the breathing system, a breath of new intellectual and moral infancy, this, carefully held, reverently and sacredly cherished as a gift of God, has advanced till at present each organ of the frame respires in breathing rhythms, making of the body one conscious form of unified intellectual and physical harmony : the spirit, the real or higher self, is absorbing the lowly naturehood, yet meanwhile nourishing it with the rich and vital elements of a loftier realm of being. This gift that I hold is the coming inheritance of all.

Mankind awaits its New Humanity

As Earth once waited for the first-born rose.

Every act of my respiration for the last forty years has partaken of this complex character. "He breathed upon them and said, receive ye the Holy Ghost." [spiritus ; breath.] He breathes into me so that I receive the holy breath continually. In my lowly, creature emptiness and nothingness, I yet realise the organic presence of the Christ. I witness, in this age of unbelief, to the fulfilment of the Master's promise.'

He continues (and I quote this to indicate the apparently very severe discipline he imposed on Oliphant and on his wife and mother and perhaps to suggest that Oliphant's motive was genuinely charitable):

'But this mortal mind and flesh, this action and passion of the frame, can not be translated from naturehood into humanhood by any process but that of the acceptance and adoption, by each individual, of the whole corporate interest of mankind as his interest; to be embraced and served in the full denial of any superior self-interest, or family or churchly or class interest. With the discovery that he begins to breathe in God, comes to the man the discovery that God lives in the common and lowly people of the world.

'Here then is found the present cross of Christ. The aristocrat must be crucified to aristocracy ; the plebeian to plebeianism ; the luxurist to luxury ; the ascetic to asceticism ; the exclusive to exclusionism. It is a strict, honest give up and come out from spoilage, pretence and illusion. For this God is a jealous God : he proffers to man the wealth of a consummate and indestructible manhood, to be realised in each filial and fraternal personality ; but man, to receive the gift, must first accept the common burden and sorrow and service of mankind.' (7)

(7) Thomas Lake Harris: Brotherhood of the New Life - Letter from T.L.Harris with passing reference to recent criticisms, Santa Rosa, California, Founrtaingrove Library, Vol 1, No 2, July 1891, pp.4-5 and 7-8.

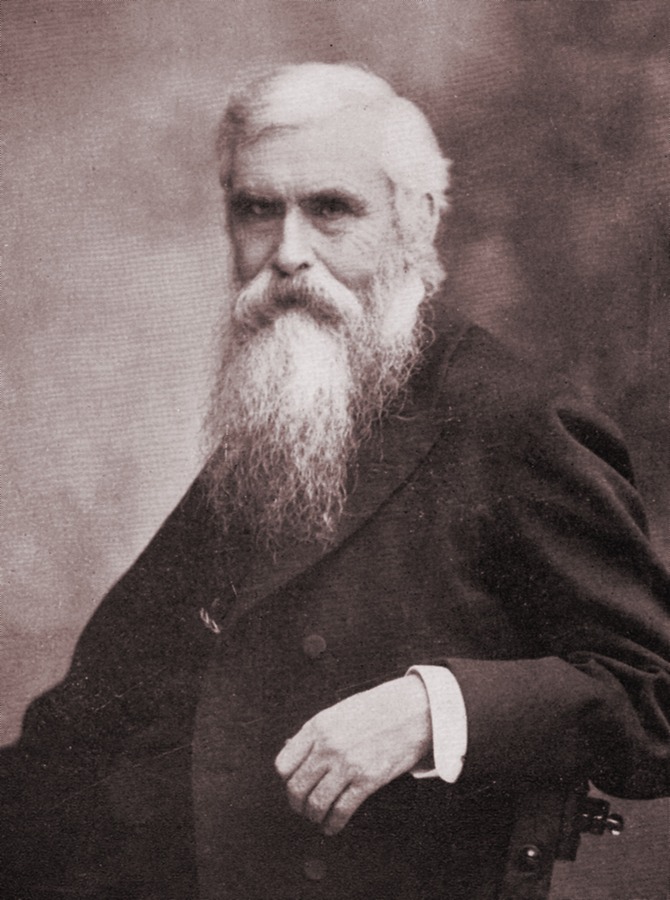

Thomas Lake Harris

He saw himself (as the title of his Apocalypse commentary - Arcana of Christianity - would suggest) as a successor to Swedenborg. We're certainly not in the usual territory of Protestant Utopianism. Both in Brocton and in his later commune in Santa Rosa, California, he developed a reputation for the production of fine wines, and the Japanese Kanaye Nagasawa, who became Harris's successor after his death in 1906, was to earn the nickname 'Wine King of California.'

Oliphant broke with Harris in 1876, launching an eventually successful law suit to regain the money he had given him. He was later (1886) to publish a novel, Massolam, based on his experience with Harris, and in fact he also seems to have continued his interest in Harris's ideas, publishing a treatise on the spiritual (and sexual) significance of breathing, Sympneumata, in 1885.(8) According to the account by Philip Earl Steele 'it was in 1978 that Oliphant began to squarely focus his attention on Palestine.' After the break with Harris 'it comes as small surprise that Oliphant, in searching for a new field of endeavour for his restless energy and feverish mysticism, turned towards the Restorationism he had been raised with. Another factor was that of the changing international situation. This particularly concerned the fears of Great Britain that, following the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Russia ... would now attempt to seize areas in the Levant from the Ottomans.'(9)

(8) There is an account in Julie Chajes: Alice and Laurence Oliphant's Divine Androgyne and "The Woman Question"', accepted for publication in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion 2015. I have it from Academia.edu. Julie Chajes teaches in the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

(9) Philip Earle Steele: 'British Christian Zionism (Part 2): The Work of Laurence Oliphant', Fathom Journal, Jan 2020, available online. Harris and Oliphant both believed that a new age was about to dawn in which humanity would be completely - and physically - transfigured. Given the connection to breath I would speculate that they had in mind something like the third age envisaged at the end of the twelfth century by Amaury of Bène - the age of the Holy Spirit (the Old Testament was the age of the Father, the New Testament of the Son). Oliphant settled in Palestine to write his own versions of Harris's ideas, together with the novel in which he criticised Harris. I think it quite possible that he might have seen the return of the Jews to Palestine as part of the process of ushering the new age in - not quite mainstream restorationism but an interesting variant.

Oliphant's 'Plan for Gilead' was, as he explained in a letter written in 1878, 'To obtain a concession in the northern and more fertile half of Palestine ... Any amount of money can be raised upon it owing to the belief which people have that they would be fulfilling prophecy and bringing on the end of the world. I don't know why they are so anxious for this latter event but it makes the commercial speculation easy ...'

He quite easily secured the support of the Prime Minster, Disraeli and of the Foreign Minister, Salisbury. Also of the novelist George Eliot, whose last novel, Daniel Deronda, published in 1876, had finished with the hero discovering that he had a Jewish mother and committing himself, without any apocalyptic motive, to the cause of a Jewish return to Palestine. With credentials from the British government he secured the support of the governor of North Palestine and a sympathetic hearing in the Sultan's court in Constantinople (according to Steele he wrote to Disraeli saying that 'In his talks with the Turks' he had 'stressed that Protestants from Great Britain and the United States would provide enormous funding to help realise the aim of establishing a Jewish colony, and he confessed to the Prime Minister that it was difficult to explain to the Turks why that was.'

Land of Gilead was published in England in December 1880. According to Steele: 'Oliphant's efforts in the Ottoman Empire and now the publication of his resulting book made him an all but universally known figure in the Jewish Diaspora, with the Jewish press extensively and most often excitedly reporting on the progress of his plans.' This included the London based Jewish Chronicle. There was of course a great difference between Oliphant's argument, based entirely on the interest of the Jews, of the Turks, and of course not neglecting the British, and the approach of the Christian Zionists organised in a society nominally at least devoted to the conversion of the Jews, or simply seeing the restoration as a necessary prelude to the return of Christ. If Oliphant had hopes of that sort he kept them carefully under wraps.