Back to Form and History index

CUBISM AND ITS FULFILMENT IN 'TRADITION'

Two essays by Dom Angelico Surchamp

INTRODUCTION

Dom Angelico Surchamp died in March 2018. He was one of the last of a long line of distinguished people who had known and worked with the painter Albert Gleizes.

As a young monk in the French Benedictine Abbey of Ste Marie de la Pierre-qui-Vire, he had read and been impressed by Gleizes's essay Spiritualité, rythme, forme. His brother, Claude Jean-Nesmy (Jean Nesmy was a nom de plume used by their father, a popular novelist) had preceded him into the Abbey and, during the war, had been invited by the abbot, Fulbert Gloriès, to launch an art review, Témoignages. Prior to entering the monastery, Dom Angelico hmself (then José Surchamp) had studied with a sculptor, Henri Charlier. His adopted name - Angelico, suggested by his brother - indicates an already well-established interest in the arts and in 1946, just prior to taking his final vows, he persuaded Abbot Fulbert to let him go and study with Gleizes. 'In his [Gleizes's] eyes', he later wrote, 'it was the whole of the Benedictine Order that was coming to him!' These hopes were reflected in a letter Gleizes's pupil, the sculptor and painter Robert Pouyaud, wrote at the time after meeting Dom Angelico: 'The great Benedictine family is offering us the possibility [of an authoritative consecration] on a theological level. It is a first step, and we couldn't ask for anything better in the West. But we can hope, in the future, for a possible connection with the East. For the Pierre-qui-Vire has a foundation in Tonkin ...'

Abbey of Ste Marie de la Pierre-qui-vire, in the Morvan Forest, France

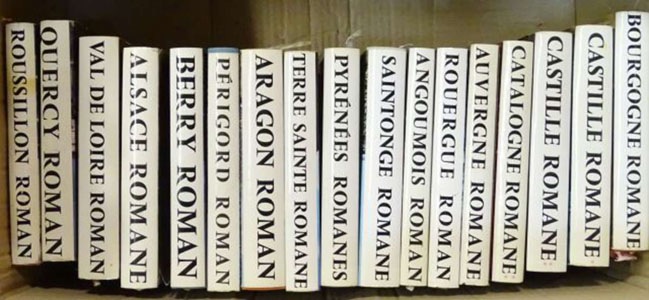

The immediate result of Dom Angelico's visit was the formation in the monastery of a workshop - the 'Atelier du Coeur-Meurtry' - devoted to producing a liturgical, mural art, supposedly on the basis of Gleizes's principles. But, promising as that was, the more substantial consequence was the emergence of Dom Angelico as a major, internationally respected, photographer specialising in Romanesque art, and the production of the very impressive 'Zodiaque' series of guides to Romanesque architecture, sculpture and painting throughout Europe, but especially in all the different regions of France (88 volumes published under the general title La Nuit du temps).

Would he have done this without the encounter with Gleizes? It is of course impossible to say but in an edition of the French review Beaux-Arts devoted to him (1), he writes: 'I owe everything to Gleizes ... fundamentally he brought me back to the Fathers of the Church, above all to Saint Augustine, and Romanesque iconography changed me completely. It was Gleizes who gave me the keys to it.'

(1) Dom Angelico Surchamp - moine et artiste, Beaux Arts/TTM éditions, Issy-les-Moulineaux, 2012

Some idea of what those 'keys' were can be had from the two essays posted here. They first appeared in Témoignages and were reproduced in the catalogue of an important retrospective exhibition of Gleizes's work held in Lyon in 1947 under the title 'Le Cubisme et son dénouement dans la tradition.' The exhibition, and Dom Angelico's articles, contributed to a major split that was occurring at the time between Gleizes and his circle on the one hand and on the other the Dominicans who were at the time promoting the use of 'modern art' in church decoration. (2) In particular the controversy turned on Gleizes's insistence that a 'sacred art' had to establish a harmonious relationship between space, time and eternity - measure. cadence, rhythm - as expressed in the analysis of the Romanesque 'Christ in Glory' in the abbey church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, given in the second of Dom Angelico's articles. In contrast the Dominican Fr Pie Raymond Régamey was demanding 'a painting that would be like a cry ...'

(2) I discuss the controversy in some detail in my book Albert Gleizes, for and against the twentieth century, Yale University Press, 2001.

These two articles provide a useful introduction to Gleizes's thinking. The first gives a brief history of his evolution from Cubism through to the essentially religious 'traditional' painting of his later years. The second outlines the actual technique of this 'traditional' painting (the essay is almost contemporary with Gleizes's own account posted on this website as Man become painter). I'm posting them in the original French but hopefully English translations will follow.