THE LITERARY FALLACY

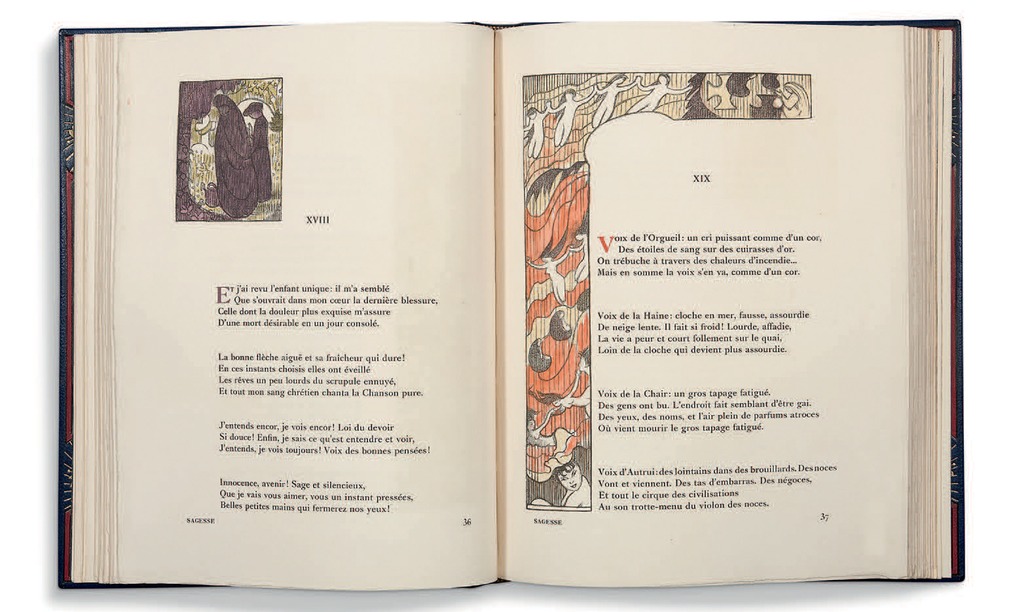

XVIII

These times are literary to the marrow: refined in minutia, thirsting for complexity. Do you believe that Botticelli, in his Primavera, wanted the sickly delicacy, the precious sentimentality which we have all seen there? Well then, work with that malevolence, that sort of notion in your head, what formulas you will derive from them!

In all decadent times, the visual arts are stripped of their leaves through literary affectations and the negations of naturalism.

XIX

To ask for calmness of mind in our present age would be asking too much. The people of the Renaissance allowed their work to spring forth, infinitely profound and aesthetic, from the abundance of their nature. A Michelangelo did not work himself up into a frenzy like a Bernini or an Annibale Carracchi, in order to seem great. His sensations, passing through the sure intelligence he had about art, achieved greatness all by themselves. It was the effort they put into their work that was the undoing of the Romantics.

XX

It is from the state of the artist’s soul that, unconsciously, or nearly so, all of the feeling in a work of art is derived: "He who would paint the things of Christ must live with Christ" said Fra Angelico. That is a truism.

Let us engage in a bit of analysis: If the vulgar herd has need of a written explanation to appreciate Puvis de Chavannes’ Hemicycle at the Sorbonne, does that mean that it is literary? Certainly not, because such an explanation is false: baccalaureat examiners may know that a given beautiful figure of an ephebe, languorously bending toward a semblance of water, symbolises studious youth. That is a beautiful form, aesthetes! Is it not? And the depth of our emotion comes from the sufficiency of those lines and colours to explain themselves as being beautiful only, and divine in their beauty.

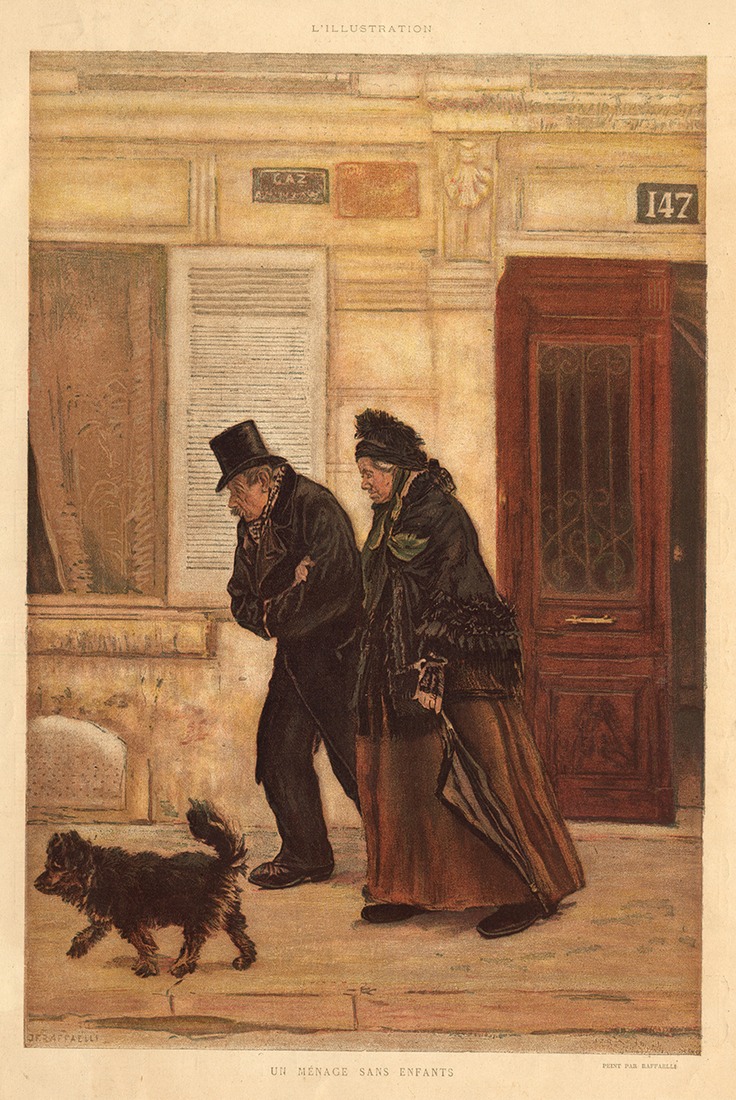

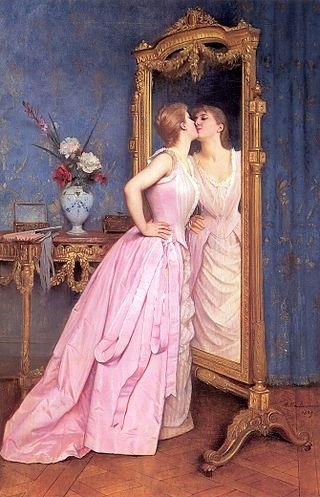

In the Ménages sans enfants (17) only the label attached to the painting is of any interest to me (the starting rate for writing such labels is 23fr 50 (18)) as I find the absurdity of a minute depiction of dirty heads and grotesque furnishings repulsive, the same unease I feel, I assure you, with M. Detaille's (19) little rifles or M. Toulmouche’s (20) bracelets.

(17) Title of a series of paintings by Raffaëlli

Ménage sans enfants, lithograph, 1885

(18) I'm assuming this is what is meant by 'on vous donnera 25 fr. 50 pour commencer'

(19) Jean-Baptiste Édouard Detaille (1848 - 1912), pupil of Meissonier, specialising, as Denis indicates, in military scenes. His painting Le Rêve shows soldiers asleep in the field with an imaginary battle raging in the clouds above them.

(20) Auguste Toulmouche (1829 - 1890) specialised in elaborately clothed Parisian women.

Auguste Toulmouche: Vanity, c1870

With Raffaëlli, effort, with Puvis de Chavannes, clear and normal play of his faculties.

But to continue. Does not the frivolity of trompe l’oeil, whether it has been merely attempted or actually achieved, contribute to that disagreeable effect which I designate as "literary?"

I imagine Paul Gauguin's Calvary as M. Friant (21) might render it. It would become Fr. Coppée (22). That is because the impression we have of a higher moral order, when confronted by that Calvary or the bas-relief Soyez Amoureuses, does not arise from the subject or from the objects in nature as depicted, but from the depiction itself, its forms and colours.

(21) Émile Friant (1863 -1932). Specialised in photographic representations of everyday life. His Entrance of the Clowns (1881) is, nonetheless, terrifying.

(22) François Coppée (1842 -1908), very popular but very sentimental poet, parodied by Rimbaud in his Album Zutique.

The emotion - bitter or consoling, "literary," as the painters say - springs forth from the canvas itself, a flat surface covered with colour, without any need to interpose the memory of another, older sensation (such as that provoked by a subject taken from nature).

A Byzantine Christ is a symbol: the modern painters’ Jesus, even if it is wearing the most correctly drawn "kiffeyeh," (23) is but literary. In the one, it is the form which is expressive, the other tries to be expressive through imitating nature.

(23) An Arabic head scarf. Denis is writing at a time when it was assumed inhabitants of the Holy Land in Jesus' day would have dressed like nineteenth century Palestinians.

And just as I have said that any representation can be called 'nature', any beautiful work can arouse the highest, most complete emotions: the Ecstasy of the Alexandrians. (24)

(24) Presumably a reference to the Neo-Platonists. In the Vie de Paul Sérusier he says Sérusier introduced him to Plotinus. This would have been shortly before he wrote the present essay.

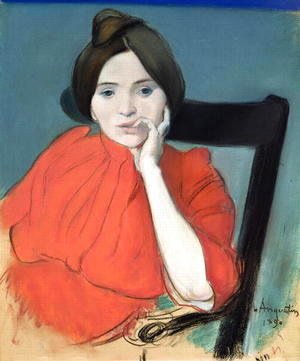

Even a simple experiment in lines, such as Anquetin’s (25) Femme en rouge (at the Champ-de-Mars), has value in its effect on our feelings.

(25) Louis Anquetin (1861-1932). Friend of Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard and Van Gogh. With Bernard developed the style known as cloisonnisme, the painting divided into clearly defined patches of bright colour. Specialised in impressions of Parisian women and night scenes, but like Bernard turned to a more archaic style, in Anquetin's case heavily influenced by Rubens.

Femme au gilet rouge, 1890

Even the frieze of the Parthenon - even, and most of all, a great sonata by Beethoven!

XXI

When the plastic arts come to close quarters with the written word, enormities appear in the book itself.

I dream of ancient missals with their rhythmic borders, the sumptuous lettering in books of antiphons, the earliest woodcuts - in sum, of something precious and delicate that could act as a complement to our own literary complexity.

But illustration - that means decoration of the book! Not:

1. placing black squares of photographic aspect on the blank spaces or in the middle of the writing

2. random naturalist cut-outs in the text

3. other, unsystematic cut-outs, pure exercises in virtuosity, sometimes (oh!) of a Japanese pretext.

To find a decoration that does not slavishly follow the text, that does not correspond exactly to the subject of the writing; but rather provides an embroidery of arabesques on the page, an accompaniment of expressive lines.

In Maurice Denis’ illustrations for Verlaine’s Sagesse one may verify the intensity of expression of the drawings where it is a matter of forms and shading - and, on the contrary, the feebleness of those into which disparate elements have been introduced by considerations of a literary nature.