HOPE FOR A POST-WAR REVIVAL OF CHRISTIAN ART

Ladies and Gentlemen

It is easy to criticise modern religious art, to show its infirmities, its poverty. That task does not frighten me. But to discern the causes of this decadence, and, even more, to propose effective ways in which it could be remedied; that is infinitely less easy. I wish to attempt this critique before you today not for the vain pleasure of self-denigration, but to derive from it some useful reflections and resolutions, and also reasons for hope. The purpose of our gathering here is to inspire a feeling of hope.

"The faith I love best," says God, "is hope."

And Péguy adds:

"'But hope," says God, "is that which astonishes me, And I cannot get over this, this little hope which seems to be nothing at all, this little daughter hope. Immortal.'" (1)

(1) Taken from Charles Péguy’s posthumously published Le Porche du mystère de la deuxième vertu.

We are here to hope together; we all believe that a renaissance of religious art is possible, and that it is even not far off. We believe that the times are favourable, and we have our reasons.

Even before it was a matter of reconstruction, before the Hun (2) came to sack and destroy our sacred buildings, in the years preceding the Great War, a renewal of decorative art was evident in our land, at the same time as a reawakening of religious sentiment. We saw this as a happy coincidence. The war did not weaken those converging activities, rather the contrary. A corresponding surge of faith and energy arose in response to the pity we felt for a France that had been invaded and devastated. Our martyred churches, charged with so many memories, victims of the barbarians, witnesses to their brutality and to our heroism, hearths of peace, concord and civilisation, shall be rebuilt. They shall be rebuilt with piety, with love and, we hope, with unanimity: I believe the public authorities will know where their duty lies.

(2) 'Boches' in the original.

Our ravaged provinces must, as in former days, be covered by a shining white garment of new churches. We have artists whose convictions and training have prepared them for this great task. There are artists who wish, like Pierre de Craon, hero of Claudel’s drama: (3)"That the new church not be an empty vessel, as a vain facade, but rather as a living organ, an engine which we put together." In order to create this organ and to assemble this engine for spreading the word and for apologetics, may those same powers of the French soul which won the war, organise the peace. It is the same qualities of lucid will, discipline, thoughtfulness and patience, the same love, that we must dedicate to the reconstruction of France - of the France that has been devastated, but also to the France of ideas [la France idéale], wounded in her intelligence, threatened in her activity and art by false doctrines, ignorance, routine and disorder.

(3) L’Annonce faite à Marie.

It is up to us to ensure that the lessons of the war are not lost. There is no more Christian art, said Proud’hon, because Christian society is no more. Christian society will have its place in tomorrow’s France, a very large place. Therefore there shall be a Christian art.

As I have already said, the tendencies before the war already corresponded to the hopes we have today. This is true of France, and true for all Europe. Without speaking of the Central Powers and of the famous Benedictine school at Beuron, we might say that Catholics and Protestants were in competition with each other. Even the Russians, with Vrubel and Roerich, (4) attempted to renew the formulas of the Orthodox Church. Wherever the decorative spirit is renewed, wherever faith burns bright, remarkable works are produced. In Joergensen’s fatherland, Denmark, the painter Skoevegaard (5) is creating one of the most interesting decorative ensembles of our age. In Holland, where conversions are numerous, Catholics at Haarlem are building a magnificent cathedral, their great innovator being the painter Jan Toorop. (6) In England, where Catholic life is intense, we may admire the new Westminster Cathedral, and we know that Burne-Jones’ influence and that of his works was not alien to the conversion of Dom Destrée. (7) And what more might I mention? Sert’s paintings in the church at Vich in Catalonia, (8) and the church of the Sagrada Familia by Gaudí, near Barcelona; in Switzerland the sumptuous glass windows of the Pole Mehoffer in Fribourg, (9) and those of Cingria in Geneva…

(4) Mikhail Vrubel - 1856-1910, best known for his paintings of impressive and mournful demons. In his Journal for 1909, during his visit to Russia, Denis comments 'Vroubel, a sort of Gustav Moreau influenced by Böcklin, is without interest'. Nicholas Roerich - 1874-1947, painter and stage designer who worked with Diaghilev. After the revolution he lived in London and was prominent in theosophical circles, taking up a lively interest in Buddhism.

Nicholas Roerich: The Last Angel, 1912

(5) Joakim Skovgaard - 1856-1933. He studied with Denis's bête noir Léon Bonnat. Denis is probably referring to his work in Vyborg cathedral (1901-1906). The Joergensen Denis mention is probably Aksel Jørgensen - 1883-1957, painter and wood engraver, specialist in scenes of urban poverty.

Viborg Cathedral, Denmark, decorated by a team under the direction of Joakim Skovgaard, 1901-1913

(6) Johannes 'Jan' Toorop - 1858-1928. Converted to Roman Catholicism in 1905. He worked in the church of St Bavo in Haarlem in 1905-6. In 1906 he became associated with De Violier, a group of Catholic artists deeply influenced by the rigorous principles of Beuron

Jan Toorop, sketch for window, 1924 in the event refused both by the Great Church of St James in the Hague and by the Utrecht (Protestant) cathedral.

(7) Dom Bruno Destrée - 1867-1919. Poet and art critic. Translated Ruskin's Lamp of Memory (from the Seven Lamps of Architecture). He became a Benedictine monk with the name Bruno (replacing Georges) in 1898.

(8) Josep Maria Sert - 1874-1945. Catalan artist, friend of Salvador Dali. His monochrome three dimensional trompe l'oeil style would seem to be very different from the sort of religious painting recommended by Denis.

(9) Józef Mehoffer - 1869-1946. Particularly known for his stained glass windows in the Gothic St Nicholas Collegiate Church in Fribourg, Switzerland. We return to Cingria later in this essay.

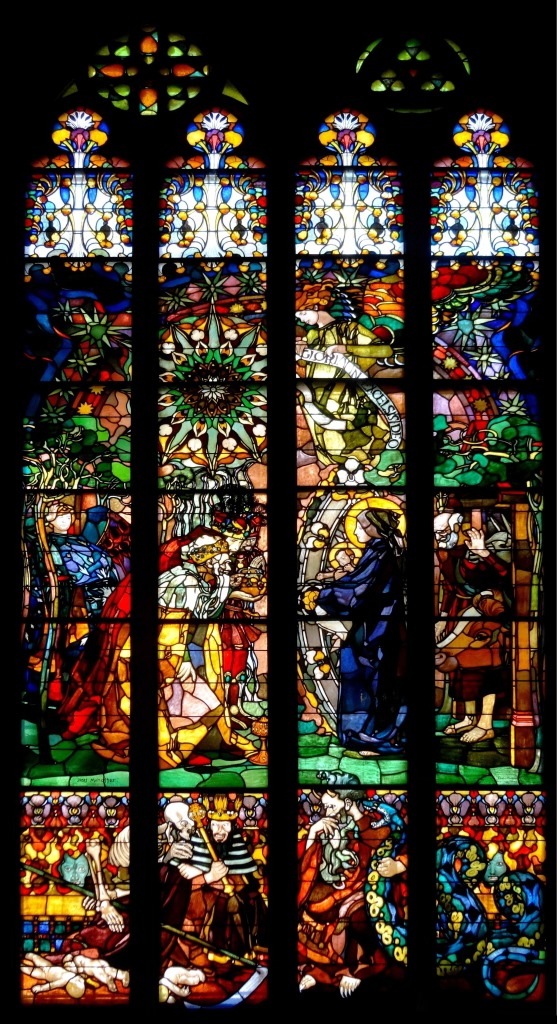

Józef Mehoffer: Window in the cathedral in Fribourg, early twentieth century (the whole project lasted some forty years, finishing in 1936).

I regret that I can only give you a dry list of names: any image, any photograph would do the job better. Most of all here in France, where we are so swift to criticise, I would like, for example, to have a collection of reproductions of religious architecture of the last twenty-five years. But to fill the gap all I can see are the necessarily succinct studies of Rev. Fr. Abel Fabre in his remarkable Pages d’Art chrétien.

In my travels across France I have at times come across new churches, chapels and convents that are interesting. Those are exceptions, alas! Still, if we compare them to the secular monuments of the period - savings institutions, town halls, schools, places of commerce - it must be agreed those are all inferior in beauty to the religious monuments. Does the city of Lyon possess anything in its civil architecture that could stand comparison with Fourvière, and is not the Sacré Coeur de Montmartre more beautiful and more original than the Grand Palais?

The Société de St. Jean, now known to everyone, has, thank God, done much since the war to stimulate the current movement. Under the leadership and happy inspiration of M. Henry Cochin, (10) it has organised a number of different competitions, for example for the reconstruction of devastated churches; but its main claim to our gratitude must be for organising the Exhibition of Christian Art in 1911 at the Pavillon de Marsan. There we could see concisely summarised all the efforts of modern religious art. As concerns France, that began with Puvis de Chavannes, and finished with Marcel Lenoir. Between those two, artists such as Mme. Lucien Simon, Besnard, Carrière, Desvallières, Paul H. Flandrin, Lameire, Lerolle, and so many others whom I can't remember, and Forain, (11) the Forain of the Pilgrims of Emmaus, all of them well represented. The only important figure missing was Botel, the distinguished Lyon painter who found favour before the normally harsh criticism of Huysmans. A similar exhibition took place the following year in Brussels. It included a considerable German contribution as well as remarkable examples of English art. The exhibitions of liturgical art held at the Pavillon de Marsan since the war have shown real progress, especially with regard to vestments, an ingenious application by feminine hands of the resources of contemporary decorative art to the traditional forms of sacred art, bringing contemporary taste into harmony with the liturgy. That is not, I think, an inconsiderable record of achievement.

(10) See note in Religious Sentiment in Medieval Art, section on 'The art of the particular'.

(11) Jean-Louis Forain (1852 - 1931), caricaturist and Impressionist painter, fiend of Manet and Degas, specialising in scenes of modern urban life, particularly a series of courtroom scenes rather reminiscent of Daumier.

If I add that in a sector of the Catholic public, shaken from its torpor by Huysmans’ invective, it has become fashionable to despise the bondieuseries of the St.Sulpice quarter in Paris; that new publications and new organisations have appeared, such as the excellent Revue bénédictine, the Vie et les Arts liturgiques, or the group L’Arche, the Ghilde Nôtre-Dame or the Amis des Arts liturgiques; if, finally, I note that, under the auspices of the powerful Revue des Jeunes an audience such as this one, numerous and sympathetic, has gathered to hear a talk on the question of modern religious art, I believe I can say that conditions are favourable; and that these augur well for a renaissance.

We should not believe, however, that the field for modern art has been won. There are terrible forces for inertia. The causes of decadence subsist. And they are not peculiar to the Catholic world, they have to do with our social conditions, our utilitarian, industrial civilisation, our education, all our false ideas and prejudices.