IN ARCHITECTURE

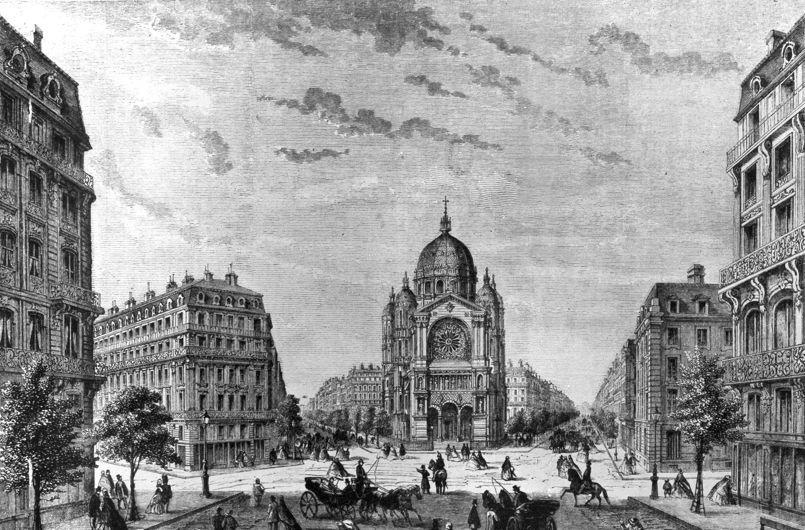

For the last twenty five years architects all over France have, for example, constructed religious buildings which testify to an activity which is often very intelligent. They are certainly not well-known. Photographs are either nonexistent or unavailable. A glorious page of the history of the French Church could be written if, going back to the Second Empire, its evolution might be followed up to our own time. Fr. Abel Favre has done so in his Pages d’art chrétien. Ever since Viollet-le-Duc’s church of St. Denis (1865), that great project of gothic renovation, more logical and better realised than Gau and Ballu’s Ste. Clotilde (1845); since Bossan’s Ste. Philomère d’Ars (1862), the first attempt at that greco-romanesque gothic style which flourished at Fourvière (1872); since Ballu’s La Trinité (1867) and Baltard’s St.-Augustin (1871), with its steel columns and imposing cupola, two churches which modernised the Renaissance type - one can say that architecture has evolved in the direction of rational construction, of decorative simplicity, of the use of new materials. Alas, we have not hesitated to instal ourselves in the left-overs of Viollet-le-Duc, moreover badly understood: we have had fake gothic, fake romanesque, fake byzantine to satiety; we have mistaken the formulas of admirable times for eternal architectural principles; and the great majority of church buildings have felt obliged to "do" the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Nevertheless, this effort to reconcile the traditions of the Middle Ages with the needs of our time, archaism with life, has given us such monuments as St. Pierre de Montrouge and the Chapel of the Rue Bizet by Vaudremer, Vaudoyer’s Notre-Dame de La Garde and the Major at Marseille; (6) Sacré-Coeur de Montmartre by Abadie, as continued by Magne. Dom Bellot’s monastic constructions, whose inspiration is so fresh and young, renew that style, and similarly M. Storez, in his chapel of Roches, has renewed, by a contrivance both ingenious and charming, the wooden Gothic vault.

(6) Cathédrale Ste Marie Majeure, often referred to as the Cathédrale de la Major.

Basilica of Saint Denis, Saint-Denis, Il-de-France. Restored from a ruined state by Viollet-le-Duc

Église Ste. Philomère d’Ars

Basilica of Notre Dame de Fourvière, Lyon, 1872-84

Église Saint Augustin, Paris

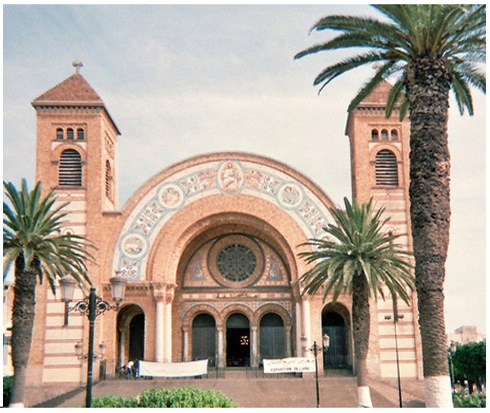

The same desire to renew the styles of the past may be noted in the works of Richardière, Chirol, Placide Thomas and M. Sainte-Marie Perrin as well as Fr.Abel Favre, responsible for the chapel on the Rue François 1er. At the same time, reinforced concrete was being used for church construction, whether using principles analogous to those of metal construction, as at St. Jean de Montmartre (A. de Baudot, 1894), or whether, by a more supple technique, dissimulating the materials utilised and instead simulating stone, as in the very original churches of M. Barbier at Bécon and Nanterre, or as at St. Paul’s of Geneva, the impeccable work of M. Guyonnet. Let us also mention works by Fr. Boubel at Jerusalem, and at the cathedral of Oran (1912), to which the Messrs. Perret contributed under the direction of Ballu, and which, by its logic, beautiful proportions and harmonious covering in ceramic tiles, is one of the most beautiful specimens of religious architecture of these last years. But it is, perhaps, the new church at Vincennes, by Messrs. Droz and Marrast, with its hanging cupola, which gives the best idea of what may be achieved by the judicious employment of reinforced and cast concrete. Cast in rigid molds, as is known, cement does not lend itself to elaborate baroque forms [des profils de carosserie] after the manner of St Jean de Montmartre, or to Gothic pastiche. It calls forth monumental forms, great classical elements, vast ceilings and vaults as in Roman basilicas or audacious cupolas as in Byzantine churches.

Église Saint-Paul, Geneva

Cathédrale du Sacré-Coeur, Oran, Algeria, 1904-13. Now converted into a public library.

Interior of Church of Saint Louis, Vincennes