THE IMPULSE TOWARDS NATURALISM

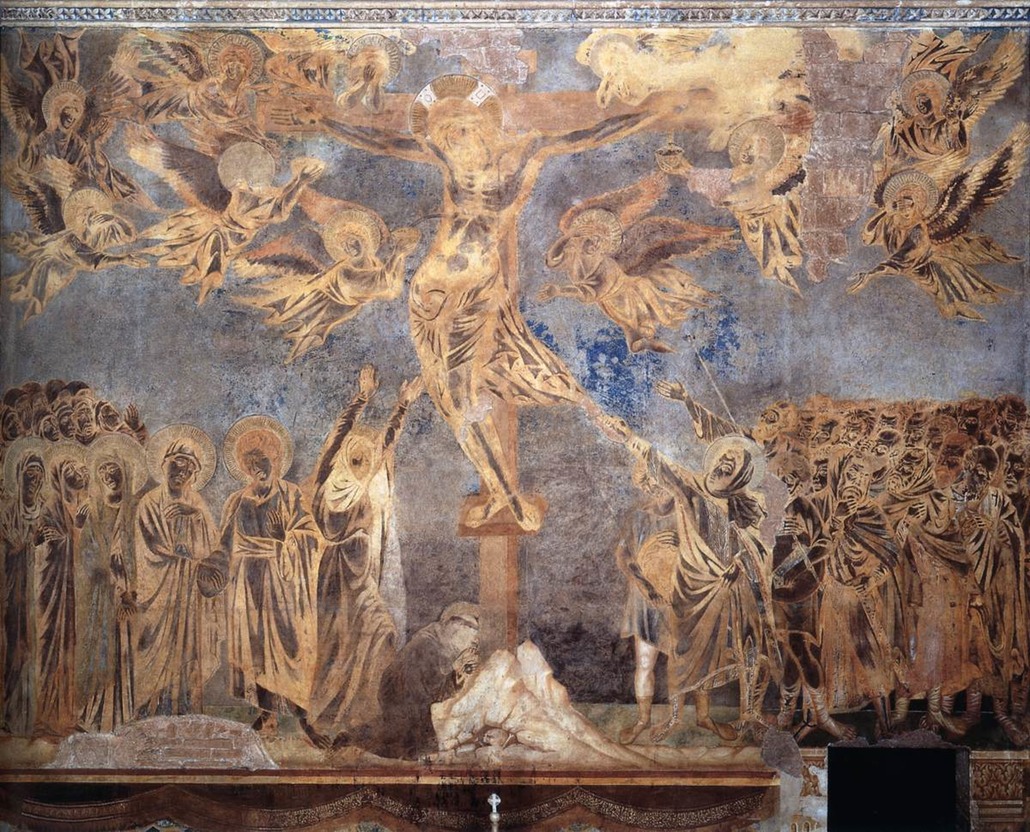

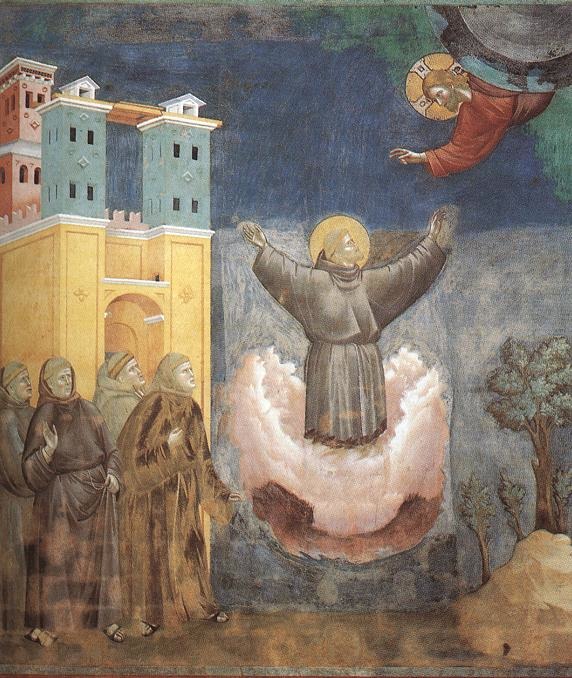

It was probably St. Francis who, in assigning so much importance to outward practices (crèches, stations of the cross, etc.), giving a more concrete charm to spirituality, rendering it more accessible to the humble, but also more practical and more suitable to contemporary life (the tertiary order) - it was probably St. Francis who led Christian painters to look for more exactitude and the illusion of life, to give verisimilitude to evangelical subjects. The charm and influence of this prodigious Giotto, one of the three or four greatest painterly minds in the history of mankind, are to be explained by the tendency among the believers of that time to give a more concrete, naturalistic expression to their faith. Those who have seen the Life of Christ by Cimabue in the upper church at Assisi, that most imposing suite of aesthetic theorems having no other goal than to demonstrate dogma, may well understand, on seeing below it Giotto’s Life of the Saint, in what direction painting and Faith were being modified in the thirteenth Century.

Crucifixion in the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi done under the direction of Cimabue, 1277-80

Ecstasy of St Francis in the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi done under the direction of Giotto, 12970-99

From that time onwards, the art of Giotto’s pupils and the whole of western painting marches forward towards the conquest of nature, just as Catholicism through various reforms, evolves in the direction of free inquiry. To the Renaissance which brought back pagan idealism, there corresponds the Reformation, whose expression in religious art is the Jesuit style, since the Jesuits with regard to the Reformation are the other side of the coin - the singular product of tired imaginations, where nothing remains of the supernatural, nor of the aesthetic: the perfect specimen of idealist decadence; the triumph of academic convention, of pathos-filled trompe-l’oeil, of a naturalism at once theatrical and pietistic.

The case of Angelico presents a mixture of an art that is, on the one hand, idealist (though not academic) and full of feeling, and, on the other, symbolist - provoking many contradictory, reasons for our admiration. Like the great painters of the Renaissance, like Rembrandt though with a lesser mastery, he has the sense of composition and of the symbol developed to such a degree that one can no longer distinguish it from the meaning of nature itself [qu'on n'en distingue plus le sens de la nature]; observation and thought, imagination and memory appear indissolubly united in his work. It is less the maturity of an art than the maturity of a man.

So full of charm, so young, so simple, he penetrated the mysteries of interior life, and restored all its poetry; he has clothed in more beautiful forms the ways in which our souls appear before God, he endowed us with a better ideal. He is the one whom we never forget, our friend in sadness, the consoler, the tutelary saint. Of Savonarola’s convent, of San Marco, he made "one of the essential places on the earth." Who would want to analyse the emotion of such a work, given that no one - not Vasari, not Taine - has been able to speak of it without turning to poetry? May he be ever blessed, loved, glorified!

He takes from Symbolism the art of his compositions, the taste for figures without a realistic shape, his draperies independent of the bodies they cover, his sumptuous backgrounds enriched with gold; the harmony of his colours is also of an incomparable purity, a true light of Paradise. At times, a conflict arises between those ever-glorious colours and the expression of lines. It is his weakness. His Descents from the Cross are pure festivals. Less of a master in such things than Giotto, Poussin or Delacroix, he could not resist the idealist and naturalist influences of his time; but he put them to work for the benefit of his blessed genius. It is from the imitation of nature that he frequently draws that touching expression, that human emotion, which is still at the present time the most seductive aspect of his work. That is how he remains accessible to the copyists of the Academy, of San Marco or the Louvre, and because of his great tenderness we forgive him for all the sentimental banalities they have painted after his work, which, however, they have made known to the world. (13)

(13) I'm interpreting ont vulgarisé in a (relatively) positive sense of 'popularised', justified I think by the d'ailleurs.

Fra Angelico: Altarpiece for the Saint Trinity Church in Florence, 1437-40, currently in the Museo di San Marco, Florence.

He is the interpreter of Compassion, of Christian purity, the poet of our sadness consoled by Christ, the painter of Mary. As Cimabue evokes the masculine beauty of dogma, the logic of a St. Paul, Angelico expresses the tender devotion of medieval saints, the compassion of a Francis of Assisi.

THE AESTHETIC OF THE RENAISSANCE

When Angelico died, Leonardo da Vinci was already born. By means of the Last Supper (1499) the aesthetic of the Renaissance was established definitively as "expression through the subject" - hence the resounding impression made by that moreover enormous work. For the first time the naturalist dream of Giotto and his successors was fully realised. To the perfection of the trompe-l’oeil was added the interest of facial expressions, the exactitude of psychological observation. At the end of the long tables of the refectory, another table, but this time, the mystical table, seems to emerge from the wall. The real architecture was extended through the devices of perspective. And one could think that those apostles and that Christ were alive, but just belonging to a nobler race, lit so naturally by the room's own windows.

Leonardo's Last Supper, 1498 in situ in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Do we have to say that if the success of the Last Supper was mostly caused by the naturalistic aspect which has been admired too much, the fact remains that Leonardo is one of the purest symbolist geniuses of the Renaissance, one of the most faithful to catholic tradition? Recall the Annunciation of the Uffizi, the St. Anne at the Louvre. Compare them with Raphael and Michelangelo, much more taken with pagan and decorative beauty.

A pleasure analogous to that which in our own day we ask of M. Munkacsy’s (14) Christs, or Tissot’s Gospel. Through that work of genius, painting entered the path of perdition. Now it is the subject, only, in a painting, which impels veneration. Christ on the Cross, whose lines the Byzantine school tortured so skilfully to achieve an aesthetically pleasing ugliness (15) - becomes the model hanging in a difficult pose, which is painful to look at, but which does not move. A very beautiful modern devotion, one that is addressed to the Love of God, the Sacred Heart, has undergone the most unfortunate depredations at the hands of the artists. Of the ardent and precious symbol, deliciously decadent, of divine Charity, they have made that insipid young man with his useless gesture, who seems to spring out of the canvas, showing us, with real hands, the horror of his genuine, bleeding innards. (16)

(14) Mihály Munkácsy (1844-1900), Hungarian painter who started with highly realistic paintings on human poverty and misery, climaxing with his dramatic Last day of a condemned man (1870) but later painted three large canvasses on the trial and crucifixion of Jesus.

Munkácsy: Ecce Homo, 1896

(15) Very difficult to make sense of Denis' original Le Christ en croix dont les Byzantins torturaient savamment les lignes pour d'esthétiques laideurs.

(16) Or as a friend of mine, a devout Catholic, remarked, an insipid young man with a strawberry on his T-shirt.