WHAT IS RELIGIOUS ART?

Ladies, Gentlemen:

The question of religious art, or of religious expression in art, is among the most ineptly posed, and therefore among the most difficult in which to come to an agreement. When it is said of a work that it is or is not religious, what precisely is being asked? I know it is a matter of feeling and that feeling has a very legitimate role in the question. But when, in fact, a critic writes, as I recently read on the matter of Gregorian music: this is prayerful, and that is not - of what value is his expressed opinion? To what may it be ascribed? Is it not strictly personal, subjective and incommunicable? It is nonetheless necessary that the intelligence should intervene, that there should be a criterion and that the question, as with all others, be considered in the light of history and of reason.

Now, should we turn our attention toward the past, it consists of an uninterrupted succession of mutually contradictory forms and aesthetics. That the Orans of the catacombs and the Christ of Byzantine mosaics; that the sculptures of the porches of Chartres; the Virgins of Fra Angelico and of Raphael; the Pilgrims at Emmaus of Rembrandt and the Ascent to Calvary of Rubens; and that Goya's Angels at San Antonio de la Florida and those of Flandrin at St. Vincent de Paul, might have been inspired by the same Christian dogma - all that is sufficient to confound the desire to impose a system, and so it becomes nearly impossible, solely in the domain of the imitative arts - which is where I wish to remain this evening - to arrive at a general definition.

If, on the other hand, we look around us, we might think we could all agree straightaway that properly religious art belongs to periods of Faith alone, and that if we should seek the perfect type, we should find it in the Middle Ages.

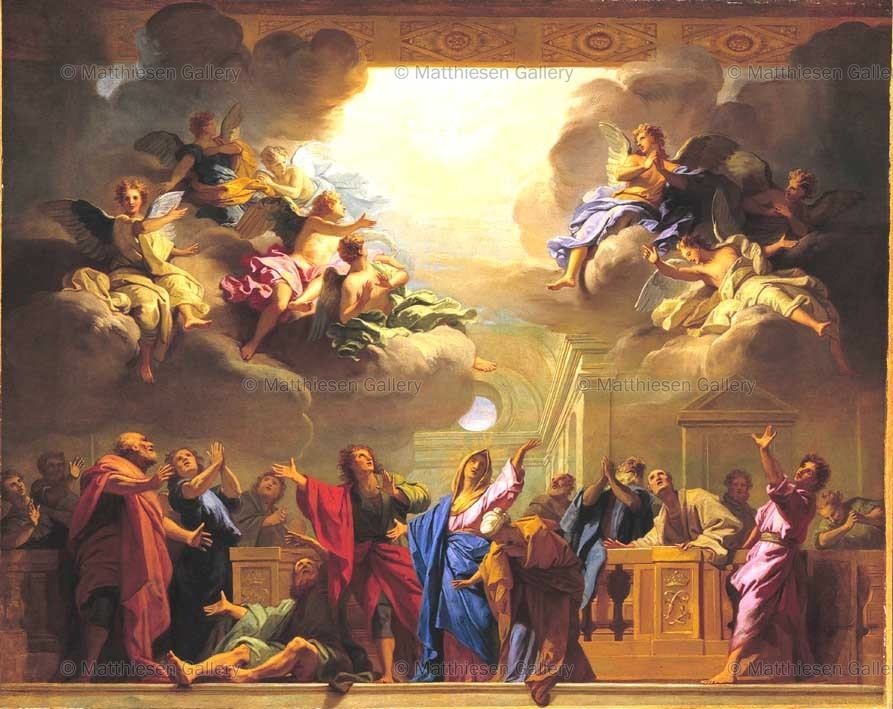

Well, that too is a matter of controversy; Louis Dimier, in a most interesting inquiry in the Revue d'Action française collected the opinions of distinguished artists and critics and demonstrated to what extent opinions on that subject are divergent. Thus it is that the painter Gaston Latouche, among others, declared that the ceiling of the chapel at the Chateau of Versailles seemed as religious, as Christian, as the vault at Assisi: and that Dimier, opposing Jouvenet (1) to Giotto, asks why "we, the French, who owe so much to the authors of the seventeenth Century, should pretend to be so horrified by the sight of the paintings which nourished their piety?"

(1) Jean Jouvenet - 1644-1717. According to the account in the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08528a.htm) he was a pioneer of a new school of French painting, influenced in particular by Rubens. In reaction to the quiet classicism of Poussin it was melodramatic and action-packed. His painting for the ceiling of the Chateau of Versailles takes the theme of the Descent of the Holy Spirit.

Jean Jouvenet: Descent of the Holy Spirit (! - PB), model for a panel of the Chapelle Royale, Versailles, c1709

That should be enough to astonish the Amis des Cathédrales. Were we to recognise how many doubtful notions and prejudices there are, on which we base our judgement on these matters, we should be much less taken by surprise.

As far as I am concerned, ladies and gentlemen, I am pleased that this controversy obliges me to what it is that makes me prefer, from a Christian standpoint, Giotto to Jouvenet, and this is why I want to explain myself before you, despite the difficulty and aridity of the subject.

I shall say things that you will find very annoying.

I beg you to arm yourselves with patience and to compensate by your attentiveness for the obscure and inadequate language which I cannot avoid using in matters of this kind.

Let us, then, put aside the opinions of those who would restrict religious art to depictions of religious subjects. For them, the differences between the sacred and the profane are exterior to art: they belong to the subject, alone. And of course it is obvious that Christian painting will comprise only Christian subjects. M.Mâle (2) has demonstrated in detail, in his abundant, ingenious, and learned iconographical studies, that Medieval Art is a vast teaching, and that the Cathedral was the Bible of the poor in the thirteenth century. He considered the methodical study of the subjects to be the necessary introduction to understanding the art of the Middle Ages. We know that the ordering of the grand theological, moral and scientific compositions which may be seen on the porches of our cathedrals was determined by the clergy. Mâle cites in detail the overall spread of certain compositions, and mocks the naïve affirmations of Victor Hugo who could in all seriousness write: "There exists a privilege for the expression of thought in stone in the Middle Ages, comparable to our freedom of the press: the liberty of Architecture. That liberty goes very far. Sometimes a portal, a façade, a whole church possesses a symbolic meaning quite different from that of the liturgy, or even frankly hostile to the Church."

(2) Emil Mâle - 1862-1954. Best known as author of L'Art religieux du XIIIe siècle en France. Étude sur l'iconographie du Moyen Âge et sur ses sources d'inspiration (Armand Colin, Paris, 1898, published in an English translation in 1913). Gleizes's La Forme et l'histoire has a chapter criticising him (especially his later - 1922 - account of art in the twelfth century) for exaggerating the importance of the figurative aspect of the works.

Such churches, hostile to the Church, such compositions in revolt against dogma, have never existed. In truth no more following the Renaissance than before it. The theologians who dictated to Tiepolo the schema of the ceiling of S.Maria del Rosario in the Gesuati of Venice [1737-39 - PB], or the compositions by Fr. Pozzi at S. Ignazio in Rome (3), were neither less knowledgable nor less orthodox than those who drew up the schema for the "Cappellone degli Spagnoli" (Sta. Maria Novella, Florence) [1365-7 - PB] or the layout of the "Bible of Amiens." (4)

(3) The chapel of St Ignatius in Rome has frescoes by Andrea Pozzo, and by Stefano Pozzi, both eighteenth century. Andrea was a Jesuit lay brother which could account for Denis's 'Fr' - for frater.

(4) Name given by Ruskin to the facade of the thirteenth century Cathédrale de Notre Dame in Amiens.

The value of the theological argument of these paintings tells us nothing of the value of the religious sentiment expressed. It is not enough to have a good religious subject to make a good religious painting, any more than would be the case for profane subjects.

Of course, you would say! That is obvious. But you are only speaking of the exterior subject: the subject-object. But there is another subject, and that is the one the artist carries within himself, his own conviction. Theological culture has no role other than to support faith. If the artist has faith, he creates religious masterpieces. But in the Middle Ages, everyone had faith.

I'm not so sure.