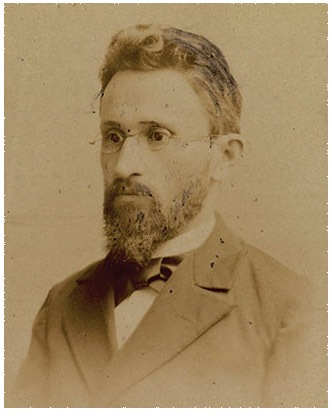

Simon Dubnow in 1896

SIMON DUBNOW AND THE JEWISH VIEW OF JEWISH HISTORY

Until 1971 and the publication of Hans Rogger's essay The Jewish policy of late tsarism it was almost universally believed that these pogroms had been fomented by the Tsarist government or by 'dark forces' close to it. This was the view forcefully put in what was long accepted as the definitive account - Simon Dubnow's History of the Jews in Poland and Russia. Dubnow was a contemporary of the events concerned and is an interesting and important figure in his own right. He was born in 1860 in the Belorussian town of Mstislavl. He was therefore raised as a teenager through the 1860s and 1870s in a period when, following the reforms of Alexander II, there was a general optimistic assumption that Russia was on the road towards a modern liberal society in which restrictions on Jews would gradually be lifted. He himself, in defiance of his family tradition, became an enthusiastic supporter of the Jewish enlightenment, the haskalah, and subsequently of the European materialist and liberal world view - Comte, Büchner, Mill, Spencer - which in Russia went under the term 'Nihilism'.

He doesn't seem to have been particularly upset by the 1881-2 pogroms at the time they occurred. Until the late 1880s, according to the account by Robert M.Seltzer, (9) 'Dubnow had maintained in his reviews and articles that the pogroms of 1881-2 were only a passing aberration. The Russian government would soon realise that it must emancipate the Jews. Russian jewry could best prepare for citizenship by undertaking a program of thorough religious and cultural reform, including the extirpation (with government's help) of Hasidic and other superstitions.' (p.292).

(9) Robert M.Seltzer: 'Coming home: The personal basis of Simon Dubnow's ideology', AJS [Association for Jewish Studies] Review, Vol.1 (1976), pp.283-301.

His views however changed radically as the 1880s progressed. In particular, following an unsuccessful effort to get permission to stay in St Petersburg:

'Late in 1886, after a two month wait in the capital to obtain bona fide legal residence there, his request was again denied and he was ordered to leave the city within twenty-four hours. He went to the nearby village of Tsarskoe-Selo, greatly perturbed. The snowdrifts among which he walked were "a symbol of frozen Russia, a lifeless country, crushed under the Tsarist regime," and "the sign of Cain, 'Jew,' follows me everywhere."'

He realised that though he had ceased to be a Jew he hadn't been accepted as a Russian. According to an entry in his diary, 1887:

'The twenty seventh year of my life was a decisive moment. Until then my thoughts still ran to general literary plans, although actually I worked only in Jewish literature. I was unhappy with this narrow sphere of activity and longed for the broader problems which my mentors Mill, Spencer, Renan and Taine studied. My eye illness, involving the danger of losing normal sight, gave me the impulse for deeper thought. I became convinced that true creativity required the process of self-limitation - that qabbalistic secret of concentration that the Infinite used to create the world from primordial chaos. I now understood that my path to the universal lay expressly through the field of the national in which I was already working. One could serve humanity only by serving one of its parts, all the more so a nation of the most ancient culture. It became clear that my general knowledge and universal ambition would give fruitful results in conjunction with the inherited treasures of Jewish knowledge and the yet unformed Jewish ideals. From this time began my propensity for the great themes of Jewish history.' (pp.293-4)

He moved to Odessa where he soon became an important part of a thriving Jewish culture, developing a philosophy which he called 'historism' (not to be confused with 'historicism'). 'A fundamental assumption of "historism" is that the goal of personal development is the realisation that one's tastes, convictions and character result from the imprint of past experience, reworked by thought and crystallised into a definite form. Therefore "a conscious relationship to the past is the criterion of personal development."' And this applies as much to peoples as to the individual: 'The essence of the Jewish national ideal is historical consciousness. Armed with the laws of Jewish historical development, the Jewish masses will be equipped to withstand the blows of fate, the sagging morale of the secular intelligentsia will revive, the national feeling of those who require a rational justification for remaining Jewish will be strengthened.' (p.295)

These ideas were worked out in a highly influential essay - What is Jewish history? -published in 1893. They provided the basis for a political argument adopted by a group calling itself the Folkspartei, formed in 1907 in St Petersburg and closely allied with the Constitutional Democratic Party, the Kadets. The argument was that the nation is a more fundamental entity than the state: 'Not atomistic citizenship in an assimilationist nation-state but legal autonomy in a culturally pluralistic, multinational state would provide the Jewish people with a recognised place in a world of nations and at the same time facilitate full Jewish participation in modern civilisation.' He was sympathetic to the Zionist idea of a distinct Jewish state but believed that it could only cater for the needs of a small part of the Jewish people. The immediate need, he told a gathering in Odessa in 1891, was not emigration to America or to Palestine but 'a propaganda tour of Europe to stir up the world against despotic Russia.'

The History of the Jews in Russia and Poland was published in an English translation in Philadelphia between 1916 and 1920. In 1917, after the February Revolution, he was given access to the Russian government archives and published several volumes concerning policy towards the Jews. I will come back to that if and when I come to the Kishinev pogrom in 1903. He was out of sympathy with the Bolshevik revolution, seeing little point in equal rights for Jews if Jews could not develop a distinct national culture. In 1922 he moved to Berlin where he wrote extensively on Jewish history and national consciousness. With the coming to power of the Nazis he moved to Riga. Following on the Nazi takeover of Latvia, according to the account in Wikipedia, he was first, at the age of 81, bundled out of his home and into the Riga ghetto and then shot as Jews in the ghetto were being rounded up for the massacre that occurred in the Rumbila forest.